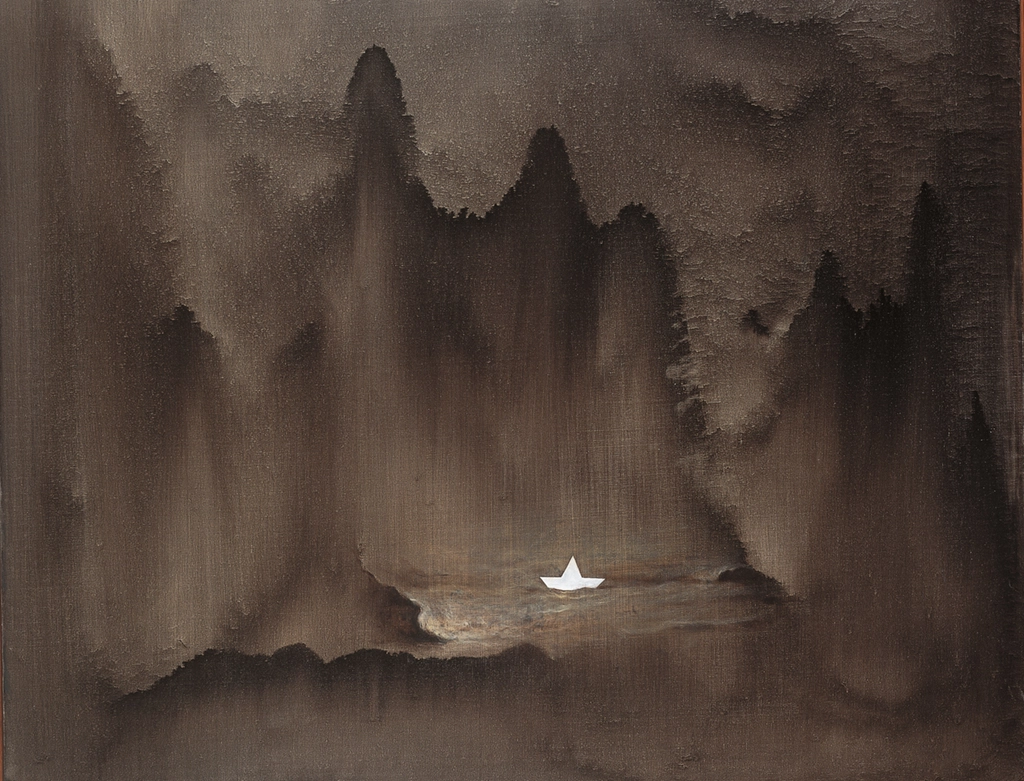

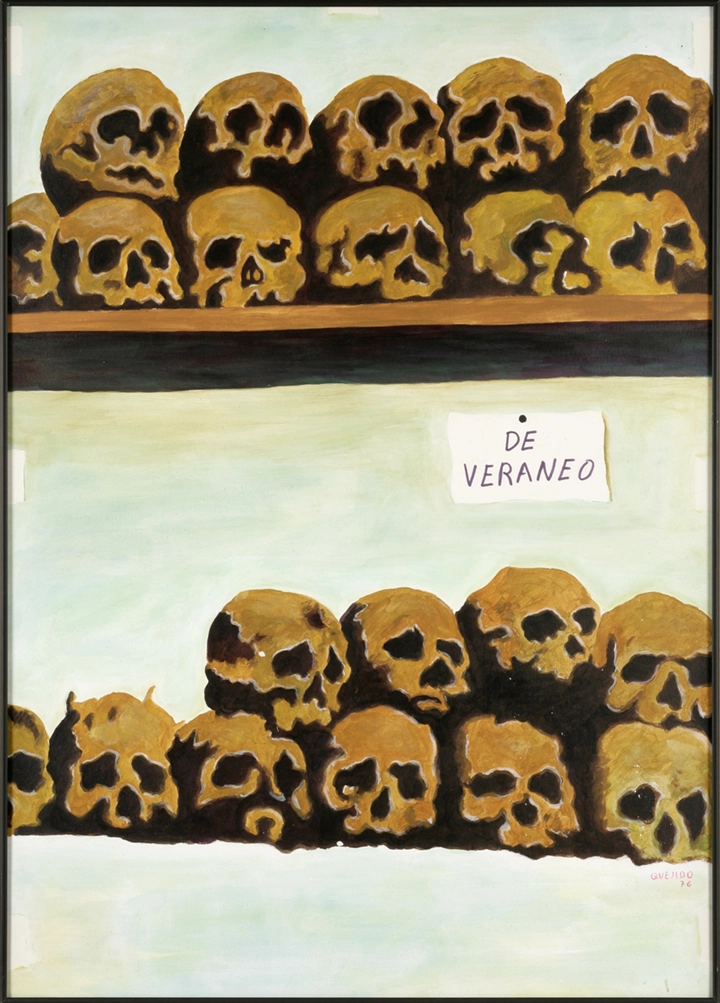

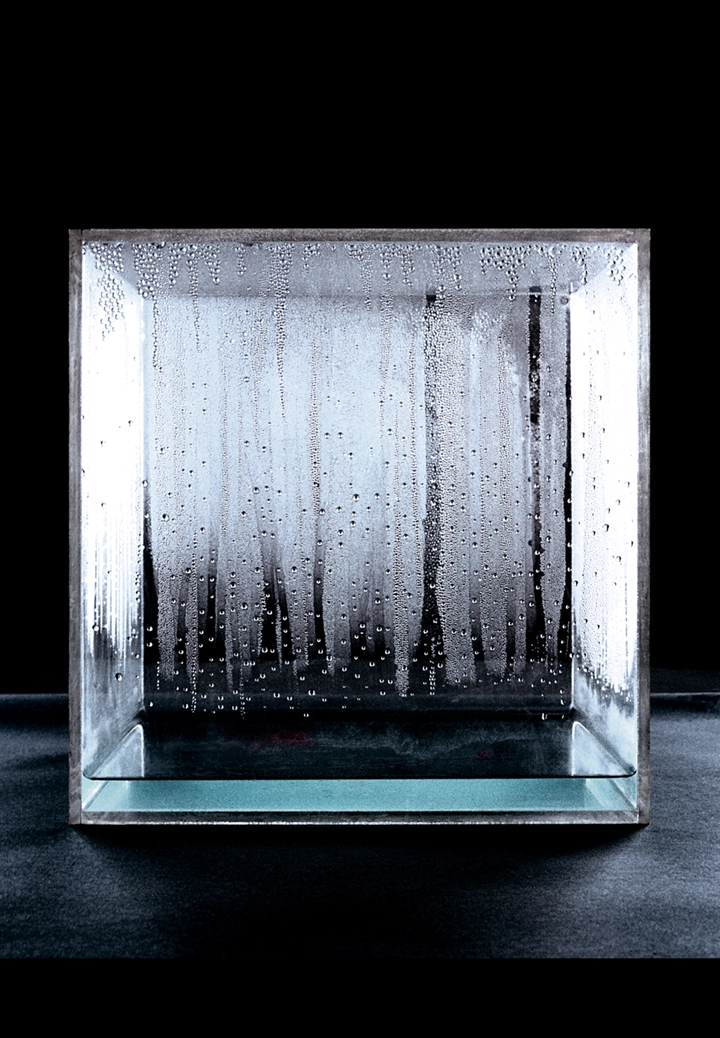

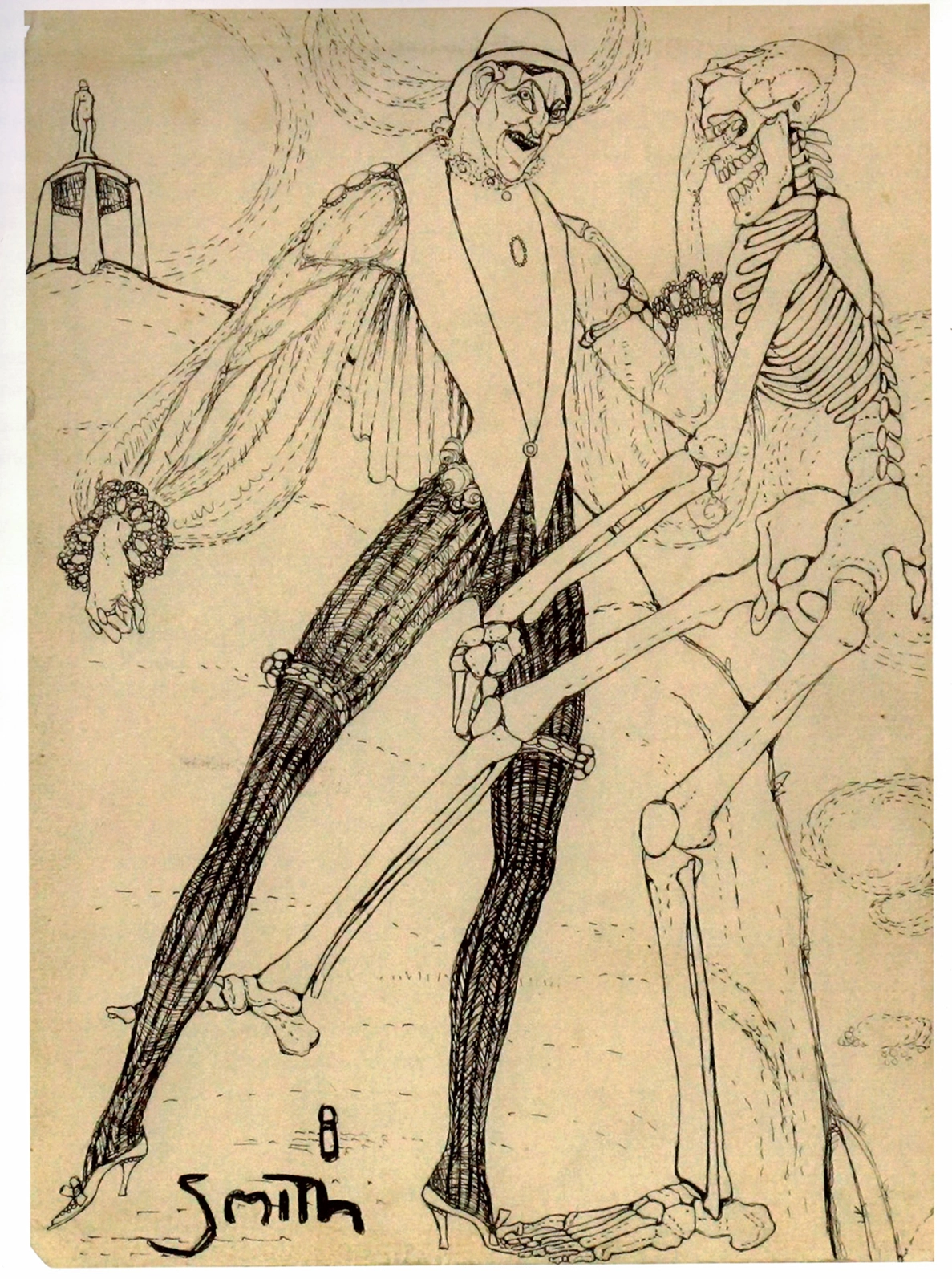

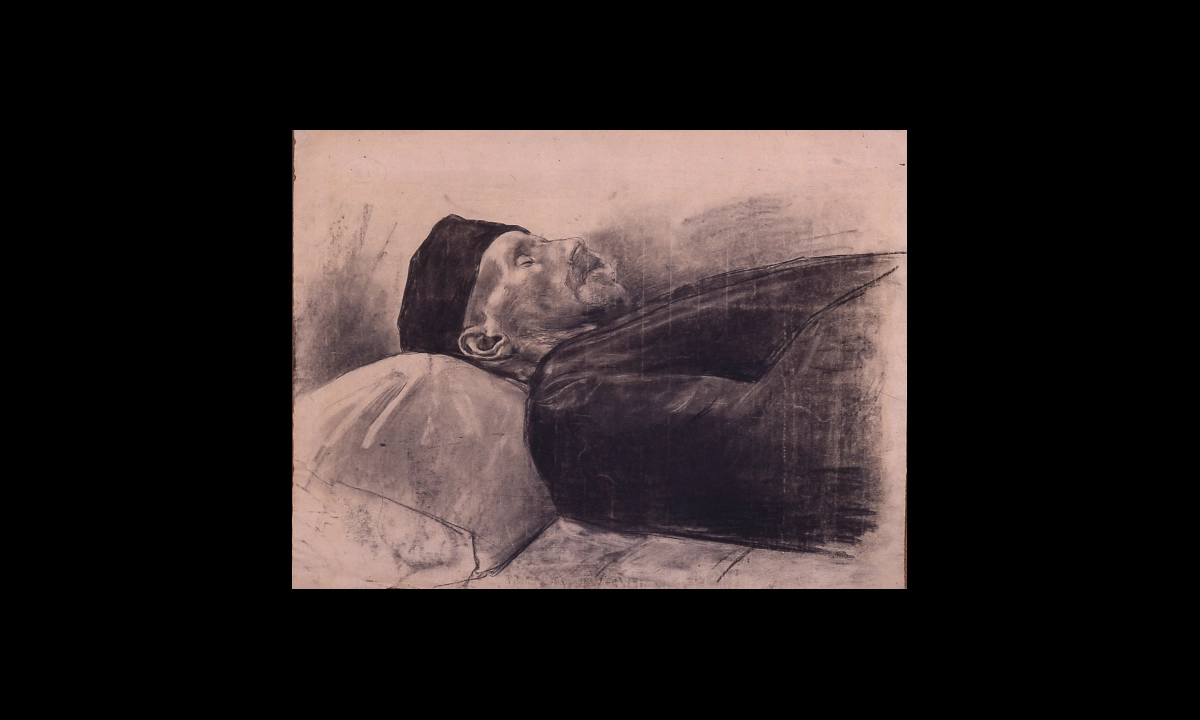

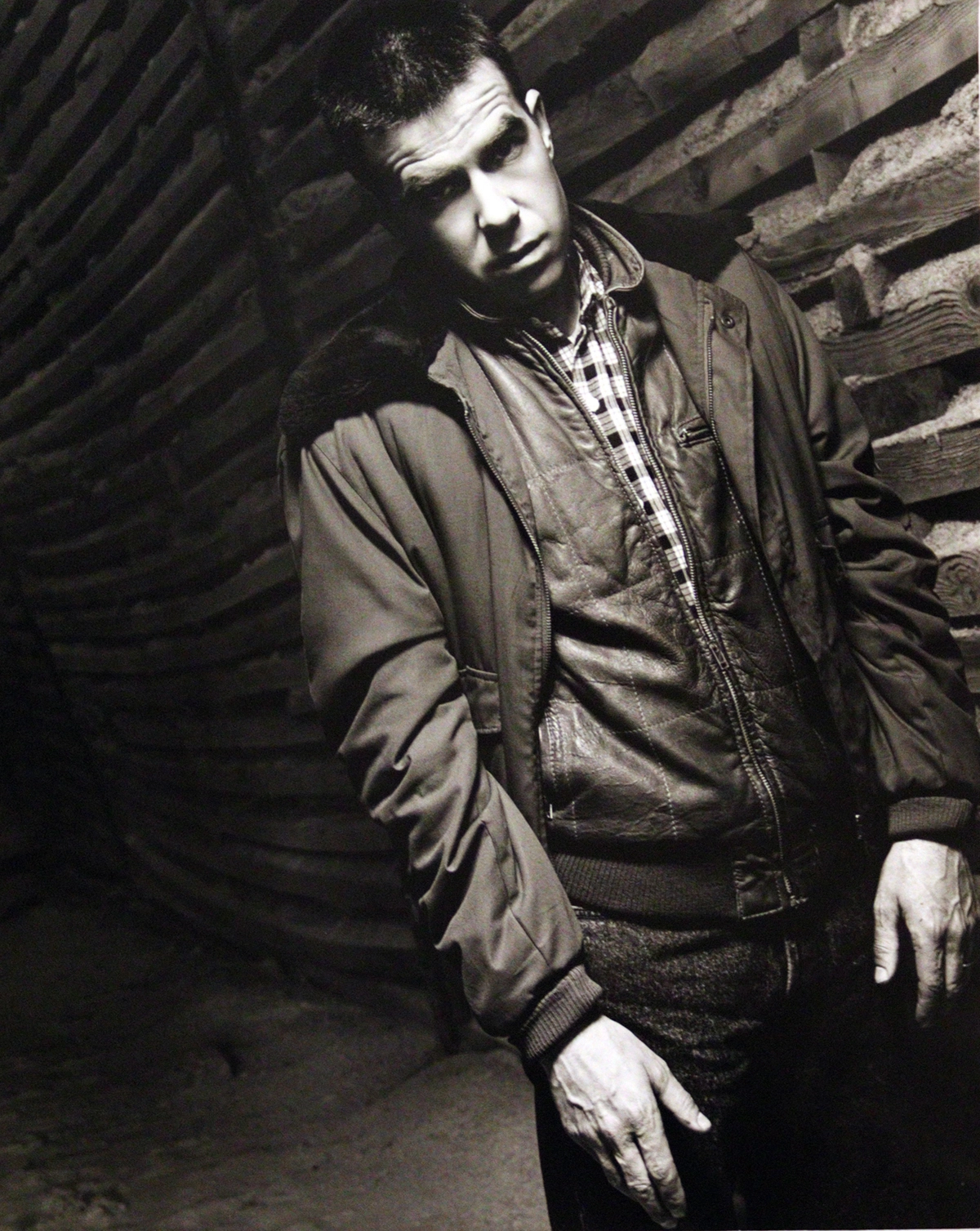

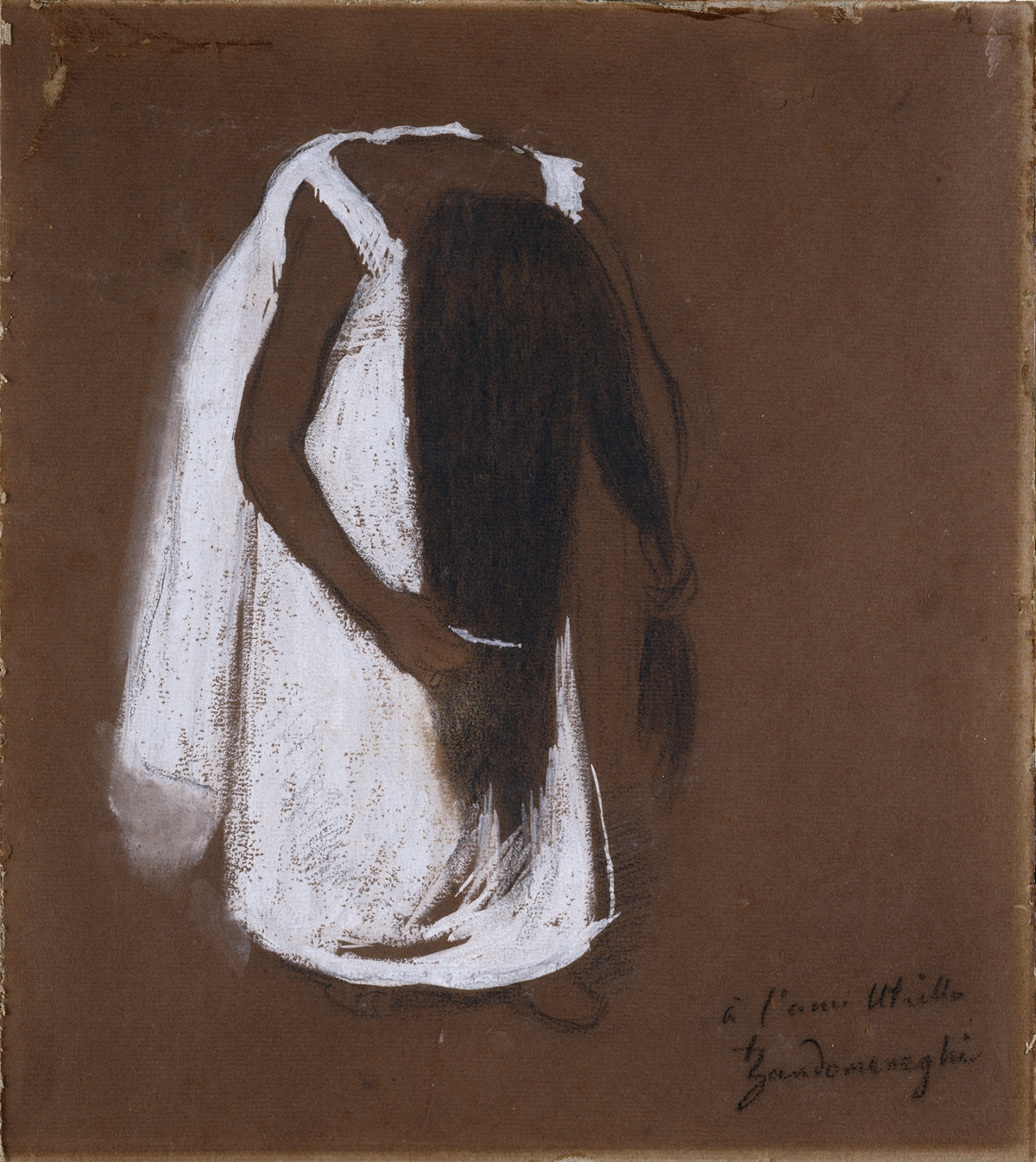

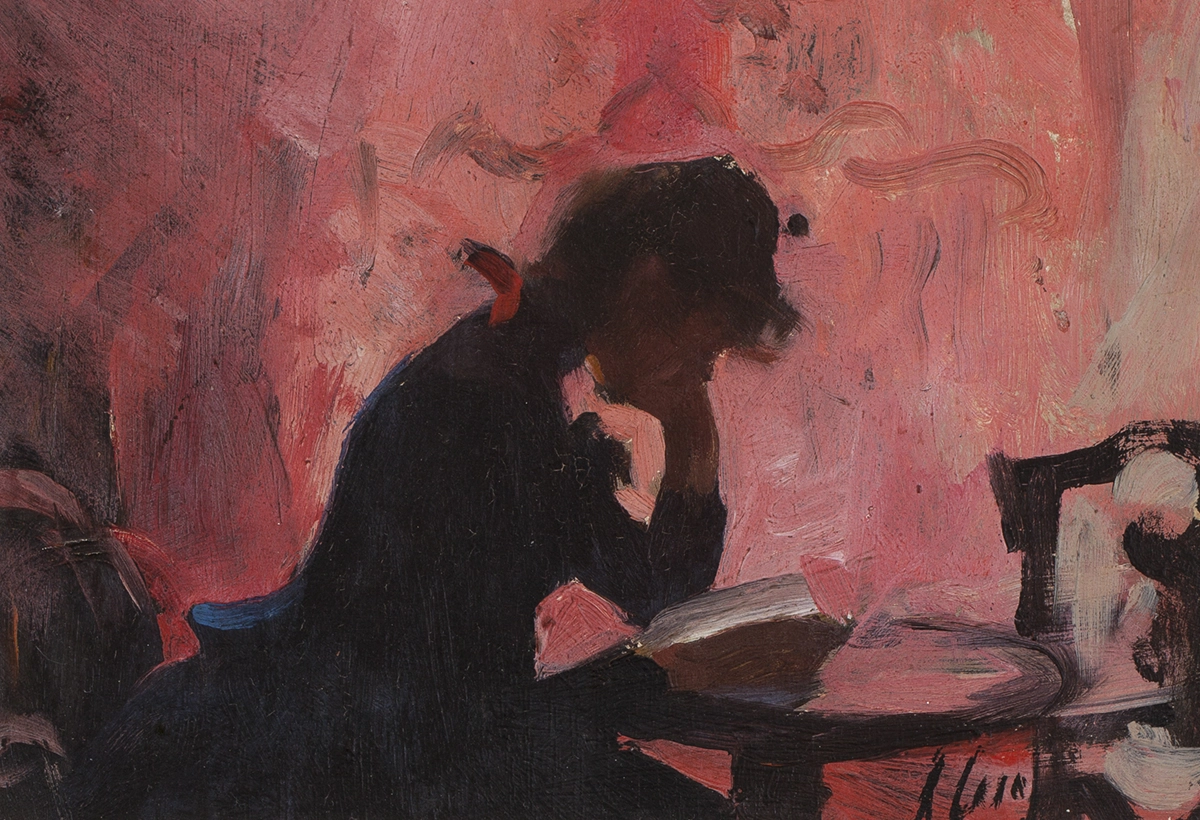

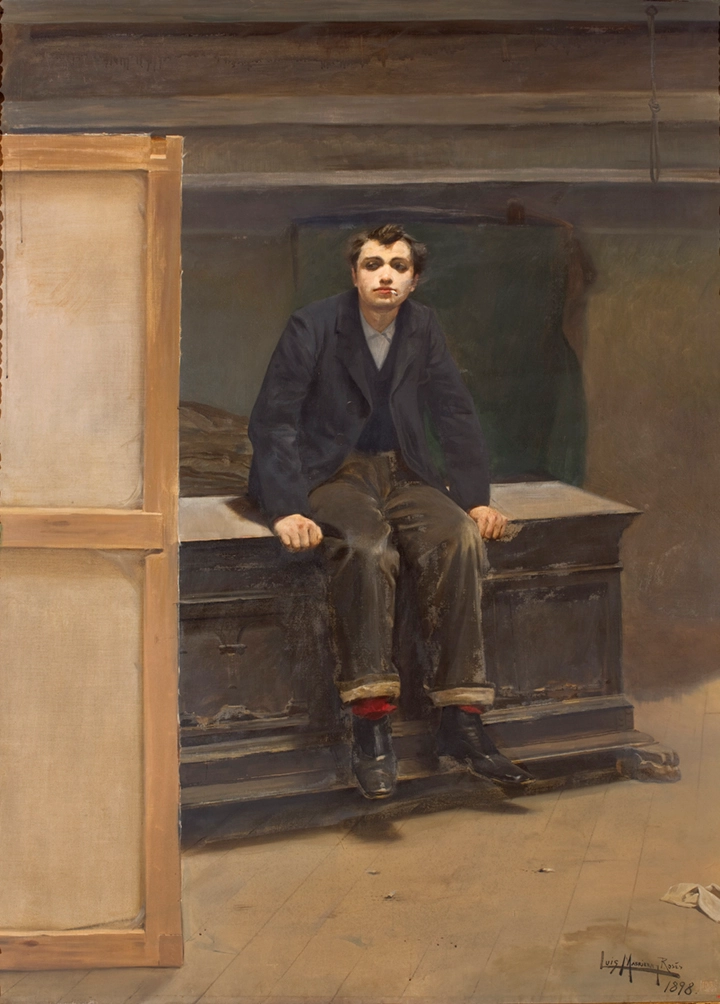

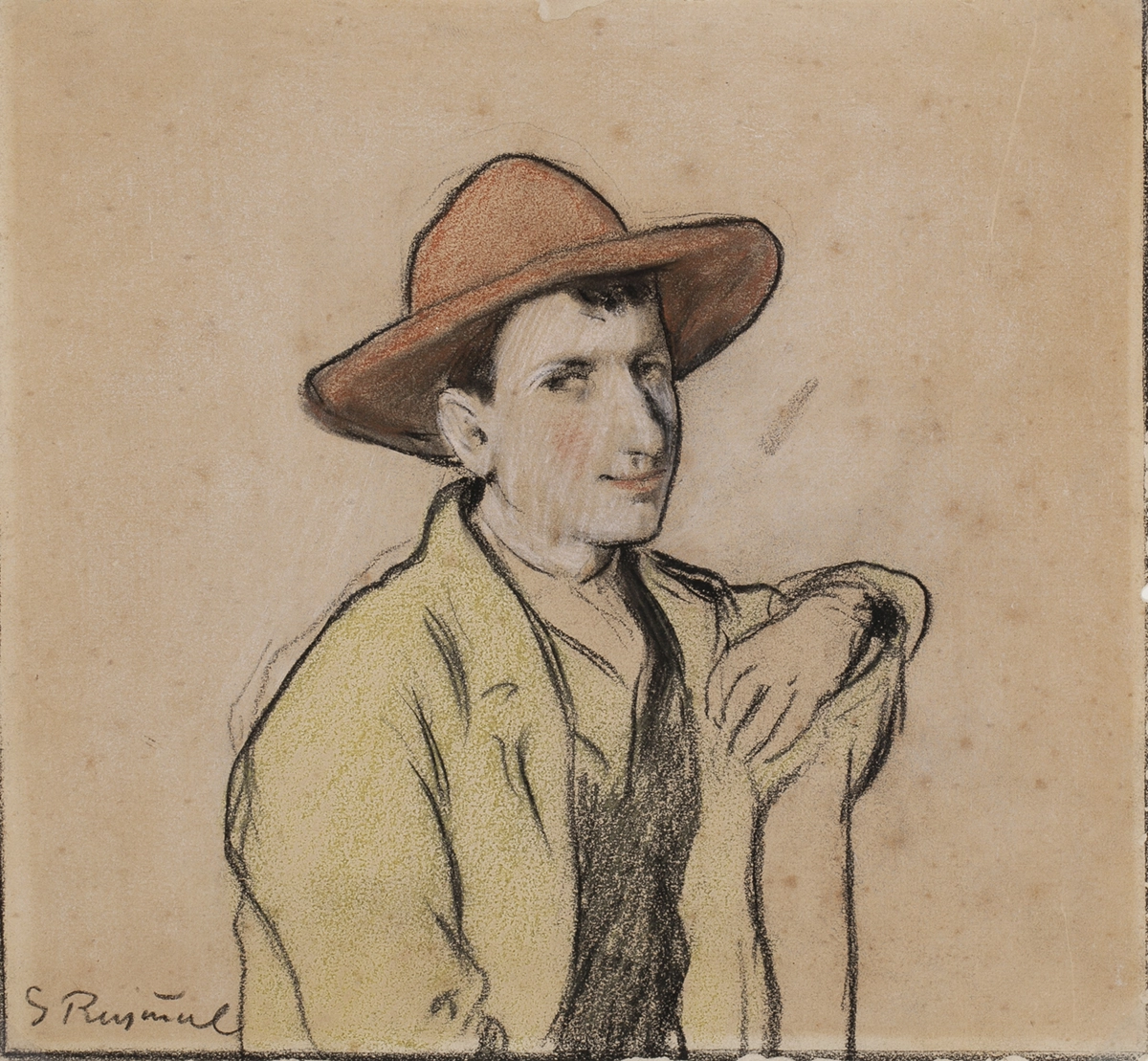

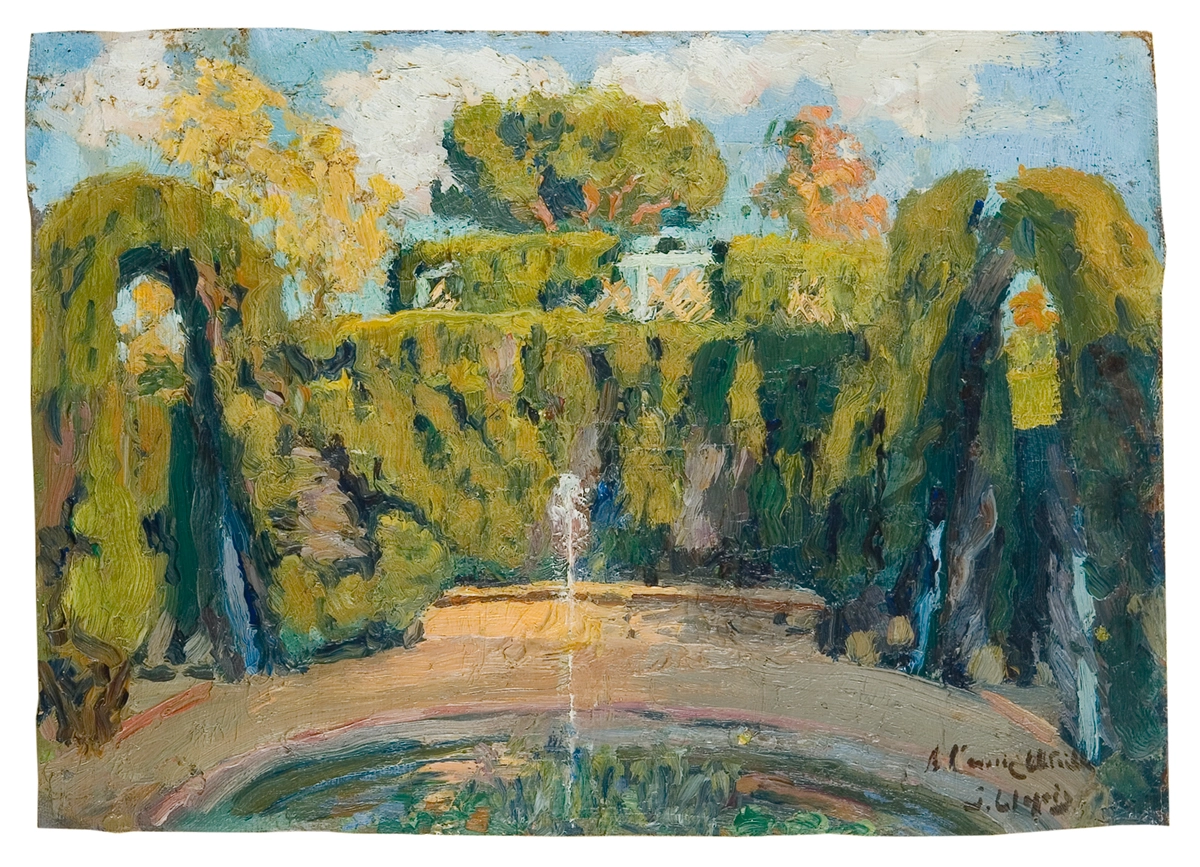

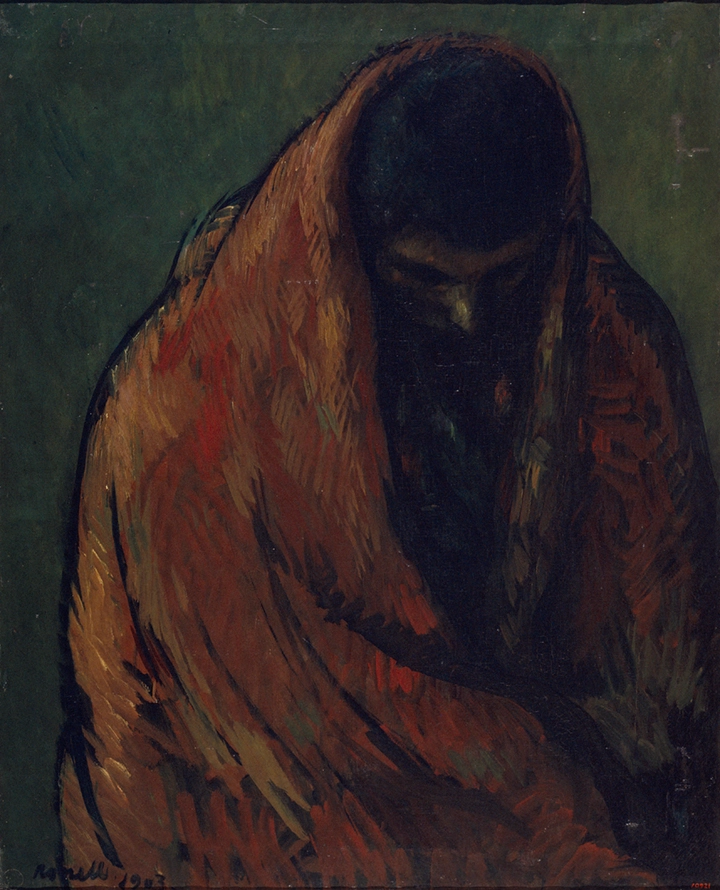

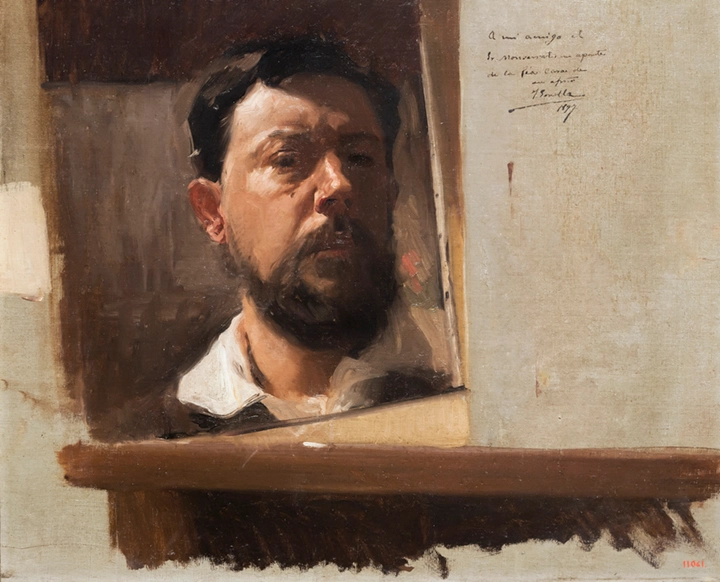

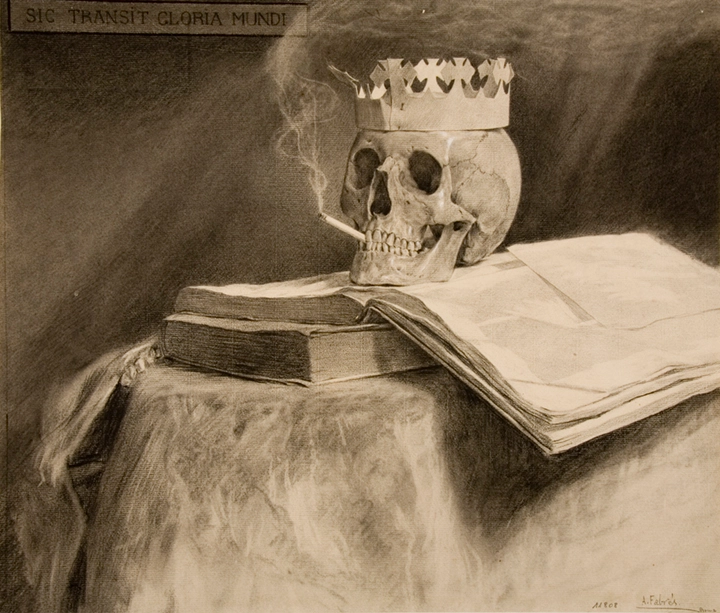

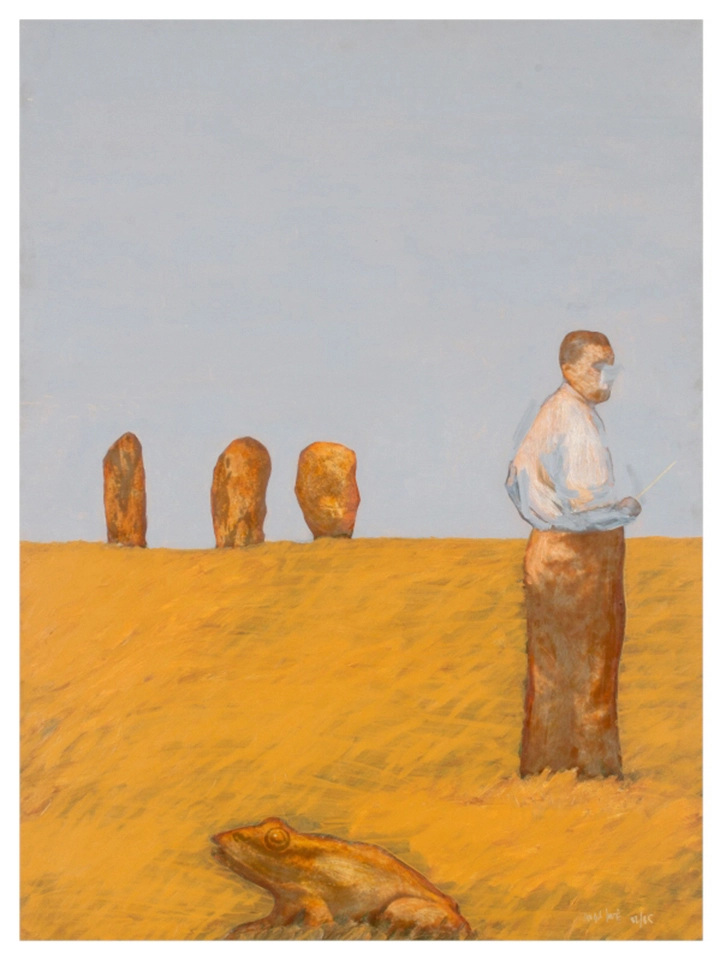

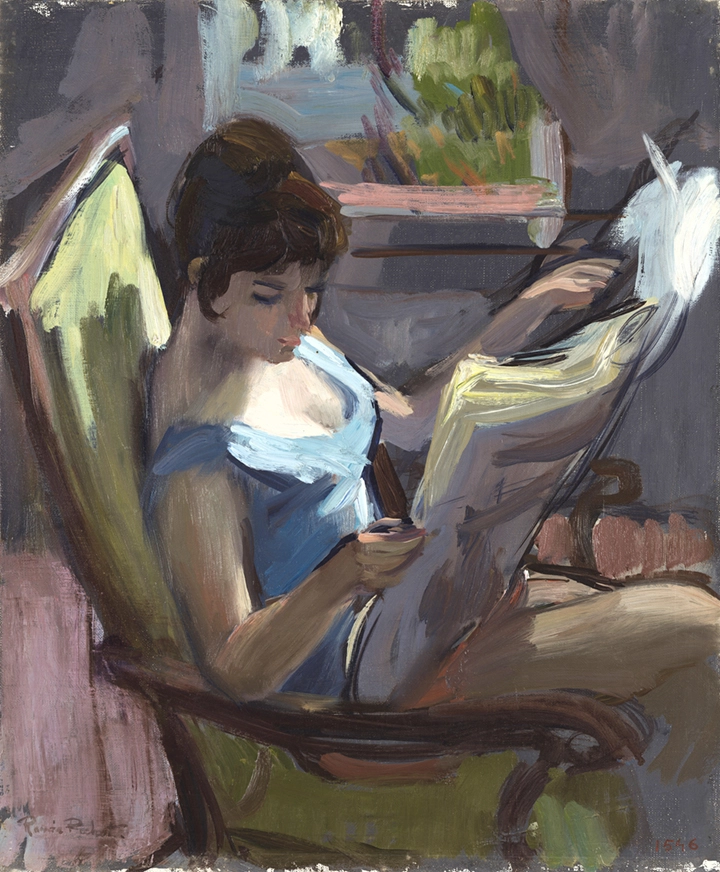

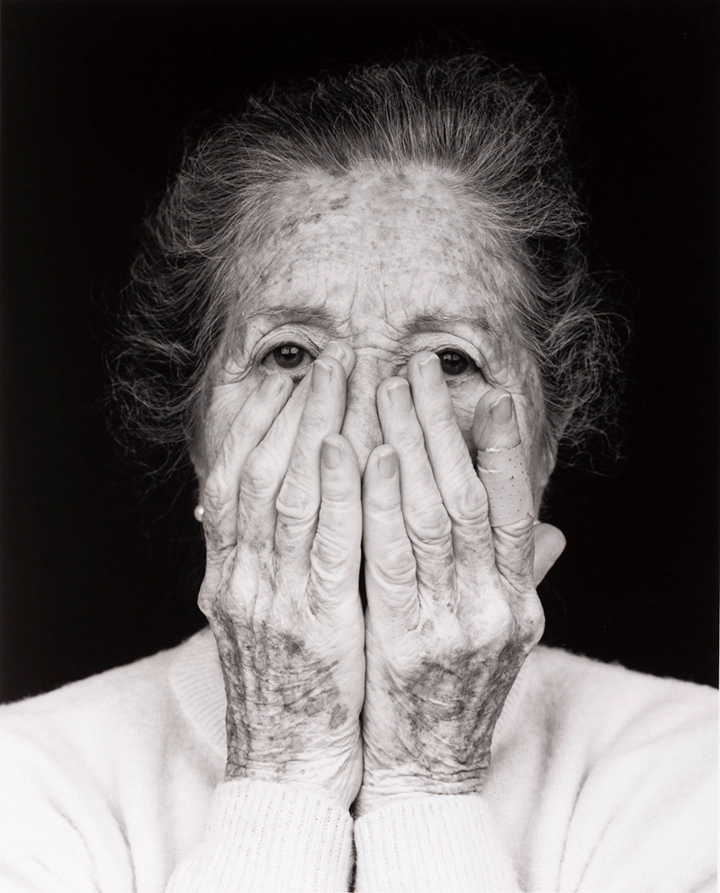

A search for works from the past to mirror us in the present.

Curator: Jordi Mitjà

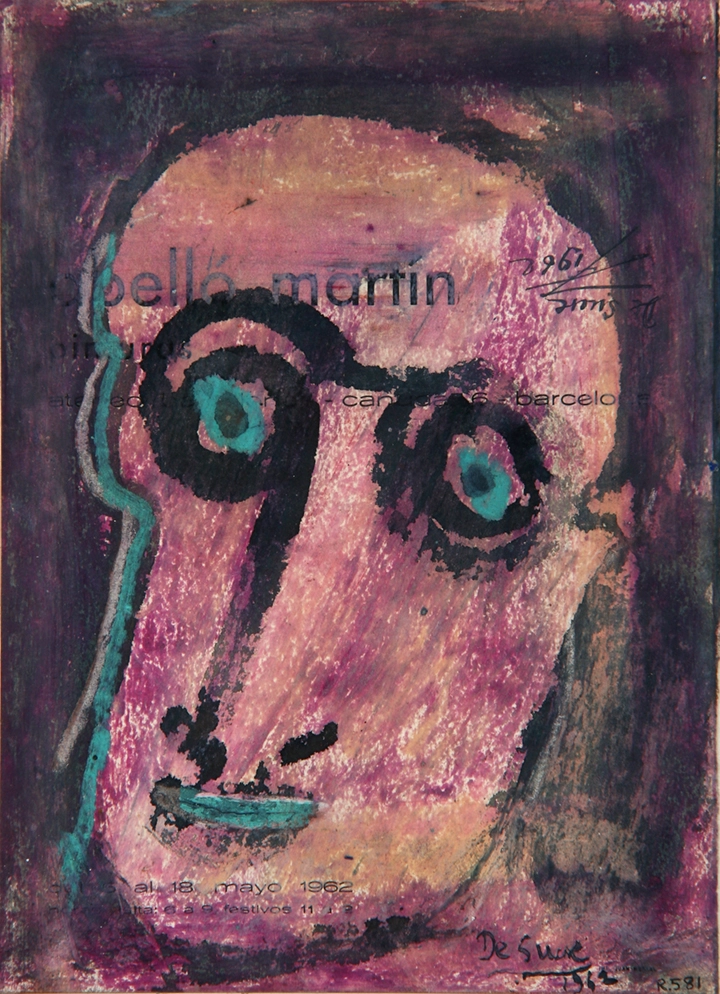

Locked down eyes

Mirroring ourselves and projecting the reflections.

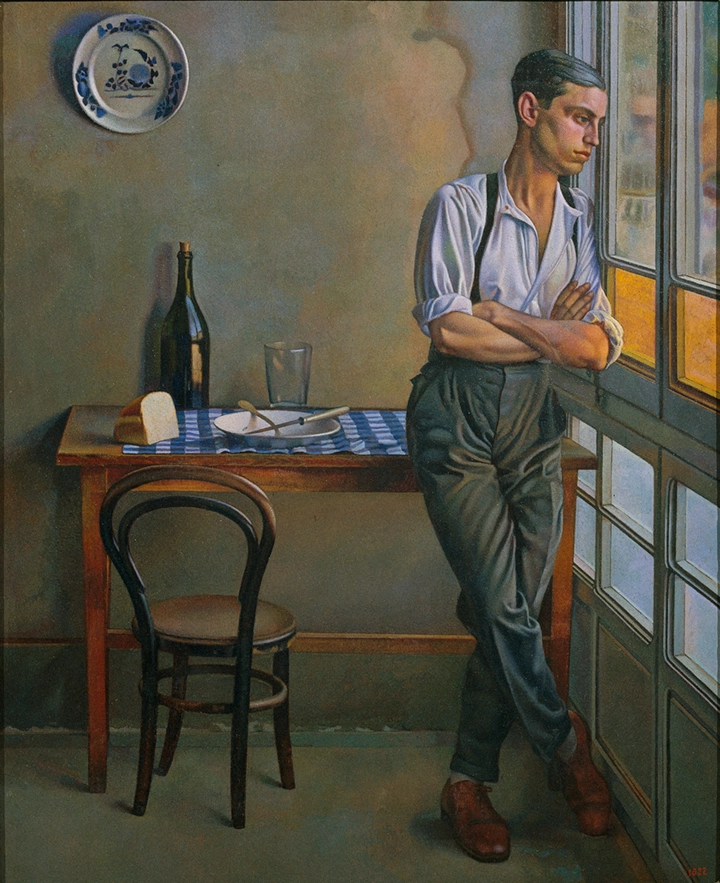

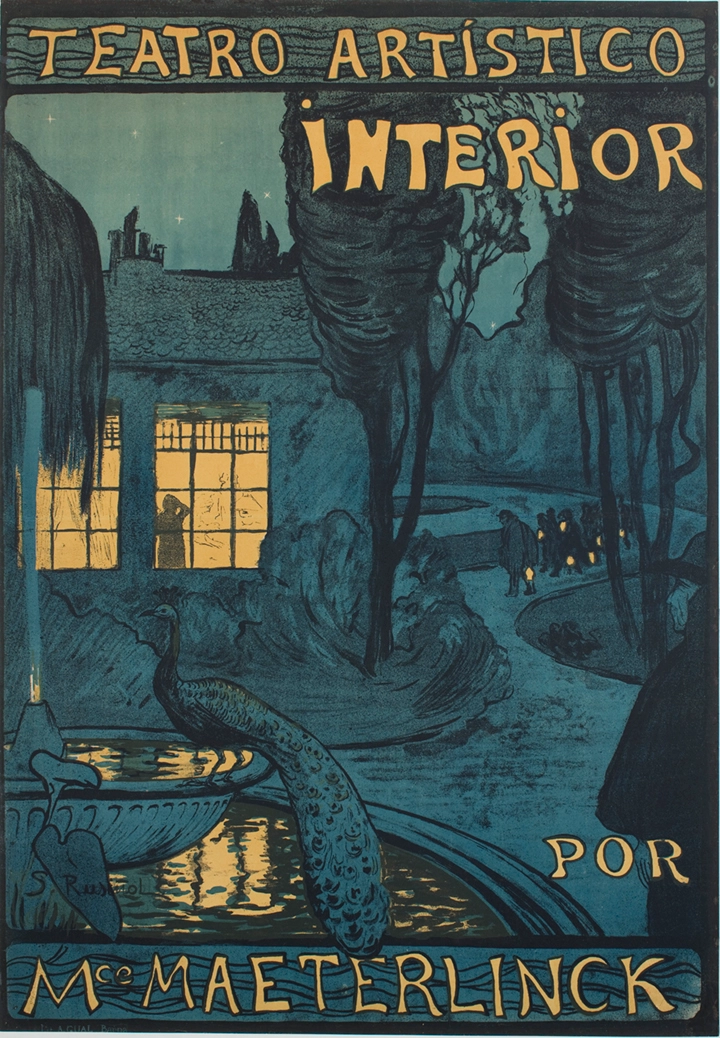

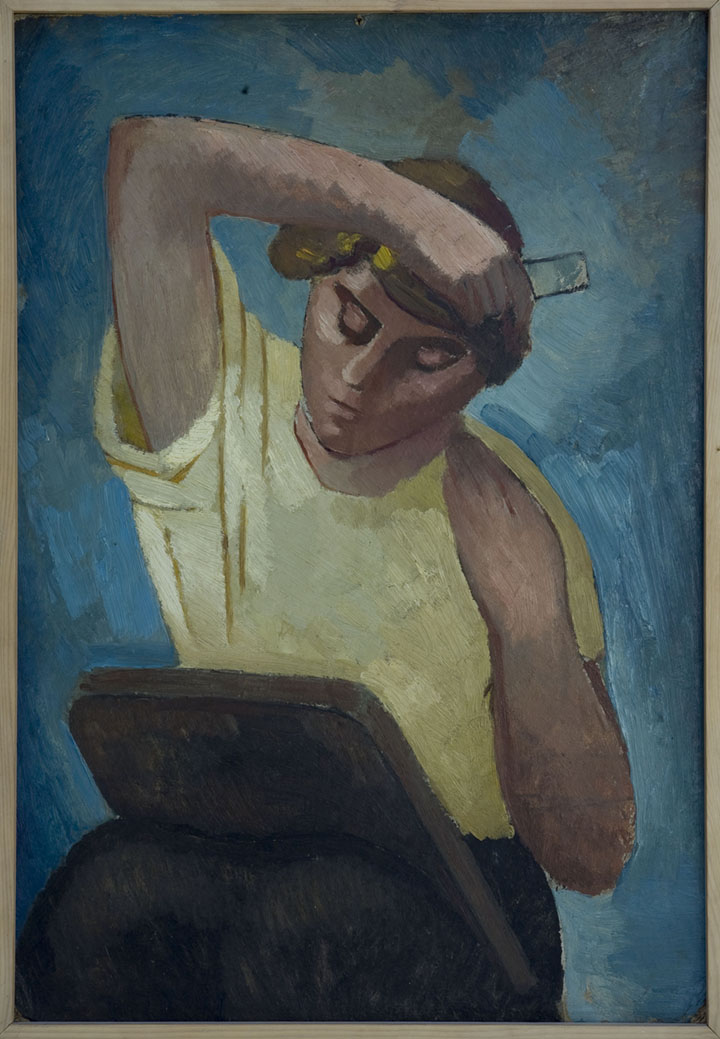

Locked down eyes is a juggling act or a play of mirrors, depending on how you look at it. No one should be offended by the audacity of searching the Network of Museums of Catalonia for works of art that, under very specific criteria, correspond more or less subjectively to what we have lived through as a society during this first stage of the Covid-19 pandemic. Situations that, translated into images, into reality or the many diverse realities, we have not looked at exhaustively.

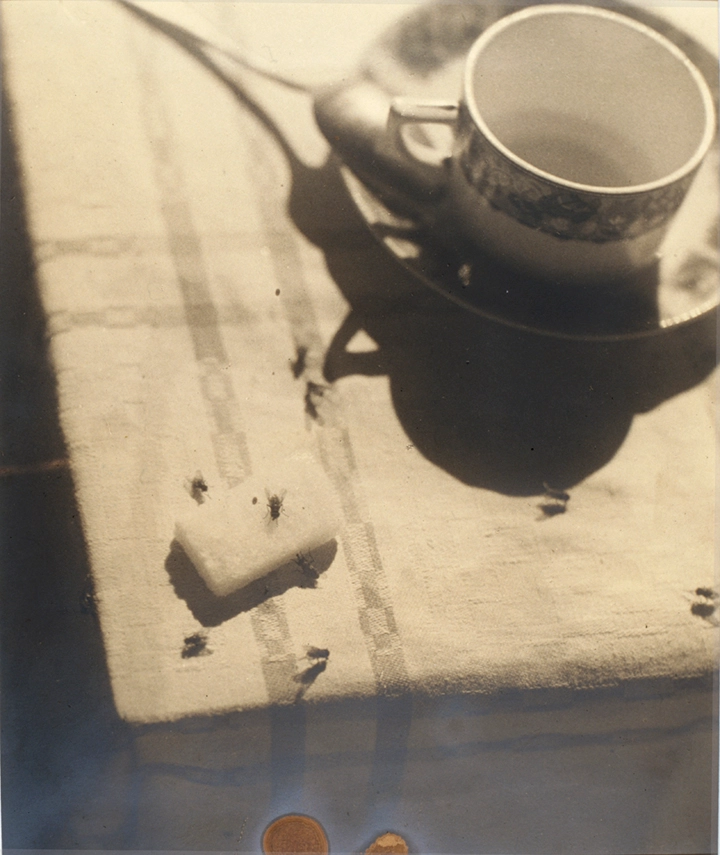

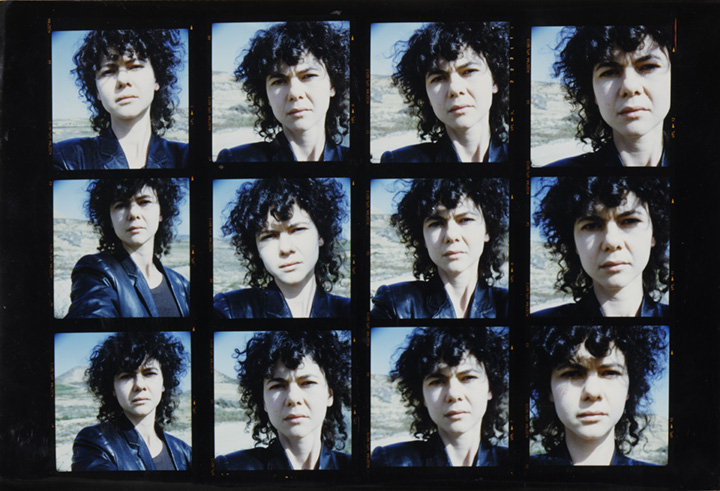

Now we can state openly that we do not have all the possible takes, beyond the home-made images that have circulated on social media. Photographs and videos of experiences that, as they are unknown, we are still assimilating. All the experience of the fear; of being shut in our homes for such a long time; of having to work under the stress of becoming infected; of a frightened health system on the point of collapse; of hidden but implacable death with its rituals silenced; and, above all, of the dire experiences in care homes, the major black hole in the system. All these have been so brutal that we are still assimilating their effects.

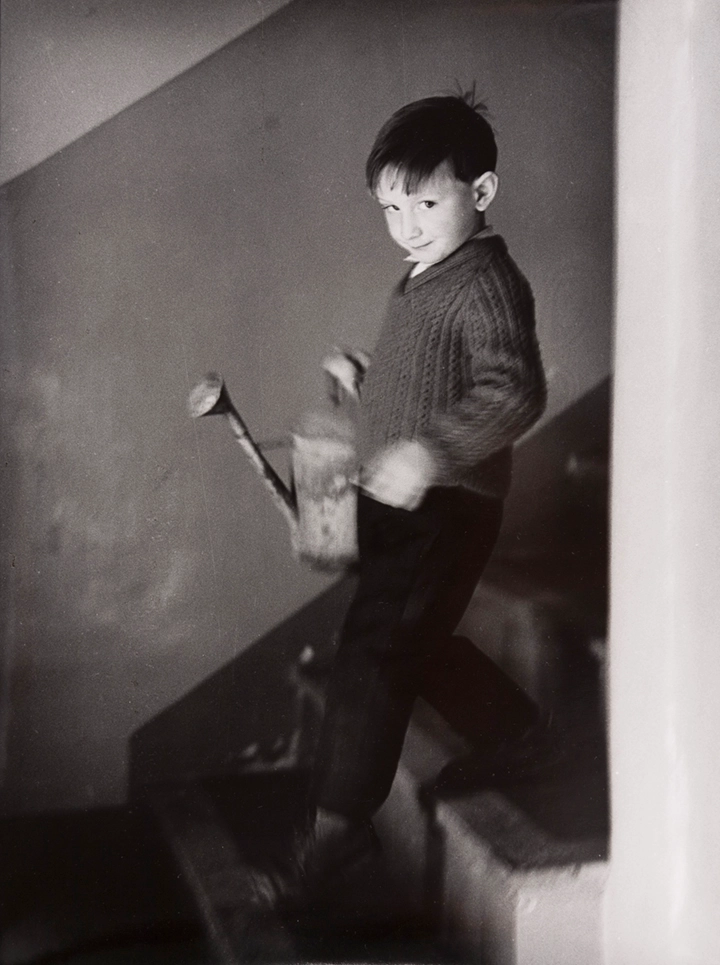

At the same time, the collective experience of events makes complete sense in the personal and inseparable environment. What we have lived through and what we have perceived as a group can be drastically separated. I propose we focus on the people and avoid the erratic, always impersonal data from events that we will remember for the rest of our lives. The project you have before you, this heterogeneous collection of images, artists, techniques, etc. from different periods, corresponds to a series of questions I asked myself, intuitively, during the first month of lockdown. Questions greatly influenced by a surprising and sadly disquieting situation. Fear intensifies the inability to think about the present and this project emerges from that feeling

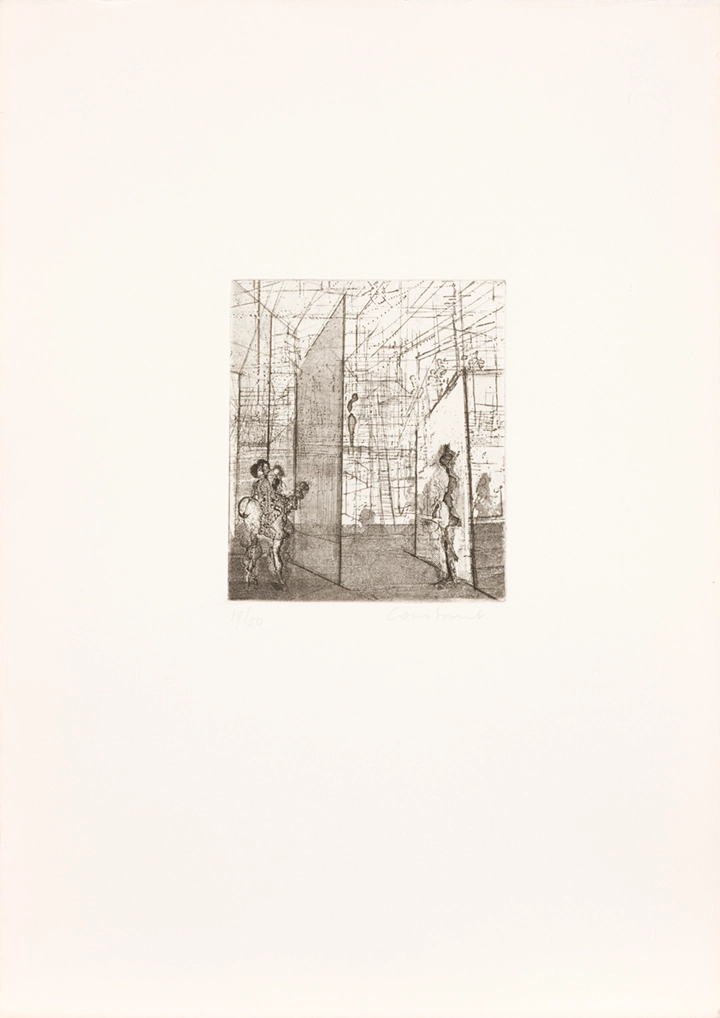

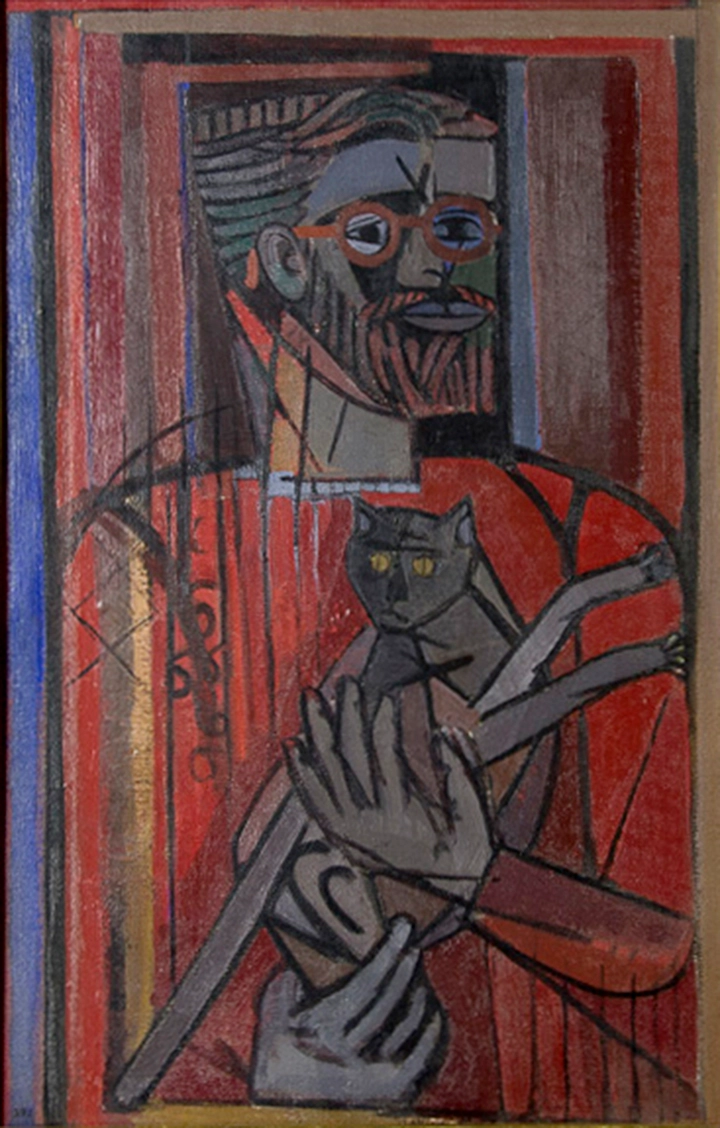

Recently, some museums in Catalonia and other parts of the world have suggested people stage or personify works of art posed in domestic scenes that they then photograph and display next to the original painting or sculpture. The institutions encouraged them to upload the scenes and tag them on social media; it was like a game to play at home with no pretensions, but it certainly magnified some of the icons of art. Above all, however, it made sense as part of the museums’ task of cultural propagation. While I thought about the many possibilities offered by the virtual exhibition I had been commissioned to organise, I saw how families, young people, etc. reproduced, like a play of mirrors, highly recognisable works of art and others that were not so well known. They staged them as home-made museum exhibits, while, at the same time, reminding us that we were unable to visit the actual museums, which were closed at the time. They were reproductions of reproductions by performative and highly original copyists.

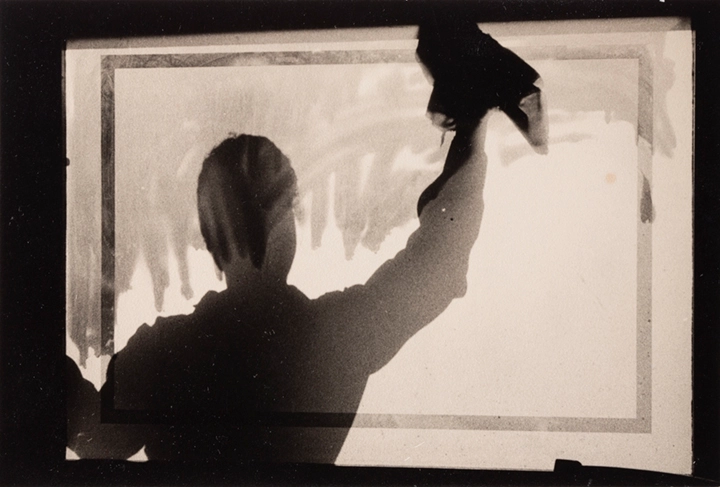

That phenomenon chimed with me and I began to weigh up some of the challenges linked to the intensity of the work of the past and whether those contrivances we refer to as works of art have the potential to help us understand or explain the extraordinary events of the present. Locked down as we were, that viral practice of staging scenes, which was by no means new, reached new levels of ingenuity and I decided definitively on a proposal that would speak to us of an unusual situation, mirroring ourselves in the works of the past. Interpreting the present, choosing those original works past and betraying their original meanings. What I have imposed bears no apparent relation to those stagings I am speaking of, but they do have to do with the hidden power of the also-locked-down works, in the sacrilege of making them speak of a matter that does not concern them, of reliving them momentarily. Locked down eyes is that; the attempt to stage an emergency situation with the archives deposited in the museums, with a content that aims to explain what is happening or what has happened to us, in the hope that the works materialised in this period will improve this whole intervention

Locked down eyes eyes is therefore a project in suspension, awaiting current works that will no doubt impact more incisively on the prismatic experience we have lived through, showing all its faces, the dark ones and obviously the most visible and most consented to by all.

All the project’s questions can be summarised in a single one. Can we find, in the diversity of the museums, works that in some way allow us briefly to use their discourses or their validity to comprehend and assimilate the exceptional state of a lockdown? In other words, can we reactivate a series of works from very varied historical periods to help us understand a situation that does not recognise them historically?

These and other uncertainties hover over a highly organic approach when it comes to choosing them. A selection made out of respect for the people who suffered and in a spirit of understanding and delving deeper into the unknown of a present that no longer does. Immediately after the lockdown ended certain images that had become iconic at the time were established as a kind of advertising. They were of people inside their homes or on balconies and terraces, and, above all of the staff in health centres. They were designed to cure us, to generate a political or cultural content of gratitude or of survival to the utmost degree. Locked down eyes has been prepared with many reservations, due to the lack of a prudential and temporal distance from all those stories and those that are yet to come out. Aside from the advertising, which has always had the ability to phagocytise and adapt to any situation, no matter how incredible it may be, the works of art produced during this forced confinement, and obviously those that will be produced after it, will have considerable resonance in terms of the present and future social significance of such narratives of insecurity, fragility and changing reality translated into iconography.

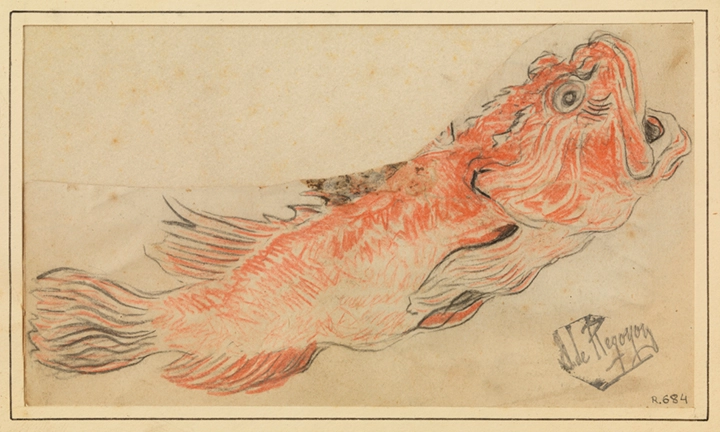

All the content generated from culture in a not-too-distant future will form part of museums and will, logically, be a reflection of the times we have been chosen to live through and will render this attempt at curating by yours truly obsolete. For that same reason and, in a way, to maintain the mystery that unfortunately runs through the exceptional events we have lived through, I decided to break with the thematic divisions that I myself formed to begin with. Instead I have preferred to show all the works mixed up, without indexing them, like a large box of experiences with no particular order, the closest thing to the actual situation or situations, as I said before. The difficulty in expressing an event from a prismatic ‒ almost unbelievable ‒ logic, the somersault of museum exhibits that illustrate a fleeting present.

This period of “hypothetical” post-lockdown has rewarded us with situations that have been more or less difficult, such as that I have attempted to grasp with this collection. At some point in the working process, initially with the indications addressed at the institutions and later with more meticulous research on museum websites, I attempted to adapt to new situations, confirming the genuine impossibility of capturing reality. The final choice into which you can plunge yourselves was generated over different intervals and finalised in late July.

Perverting museum conventions was one of the challenges, breaking in absolute terms with the conventions of historiography or historical temporality that, in another way, from the museum and the conventional logic of museums, would have been inconceivable. This is a highly experimental project, the appropriation of a certain content to take it to another plan of action, to degenerate the discourse. A habitual logic in the works I create with alien archives that also reverberate here.

During the selection process I could not stop imagining other completely irreverent ways of acting; to express it with artist’s eyes, I never fully ruled out that this whole final selection could be shown physically in a museum exhibition. To display all these works on walls, as in a classical art gallery, with the three-dimensional works on a large platform. I would like you to imagine that possibility, with all the works packed in a space. It would, without doubt, be a contemporary art exhibition, never more aptly described, compiled with the exhaustive result of an eclectic and transgressive choice.

Locked down eyes also speaks to us, between the lines, of the difficulty of conceiving radical projects that are outside the standard ways, configured over the past few centuries, of exhibiting and re-thinking art collections. Of the possibility of opening up ways of approaching those fantastic collections, to demonstrate, on the other hand, that all the collections of those museums belong to us and we have to be able to shake them up from time to time, even if it is with the irreverence of an appropriationist gleaning.

Jordi Mitjà. Lladó. August 2020.