«“A day without laughter is a day wasted.”» Charles Chaplin

Zoetrope film strip. 20th century. 3.5 x 31.4 cm. Registry No. MFM S-28229. Museu Frederic Marès.

Jewish man from Raval, 1763. Wood carving, 40 x 80 x 30 cm. Registry No.: MR 002230. Museu de Reus.

Francesc Domingo Marqué. Five gentlemen laughing, undated. Gouache on paper, 7.5 x 15 cm. Registry No.: 1683. Museu Abelló.

Nicole Florensa. Visit by friends from Barcelona to Apel·les Fenosa's workshop on boulevard Saint-Jacques, July 1955. Photograph. Apel·les Fenosa Foundation Fund.

Antoni Batllori (Toni). Untitled, 2001. Digital print, 17.5 x 25 cm. Registry No.: ME 2744. Museu de l’Empordà. Donation by GEES (Grup d'Empordaneses i Empordanesos per la Solidaritat), 2021.

Laughter at the Museum

Curated by per Jaume Capdevila (KAP)

Humourist and caricaturist

Humour is one of the most difficult things to define, yet one of the easiest to experience. It is one of the signature traits that make us human, while combining cognitive, linguistic, psychological, and social functions with a playful form.

Laughter can be triggered by a physical stimulus (by tickling) or by an intellectual stimulus that we call humour. Humour, an inexhaustible experience that only humans enjoy (and perhaps not even all humans!), both rich and fascinating in equal measure, has various facets and functions: from inside jokes to subtle irony, from incisive satire to dark humour. From buffoonery that frees the spirit to sadistic mockery. From the jokes in ritual collective revelry to poking fun at politics and society, from intimate, cathartic, and liberating smiles to convulsive, honest, and exciting laughter. Humour permeates human existence. That is why we find representations of humour since time immemorial, and in every sphere of life.

As the custodians of the cultural, artistic, and historical legacy of our history, museums are full of works linked with certain facets of humour. Shall we find out about some of them together?

Universal and ancestral

«Man alone suffers so excruciatingly in the world that he was compelled to invent laughter.» Friedrich W. Nietzsche

Human beings’ sense of humour is our ability to perceive something as comical or funny. This capacity provokes a stimulus that can manifest physically in the form of laugher or a chuckle, but it is above all an intellectual stimulus, related with perception, with the fact of realising, of understanding, of grasping a nuance that changes the meaning of a reality, and it can happen anytime, anywhere, and under any circumstance. Human beings develop the ability to laugh during their first few months of life. Unlike the ability to cry, laughter helps guide newborns in learning and internalising all the new information that their small developing brains come across. Our laughter has an intimate and private dimension, it depends as much on our mental predisposition as on our social, cultural and intellectual history, and it also has a shared, social dimension. It is contagious and at times uncontrollable. It is also completely universal and has been present throughout the lives of human beings since time immemorial.

![[06]cap_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/06cap_2.png)

Classic bust of a young satyr, end of the 1st century-first half of the 2nd century. Marble, 30 x 26.5 x 27 cm. Registry No.: MR 008085. Museu de Reus.

![[07]buda](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/07buda.jpg)

Laughing Buddha, 19th century. Ceramic paste sculpture. Registry No.: MFM S-25556. Museu Frederic Marès.

![[08]mascara](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/08mascara.jpg)

Thai mask, 1999. Wood, 25 x 27 x 12 cm. Registry No.: 6189. Museu Abelló.

![[09]MdLl](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/09MdLl.jpg)

Corbels. Old church of Sant Joan de Lleida, 13th century. Stone sculpture. Registry No.: MLDC 477. Museu de Lleida. © Photo: Llorenç Melgosa

![[10]MdLl](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/10MdLl.jpg)

Corbels. Old church of Sant Joan de Lleida, 13th century. Stone sculpture. Registry No.: MLDC 561. Museu de Lleida. © Photo: Llorenç Melgosa

Representing a laugh

«How much lies in Laughter: the cipher-key, wherewith we decipher the whole man!” » Thomas Carlyle

Laughter is fascinating as it is a purely physical reaction to an emotional or intellectual stimulus. You can force a smile, but it is tough to fake (or to hold back) honest laughter that makes us break out into uncontrollable convulsions caused by something we find hilarious.

Laughter predates the development of language. It is a gesture that juxtaposes a biological and psychological reaction with any event we face in life. We share the ability to laugh with the great apes, so we have kept it with us throughout all our early evolutionary stages. Laughter is vital in oral-gestural communications and helps guide interpersonal relationships, making it easier to develop a sense of community.

![[11]Vidiella-cap](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/11Vidiella-cap.png)

Pere Vidiella. Smile, 20th century. Pained terracotta, 16 x 10 x 19.5 cm. MAMT NIG 3761. Museu de Tarragona.

![[12] mascara_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/12-mascara_2.png)

Anthropomorphic face mask of the Guere-Wobe people, Wé area, second half of the 20th century. Wood, 27 x 15 x 10 cm. Registry No.: 458. Museu Abelló.

![[13]v1_4](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/13v1_4.png)

Head of an angel, c. 1330. 1330. Carved stone sculpture, 11.5 x 8.7 x 7.5 cm. Santa Maria de Poblet, Tarragona. Registry No.: MFM 605. Museu Frederic Marès.

![[14]_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/14_2.png)

Virgin with Child. 14th Century. 68 x 27 x 14 cm. Registry No.: MFM 848. Museu Frederic Marès.

![[15] 1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/15-1.png)

Josep Clarà i Ayats, Childhood Joy, around 1900. Plaster, 24 x 31 x 17 cm. Registry No.: 134.631. Museu de la Garrotxa.

A serious religion... or not so much

«Humour is the instinct for taking pain playfully.»

Max Eastman

![[16]v1_3](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/16v1_3-164x300.png)

Agustí Pujol I. Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, 1587-1589. Wood carving, tempera painting, gold leaf, 127 x 55 x 43 cm. Registry No.: MR 001466. Museu de Reus.

![[17] socarrat_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/17-socarrat_1.jpg)

Religions, which strive to connect human beings with the divine through a series of practices, rituals, customs and beliefs, are all essentially serious. Every religion features a set of objects that are sacred. Through ridicule, laughter has a tremendous power to strip away the sacred. The ancient cosmogonies populated by various divinities allowed for serious and wrathful gods to co-exist with others in charge of jokes and bacchanalia. However, with monotheism, jokes became anathema to the heavens. Divine law is imposed through the fear of God… but humour drives away the fear.

Socarrat clay tile. Paterna, 15th century. Terracotta painted with manganese and iron, 44 x 36 x 3 cm. MCB 5549. Museu del Disseny.

The scriptures are thus deadly serious and Christian iconology focuses on pain, martyrdom, and suffering. Yet humour, a phenomenon that is inseparable from the human experience, ends up seeping through the cracks of orthodoxy. That is why we can find it in the margins of the books copied in scriptoria, in altarpieces, capitals, and corbels. Those who turn their back on the light are subject to ridicule, which is why the grotesque demon at the feet of Saint Bartholomew or on the altar frontal of Gia are represented as twisted and blackened characters, far removed from divine grace.

![[18]plat](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/18plat.jpg)

Decorated serving dish in green and manganese, 14th century. Museu de Manresa, MCM2196.

![[19] Iohannes_3](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/19-Iohannes_3.jpg)

Johannes. Ribagorza workshop. Altar frontal from Gia, 13th century. Tempera, stucco reliefs and rusted metal sheet remnants on wood, 100 x 146 x 8 cm. Catalogue No.: 003902-000. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Jokesters and pranksters

«People do not always realise how much truth, wisdom and seriousness were concealed under the mask of the jester»

André Gide

The Greeks used the mythical beings known as satyrs to depict the more inappropriate facets of human behaviour. The satyrs’ horns, pointed ears and goat’s hooves were appropriated a few centuries later by the little demons who played the same role in Catholicism.

With the urban development that began in the Renaissance, laughter started to be tamed. Cities were petrified of uncontrolled laughter as it could set off riots, turmoil, and subversion. Debauchery can lead to chaos, which is precisely why, manifestations of unbridled joy became modulated, limited, and ritualised.

The bard, goliard, and buffoon directed humoristic impulses in societies into professions, while humour was also channelled through the circus, theatre, comedy, music, and the grotesque figures of popular culture.

![[20] Mdll_cap](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/20-Mdll_cap.png)

Head of Silenus. White marble, 2nd century. Inv. no.: MLDC 589. Museu de Lleida.

![[21] beatus_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/21-beatus_1.jpg)

The Feast of Balthasar. Beatus de la Seu d’Urgell, 10th century. Anonymous codex. F 219, inventory no.: 501. Museu Diocesà de la Seu d’Urgell.

![[23] pla i dalmau](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/23-pla-i-dalmau.jpg)

Joaquim Pla i Dalmau. Cheap Circus, 1958. Reg. No.: 250.204. 250.204. Museu d’Art de Girona. Diputació de Girona Art Fund. Photo: Rafel Bosch.

![[22] rajoles_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/22-rajoles_2.jpg)

Anonymous. Craft tiles, 18th century, Pisa. 53.5 x 40.5 cm. Inventory No.: MEV 23914, 23916, 23918, 2643, 2641, 23913, 23917, 23912, 3174, 23919, 23920, 23915. Museu d’Art Medieval.

Collective revelry

«Anything goes in Carnival.» Refrany popular

Laughter is central in most mass celebrations around the globe and across time. Jesters, clowns, fools, dwarfs, monsters and masked individuals who host shindigs, kick off dances, make jokes, and create parodies channel the need for fun in different societies. In some festivals, transgression plays an essential role: from the Dionysian festivals and Graeco-Roman bacchanals to the now-forgotten Risus Paschalis, our Carnival, and the Jewish festival of Purim, disguises and humour serve to free people from their daily labour through costumes, inverting roles, and parody. In others, humour comes from relaxing the pressure of social norms, the effects of alcohol, and the lack of inhibition caused by collective, social fun.

Humour opens the door to liberation, offers an escape valve for the pressure of everyday life, and becomes a tool to perpetuate an established social order at the same time: disguises allow for social norms to be relaxed, a simulacrum of freedom that shuts down true calls for liberation that would put the system in danger. Festivals are a collective catharsis that act in turn as a control mechanism.

Joan Abelló. The world’s great carnival, 1979. Oil on canvas, 195 x 255 cm. Registry No.: 2041. Museu Abelló.

![[25] Lola Anglada-2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/25-Lola-Anglada-2.jpg)

Lola Anglada. Carnival. The dances , 1949. 35 x 49.5 cm. Registry No.: 9121. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer.

![[26] confetti_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/26-confetti_1.jpg)

Bag of confetti or Carnival sweets, 1916. Silk, 23 x 18 x 0.5 cm. Registry No.: MR 013725. Museu de Reus.

![[27] cartell_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/27-cartell_2-scaled.jpg)

Àlex Grifeu. Poster for the Carnival in Roses, 2001. 68 x 48 cm. MDB 1295. Museu del Disseny.

Why the long face?

«Portraits and caricatures, at the figurative level, represent opposite ends of an imaginary scale that wavers between utmost realistic figuration and the highest level of abstraction.» María Albérgamo

A caricature is a physiognomic portrait that features a distortion, whether by addition, substitution, or omission, modifying the shape of the face being represented. But we all know that in a good caricature, the greater the deformation, the greater the resemblance. In fact, the secret of a good caricature was described precisely by Ernst Gombrich, who, with his fellow colleague and Ernst (Kris), dedicated a small book in 1940 to analysing this artistic medium. In it, he states that the pleasure of seeing a caricature resides in “the theoretical discovery of the difference between likeness and equivalence”. In other words, the human brain loves discovering the most distinctive traits of the original face hidden beneath the artistic distortion.

Caricatures appeared during the Renaissance, crafted by the Carracci brothers, Bernini, and Leonardo da Vinci. The caricature was born at the same time and in the very same workshops where some of the most beautiful images in art history were created. The ritrattini carichi, or loaded portraits, were drawings that used exaggeration and deformation, along with any other recourse that enabled the artist to achieve greater expressivity. Freed from the demands of the academic canon, caricature has served to broaden the margins of artistic expressivity, and these drawings enjoyed enormous popularity on the pages of the printed press in the 19th and 20th centuries.

![[28]2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/282.png)

Francesc Soler i Rovirosa / Manuel Casagemas / Joan Ballester. Caricature album, mid-19th century. Paper and watercolour, 30 x 21 cm. Registry No.: MFM 6277. Museu Frederic Marès.

![[29] caricatura 1_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/29-caricatura-1_1.jpg)

Lluís Bagaria. Caricatura de Miquel Utrillo, 1924. Llapis sobre paper, 18,8 x 12,8 cm. Núm. de registre: 4789. Museu Abelló.

![[30] caricatura 2_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/30-caricatura-2_1.jpg)

Lluís Bagaria. Caricature of Smith, 1924. Pencil on paper, 18.8 x 12.8 cm. Registry No.: 4790. Museu Abelló.

![[33] niko_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/33-niko_2.jpg)

Nicolás Martínez Lage, “NIKO”. Francisco Franco, c. 1950. 1950. Marker on cardboard, 31.5 x 23.4 cm. MORERA Collection. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida. Donation by the Martínez Andrea Family, 1993.

![[31] bagaria_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/31-bagaria_2.jpg)

Caricature of Ramon Casas, c. 1910. 1910. Ink, watercolour and gouache on paper, 58 x 40 cm. Registry No.: 698. Museu d’Art de Sabadell.

![[32] Nonell_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/32-Nonell_2.jpg)

Isidre Nonell. En Nonell i en Pere Romeu (Nonell and Pere Romeu), c.1909. 1909. Ink and gouache on paper. Catalogue No.: 043902-D Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[34] basquiat_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/34-basquiat_2.jpg)

Jean-Michel Basquiat. Self Portrait, 1986. Acrylic painting on canvas. Registry No.: 0413. Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

Laughter against censorship

«When the tyrant can be called a tyrant, humour is no longer necessary.» Cándido

The illustrated press developed during the 19th century, together with the technical procedures that made it possible to reproduce these images. Illustration thus went from being merely a decorative complement in the turn-of-the-century publications to taking on a vital role, one that would make it easier for an image-based press to take hold.

The Charlatan. Barcelona. Year II, series 2a, No. 42 (23 December 1887). Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer. © Photo by Carles Pujades.

Others, like Josep Escobar, faced reprisal after the Spanish Civil War for the caricatures that they had published during the conflict.

Feliu Elias Apa. Crazy cow. Satirical drawing. Ink on paper. Museu de Valls.

Humour that makes you think

«Someone who makes you laugh is a comedian. Someone who makes you think and then laugh is a humourist. » George Burns

Behind every laugh brought on by a joke is a complex cognitive mechanism that has allowed the brain to establish a relationship between two elements that seemingly did not have one. Hence, when we cannot perceive this connection, we say that we don’t “get” the joke. Understanding is essential in comedy, and the profound pleasure that understanding provides has a physical manifestation, that is, a laugh. However, in order to get a joke, we have to know the code, we have to identify a context in which the joke takes on meaning.

JUMA (Josep M. Francisco). Cinderella (ashtrays), 1977. The Original Cha-Chá / Insòlit. Resin, 15.5 x 6.5 x 19 cm. Registry No.: MADB 136994. Museu del Disseny.

![[38] Josep Palau_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/38-Josep-Palau_1.jpg)

That’s why, many times we do not find something that made our grandparents laugh very funny. Along the same lines, what children laugh at often is not funny to their parents. Social, cultural, and personal contexts change, and the mechanism of the joke is completely thrown off.

Josep Palau Oller. Drawing. Published in Papitu, 1910. Palau Foundation.

![[40] hac Mor_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/40-hac-Mor_1.jpg)

Carles Hernández Mor (Carles H. Mor). The chair as a seat. Photograph, 2015. ME 2367. Museu de l’Empordà. Donation by the Associació Cultural La Muga Caula, 2015.

![[41] brossa_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/41-brossa_1.jpg)

Joan Brossa. O for “ouera” (egg basket), 1969. Wood, vinyl and iron, 35.4 x 41 x 38 cm. Registry No.: 4985. Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

An aesthetics of comedy

«People who see a drawing in the ‘New Yorker’ will think automatically that it’s funny because it is a cartoon. If they see it in a museum, they think it is artistic; and if they find it in a fortune cookie, they think it is a prediction. » Saul Steinberg

The visuals associated with comedy stray from academicism and are both simple and expressive. Synthetic doodles allow viewers to immediately grasp the situation without getting lost in the details. In fact, the lively Romanesque drawings, which originally had no comedic connotation, seen from our contemporary gaze may seem funny as they are far removed from realism. They also share expressive resources with artistic manifestations that for us are not “serious”, such as comics, funny drawings, graffiti, and children’s cartoons.

Man at prayer. Church of Sant Quirze de Pedret, 10th-11th century. Wall decoration, fresco painting, 135 x 122.5 x 5 cm. Registry No.: MDCS 1. Museu Diocesà de Solsona.

Josep Maria de Sucre. Untitled, 1964. Panel painting, 96 x 72 cm. Inv. no.: 257. 257. Museu de Granollers.

Unknown. Homily of Breda, 11th century. Museu d'Art de Girona, reg. no.: MDG0044 Bishopric of Girona Fund. Photo: Rafel Bosch.

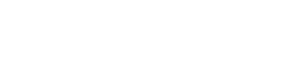

Alfred Sisquella i Oriol. Funny religious scene, undated. Ink drawing on paper, 15.4 x 21.1 cm. Museu del Cau Ferrat de Sitges. Cau Ferrat Fund, inv. no.: FM 31. © Arxiu Fotogràfic del Consorci del Patrimoni de Sitges.

The persuasion of smiling

«The secret to humour is surprise» Aristòtil

Humour boasts an important educational component: it generates involvement, draws attention, and stimulates creativity. Aware of its educational potential, humour has been used in a variety of formulas to promote diverse lessons.

![[46] L_infantil_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/46-L_infantil_1.jpg)

The first children’s magazines used funny drawings as a tool to teach and instil values in kids. Several publications, from En Patufet to TBO, as well as the more modern L’Infantil and Cavall Fort, have followed this path.

Joaquim Calderer. Quimet Trapella que tot ho esgavella. Plate for printing a page from the children’s magazine L’Infantil. Seminari de Solsona. Museu de Solsona.

![[48] nit_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/48-nit_2.jpg)

NIT (Joan Macias). The great inventions of TBO: Device to avoid the disgusting spectacle of the condemned… Ink and coloured pencil on paper, 24.9 x 34 cm. Museu de Cerdanyola.

![[49] tarja_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/49-tarja_2.jpg)

The advertising industry soon discovered humour’s potential in communications and has used it to spread the word in commercials. Some of our best cartoonists, such as Cesc, have also excelled in advertising.

Àngel Grañena. Antispasmina Cólica, 1956. Advertising card, 16.7 x 11.9 cm. GAGB 9307/14. Museu del Disseny.

![[50]cesc_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/50cesc_1.jpg)

Cesc. Book Day Poster 1977. 66.7 x 47.6 cm. Registry No.: MDB 10151. Museu del Disseny.

Political and social satire

«Satire is the most powerful weapon against the establishment. The powers that be cannot bear satire, even those governments that call themselves democratic, because laugher liberates man from his fears.» Dario Fo

Satire, a ferocious attack that uses a sharp wit, can be found in literature, music, and performing arts throughout history, seeking maximum effectiveness by reaching the widest audience possible. Starting in the 19th century, satire found a prominent space in the press, where it became a weapon of political and social struggle after becoming linked with caricatures. Deformed, defaced, and grotesque drawings of political rivals fill the pages of the satirical press. Catalonia has had a vibrant satirical press, and several generations of incisive cartoonists have created engrossing pieces. Newspaper archives hide veritable masterpieces of journalistic, critical, and incisive comedy.

Sébastien Charles Giraud. Print on the Théâtre National de l’Opéra (caricature), 1899. Engraving on paper, 54.5 x 70 cm. Registry No.: 09232. Museu Abelló.

![[52] Tomas Padró_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/52-Tomas-Padro_2.jpg)

Tomàs Padró. The Bell in Gràcia. Barcelona. Any II, Peal LX. 25 June 1871. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer. © Photo by Carles Pujades.

![[53] Opisso_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/53-Opisso_1-scaled.jpg)

Ricard Opisso. Jo hauria d’ésser aviador (I should be a pilot), 1915. Ink on paper, 31.8 x 27.9 cm. Catalogue No.: 07692 2-D. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[54] Jap_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/54-Jap_1.jpg)

Joan Antoni Poch (JAP). Untitled, 2000. Digital print. ME 2792. Museu de l’Empordà. Donation by GEES (Grup d’Empordaneses i Empordanesos per la Solidaritat), 2021.

Subversive humour

«Nothing should be taken seriously in this world; true wisdom consists of knowing how to laugh.» Zsolt Harsányi

One of the main components of humour is transgression. Intentionally comical, humoristic, or satirical drawings can transgress the norms and conventions of academic drawing and alter the way of representing reality. As such, these drawings manage to enhance the emotional effectiveness of the image and strengthen the message. While a photograph reproduces reality, drawings filter and reinterpret this reality, giving added value to the resulting image. One of the most powerful drivers of caricature is its capacity for provocation and transgression. Iconic or aesthetic transgression, or ideological provocation. Poking holes in morality, challenging power, breaking down preconceived ideas and pushing the limits of semantic or visual conventions… everything is allowed in visual satire. That’s precisely why satire has been used to address delicate and at times critical topics, such as the Spanish Civil War.

Ramon Puyol. El acaparador (The Hoarder), 1936. Lithography on paper, 68.2 x 48.3 cm. Catalogue No.: 128084-G. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[59] Maternasis_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/59-Maternasis_1-scaled.jpg)

Núria Pompeia (Núria Vilaplana i Boixons). Illustrations for the book Maternasis, 1967. Ink and collage on paper. Catalogue No.: 254647-CJT. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[56] sancho_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/56-sancho_1.jpg)

Josep Sancho Piqué. Horrors of a War, 1939. Ink on paper, 24 x 32 cm. MAMT NIG 1005 / MAMT NIG 945 / MAMT NIG 937. Museu de Tarragona.

Ramon Calsina. Tragedy. Male Violence, 1929. Pencil on paper, 67 x 50 cm. Registry No.: 5988. Museu Abelló.

Joan Brossa. Spain, 1971. Screen printing on paper, 63.8 x 44.1 cm. Registry No.: 4529. Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

Shades of humour

«Laughter is born from a jumble of unbearable pain. It is a way, both cruel and soothing, to confront the wound. » Marta Sanz

There is a curious semantic relationship between aesthetics and different types of humour, as these have been baptised with names of colours or shades that indicate important nuances.

![[60] guarda_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/60-guarda_1.jpg)

Endleaf (binding), 20th century. 22.5 x 20.67 cm. Registry No.: GAGB 906/13. Museu del Disseny.

![[61] Pilarín_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/61-Pilarin_1.jpg)

Light-hearted humour, known in Catalan as humor blanc, is the most innocent and harmless, without any kind of double entendres. Comedy meant for children is typically humor blanc (“white humour”), and authors such as Pilarín Bayés are a paradigmatic example in Catalonia.

Pilarín Bayés de Luna. The rise of the Catalan Press, 1975. Museu d’Art de Girona, reg. no.: 137.276. 137.276. Generalitat de Catalunya Fund. National Art Collection. Photo: Rafel Bosch.

![[62] smith_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/62-smith_1.jpg)

Blue comedy, coincidentally called verd (green), includes anything that has to do with sex, eroticism, and all sensual or lascivious connotations, like certain drawings by Ismael Smith.

Ismael Smith. Nano (self-portrait), 1907. Bronze cast sculpture. 40,4 x 17 x 21,4 cm. Museu de Cerdanyola. Legacy of Carles Pirozzini Martí. Catalog number: 040758-000

![[63] apa_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/63-apa_1.jpg)

On the contrary, dark humour, or humor negre, is the name for a bitter type of humour, one that is not suitable for all tastes, as it delights in the heavier aspects of existence: death, illness, pain, and suffering. It is often called unpleasant and offensive.

Feliu Elias (Apa). Provocative, 1912. Ink on paper, 29 x 24.6 cm. Catalogue No.: 072335-D. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[64] helios gomez_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/64-helios-gomez_1.jpg)

Helios Gómez. Lerroux le traitre…, 1936. Engraving, woodcut on paper, 29.5 x 27.5 cm. Catalogue No.: 214105-011. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[65] casas_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/65-casas_1.jpg)

Are there other types of colour-based humour? Would you say that the activist Helios Gómez could be considered a representative of red comedy or that this tile by Ramon Casas has something to do with brown comedy?

Ramon Casas. The advances of the 20th century: the toilet, 1899-1903. Clay tile, 13.5 x 13.5 cm. Registry No.: 847. Museu d’Art de Sabadell.

A thousand ways to laugh

«No mind is thoroughly well-organized that is deficient in a sense of humour.» Samuel Taylor Coleridge

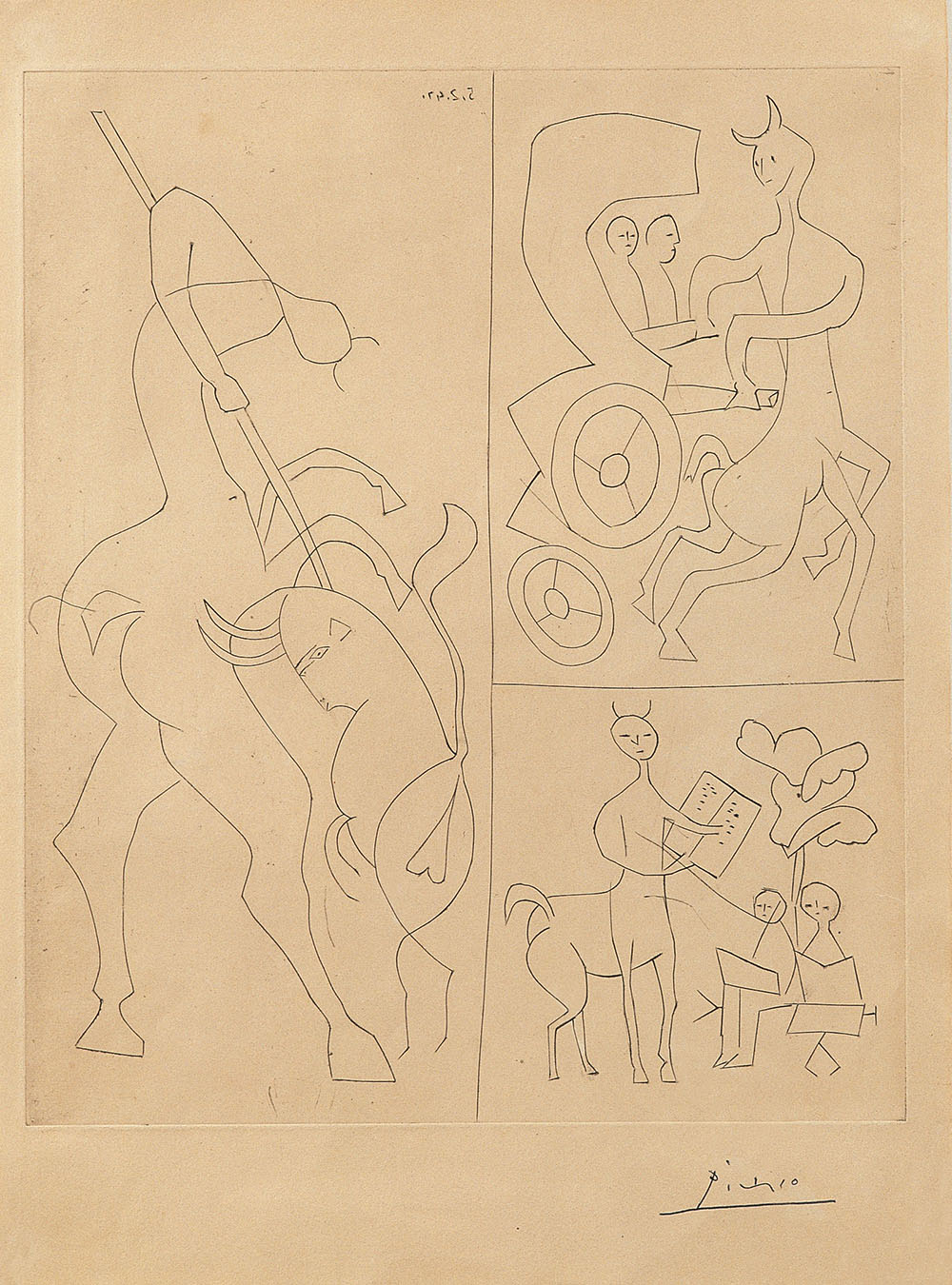

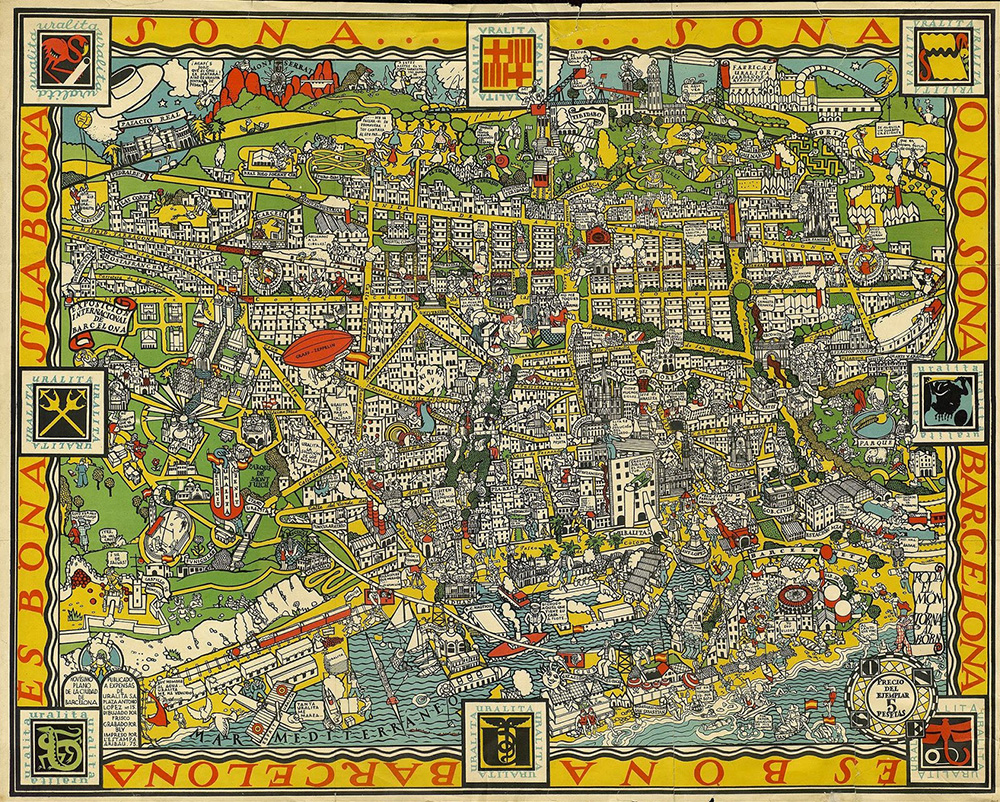

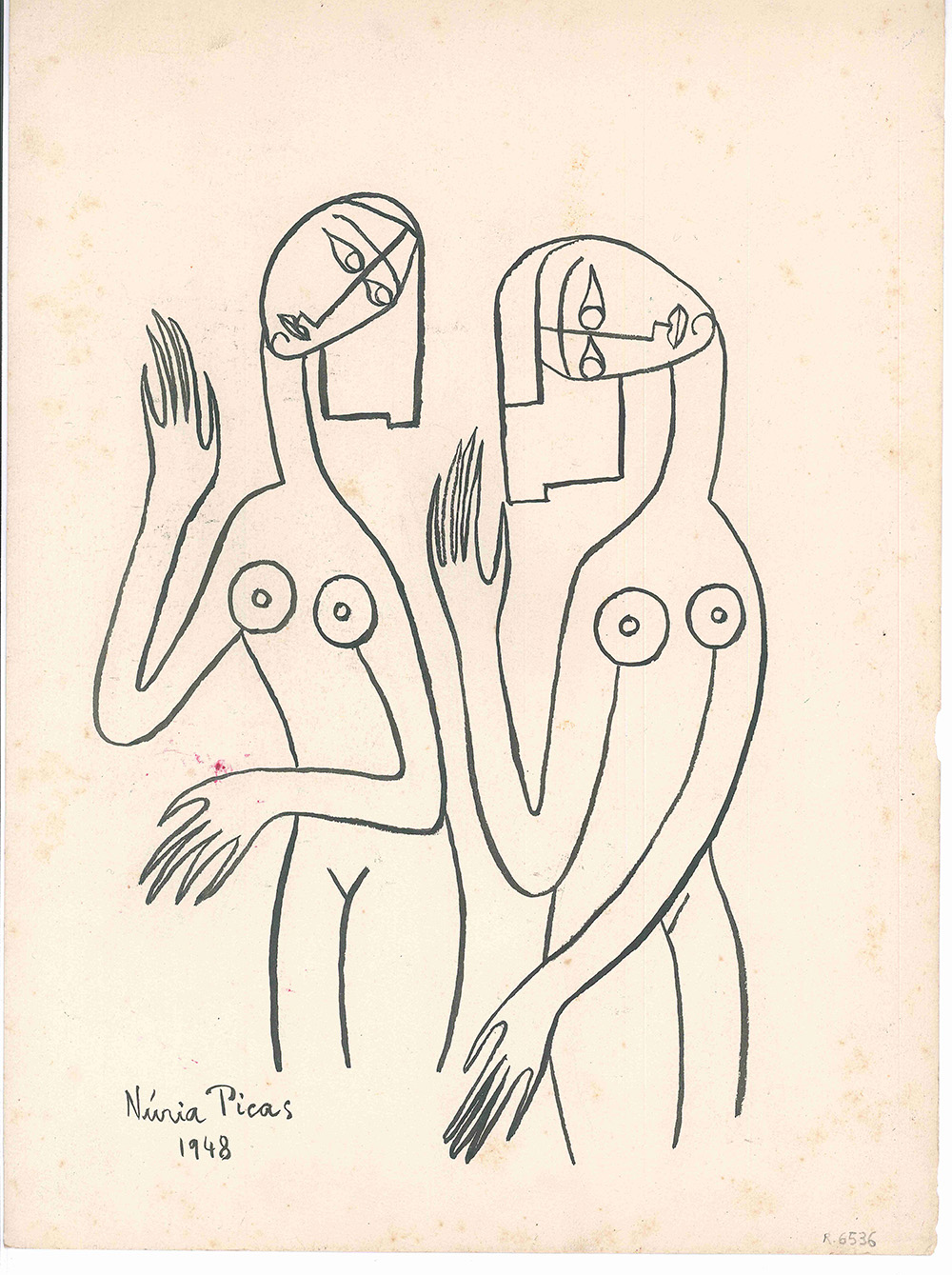

A thousand? No. There are not a thousand ways to laugh. There are more than one billion ways to laugh. Laughter breaks out among friends, and we love sharing it. But our sense of humour, that is, that which does or does not make us laugh and which modulates the intensity of our response faced with humorous stimuli, is an entirely personal thing, something that cannot be transferred. It is intimate, unique, and precious for every person that is (and has been) on the planet. We know for sure that part of these aspects have a social and cultural origin, and we learn and internalise them until they form part of who we are. There is a social strain of comedy, which takes shape in the popular revelries and festivals, channelled by the comedians, clowns, buffoons, and dummies in popular imagery, such as Cucut and Xurruca, and another type of comedy that is personal and private, which thrives in shared experience, like the one that connected Ramon Casas and Santiago Rusiñol. Humour plays with meanings and contexts, just like Picasso did in working with centaurs, along with small details, like the exquisite map of Barcelona that Frisco drew for the 1929 Expo.

Martí Casadevall i Mombardó. Cucut and Xurruca, 1906. Wood pulp, 100 x 93 x 89 cm. Registry No.: 2602. Museu de la Garrotxa.

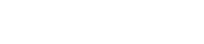

Ramon Casas i Carbó. Rusiñol on top of a wrought iron lamp. Barcelona, 1893. Oil on canvas, 199.8 x 99.7 cm. Museu del Cau Ferrat, Sitges. Santiago Rusiñol Collection, inv. no.: 32.008. 32.008. © Arxiu Fotogràfic del Consorci del Patrimoni de Sitges.

Pablo Picasso. Several Occupations of the Centaur: Picador, Carthorse, School Teacher. Paris, 5 February 1947. Burin on copper; printed on Arches laid paper (II state and definitive), 30.9 x 25.7 cm (plate); 37.9 x 28 cm (slide). Illustration for Ramon Reventós, Two tales. Paris-Barcelona, Albor, 1947. Palau Foundation, Caldes d’Estrac. Registry No.: 203. © VEGAP.

Frisco Millioud. Poster for Uralita / Barcelona Universal Exposition, 1929. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Núria Picas. Female Figures, 1948. 32.5 x 24 cm. Registry No.: 6536. Museu Abelló.

Laughing at the dead and those holding vigil

«Humour is the highest expression of the adaptive mechanisms.» Sigmund Freud

Built on misunderstanding, nurtured by impertinence, the secret to humour is that it reveals the contradictions that we typically take for granted in exchange for living in society. Most social institutions, the relationships established in a community and the behaviour demanded of us in order to be part of the group, when viewed with a cold objective gaze from a distance, become ridiculous. That is why comedy can be offensive, because it calls into question some apparently fundamental points. Jokes and transgression are socially accepted, but only up to a certain point. Beyond this limit, intransigence appears. It is nothing new to say that throughout the centuries and even today the main topics banned in comedy have to do with political and religious power. Comedians become professionals in transgression, diligent dispensers of criticism.

![[71] magnat_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/71-magnat_2.png)

Anton Sohn. The Magnate (Dance of death), first quarter of the 19th century. Polychrome terracotta. Registry No.: MFM S-25560. Museu Frederic Marès.

Das Pastoras. El Víbora, Special Christmas Issue, 1988. Barcelona [La Cúpula], no. 107. 107. 26.5 x 20.5 cm. Registry No.: A12015.103. Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona. MACBA Collection, Research and Documentation Centre.

Miguel Gallardo. The history of the church, 1979. Chinese ink and mechanical patterns on paper, 50.3 x 35 cm. MORERA Collection. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida. Donation by Miguel Gallardo, 2019.

Laughter in postmodernity

«Count your age by friends, not years. County your life by smiles, not tears. » John Lennon

Humour is alive and its heartbeat changes along with society. What makes us laugh today may not have the same effect next week. Or vice versa: today’s tragedy may become comedic material over time. Ramon Casas parodied the ancient craft tiles with his Advances of the 20th century, recreating the aesthetics while updating the contents.

![[74] adelantos_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/74-adelantos_1.jpg)

Ramon Casas. The advances of the 20th century, 1899-1903. Preparatory watercolours for a series of tiles, 13.5 x 13.5 cm. Registry No.: 806, 807, 808, 809, 810, 811, 812, 813, 814, 815, 816, 817, 818, 823, 824, 827, 828, 829. Museu d’Art de Sabadell.

![[75] rodolí_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/75-rodoli_1.jpg)

Salvador Dalí and Carles Fages de Climent. The triumph and the couplet of Gala and Dalí, 1961. Auca cartoon, 63 x 43.5 cm. ME 2424. Museu de l’Empordà.

![[76]cram_2](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/76cram_2.jpg)

Marc Aleu, under the pseudonym of Cram, imported modern humour onto the pages of an issue of Dau al set that broke free from the framework of slapstick humour found in the comedy magazines during Franco’s regime. Mariscal designed a set of salt shakers, ironically playing with shapes and pop references.

Cram (Marc Aleu). Dau al set. Without words, 1954. Publication. Ink printed on paper, 25 x 18 cm. Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

![[78] alfons lopez_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/78-alfons-lopez_1.jpg)

Meanwhile, Alfons López includes topical references from multimedia and television culture into his vignettes.

Alfons López and Xavier Roca. Channels (Aníbal i Victòria Series), 1996. Chinese ink and watercolour on paper, 39.6 x 32.7 cm. MORERA Collection. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida. Donation by Alfons López, 2016.

![[77]mariscal_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/77mariscal_1.jpg)

Every manifestation of comedy is built on references that must be shared by the joke teller and the audience. If the joke gets bundled up too tightly in the context, the humour dissipates and fades away.

Javier Mariscal. J. Klandinski (salts, condiment vessels), 1991. Porcelain, 9.9 x 6.5 x 5.2 cm. Registry No.: MADB 136364. Museu del Disseny.

Epilogue: whoever doesn’t know how to laugh doesn’t know how to live

Laughter bursts forth from your lips for a brief moment, then it fades away, yet the memory can keep you warm for a while. A smile can be drawn on your face at any time, making everything light up. As Joana Raspall wrote, “just by giving me a smile, as you walk by, I’m filled with joy, and I see a wider world”. A laugh is a gem, a small treasure that grows when shared, and it reminds us of the profound beat of life deep in our hearts. Laughter enriches us because it makes us feel more alive. And being alive is undeniably better than not being alive. Laugh. Laugh, because life is short, and sadness steals it from us.

![[80] eva_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/80-eva_1.jpg)

Eva M. Ramon. Me, you, her…, 2013. Digital print. Registry No.: ME2885. Museu de l’Empordà. Donation by GEES (Grup d’Empordaneses i Empordanesos per la Solidaritat), 2021.

![[79] coll_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/79-coll_1-scaled.jpg)

Josep Coll. Capturing a bomb, 1950. Ink and pencil on paper. Catalogue No.: 254290-000. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

![[81] nogues_1](https://xarxa.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/81-nogues_1.jpg)

Xavier Nogués (Babel). Uix!, 1922. 1922. Ink on paper, 15.7 x 19 cm. Registry No.: 657. Museu d’Art de Sabadell.