LUX – Light. From Latin: lux, lucis.

Also: Unit derived from the International System of Units for Illumination or lighting level

Blade Runner, 1982, by Ridley Scott

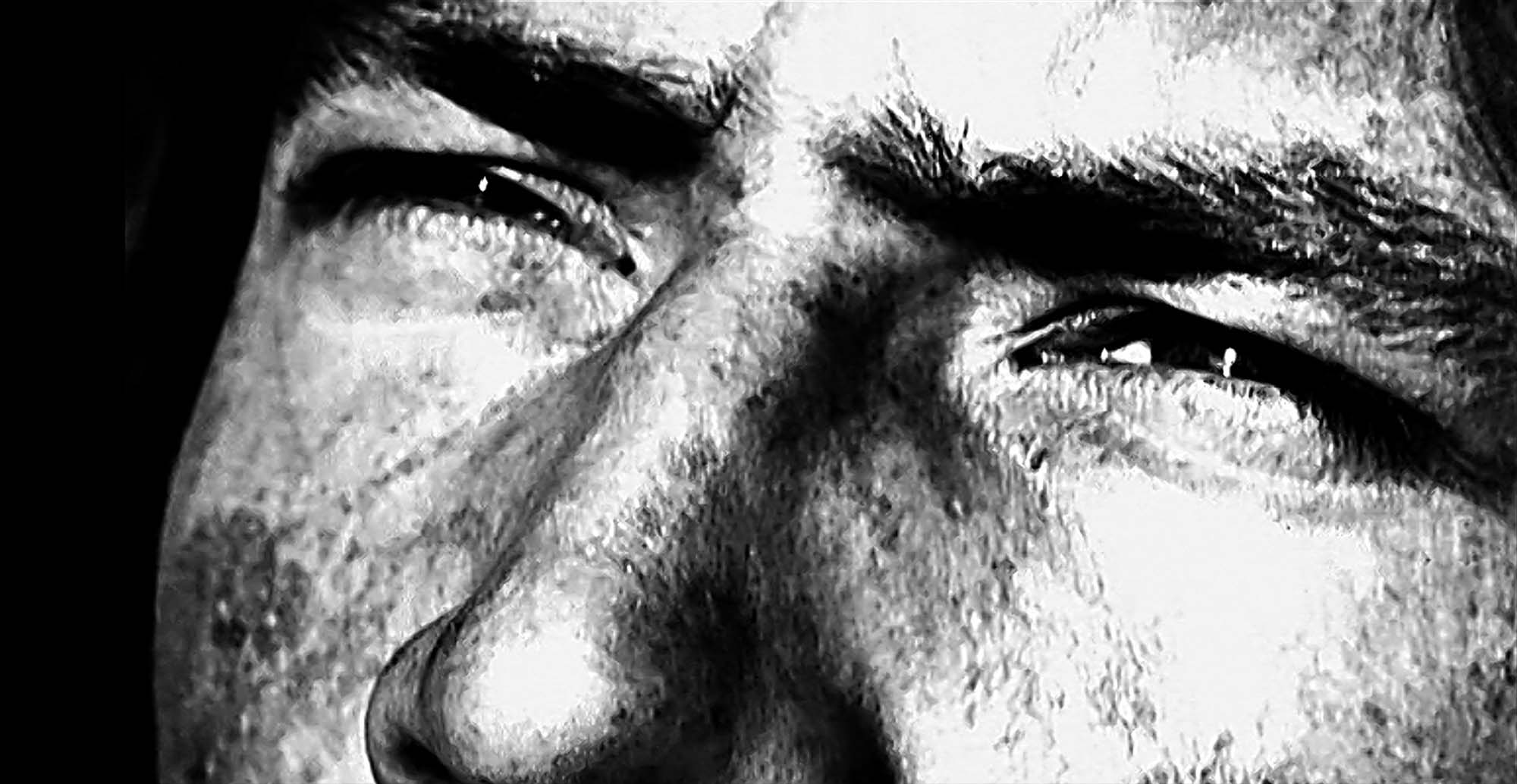

A building’s façade is transformed into a screen that projects an advertising image of a woman taking a pill, featuring Eastern music in the background. The same film, Blade Runner (1982, directed by Ridley Scott), depicts the face of the replicant Roy Batty, split between light and shadow, after the terrible and desperate act of murdering his creator, Tyrell, while the lift starts its metaphorical descent to hell.

Metròpolis, 1927, by Fritz Lang

A scientist tests different devices that generate a circuit of liquids and lights that activate an electric current and a spiral of light giving life to a robot. This robot will lead the workers’ rebellion in the underground ghetto against the dominant powers on the surface

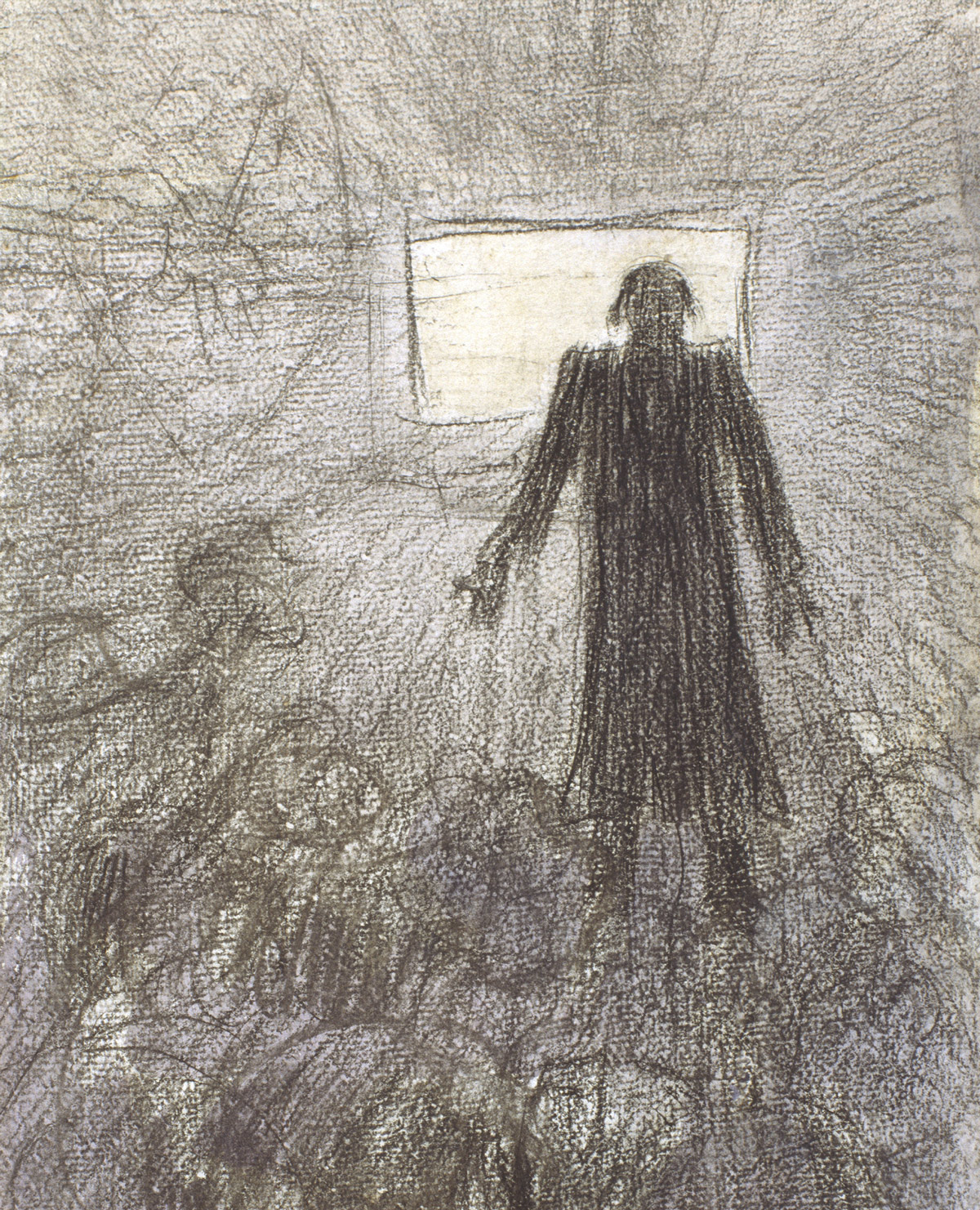

Nosferatu, 1922, by F. W. Murnau

The shadow of Nosferatu’s hands and head are projected over the image of a sleeping girl

The Third Man,1949, directed by Carol Reed

A character, played by Orson Welles, escapes toward the light of Vienna’s sewers/underworld in The Third Man

Barry Lyndon, 1975, Stanley Kubrick

In Barry Lyndon (1975), Stanley Kubrick aimed for the natural light, the light entering through the windows, the fire light from the battles, and the candles inside the house to pictorially illuminate all the scenes that recreate the social ascension and downfall of a man in the 18th century, the century of the Enlightenment.

Caravaggio, 1986, Derek Jarman

High contrast lighting depicts a young Bacchus posing with a fruit basket. Suddenly, he turns, looks at the camera, and bursts into laughter with Caravaggio, the artist (in Derek Jarman’s version, 1986) who is painting the Greek god.

Tron, 1982, Steven Lisberger

In Tron (1982, directed by Steven Lisberger) the characters are kidnapped by rays of laser light and literally enter the video games they are programming.

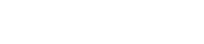

Star Wars. L’Imperi Contraataca, 1980, by Irvin Kershner

Pacing with confidence and dominance, Darth Vader deploys his red lightsabre, starting a duel with Luke Skywalker, who wields the blue lightsabre of the Jedi knights. The forces of good and evil face off in Star Wars. The Empire Strikes Back.

Light in the cinematographic imaginary

Curated by Montse Badia

Art critic and exhibition curator

Fire fascinates us. It is the symbol of passion, destruction, cleansing, anger, power, and transformation.

Fire and its capacity to overcome the dark was discovered in prehistory.

In Greek mythology, fire belonged to the gods until Prometheus stole it and gave the gift to humankind.

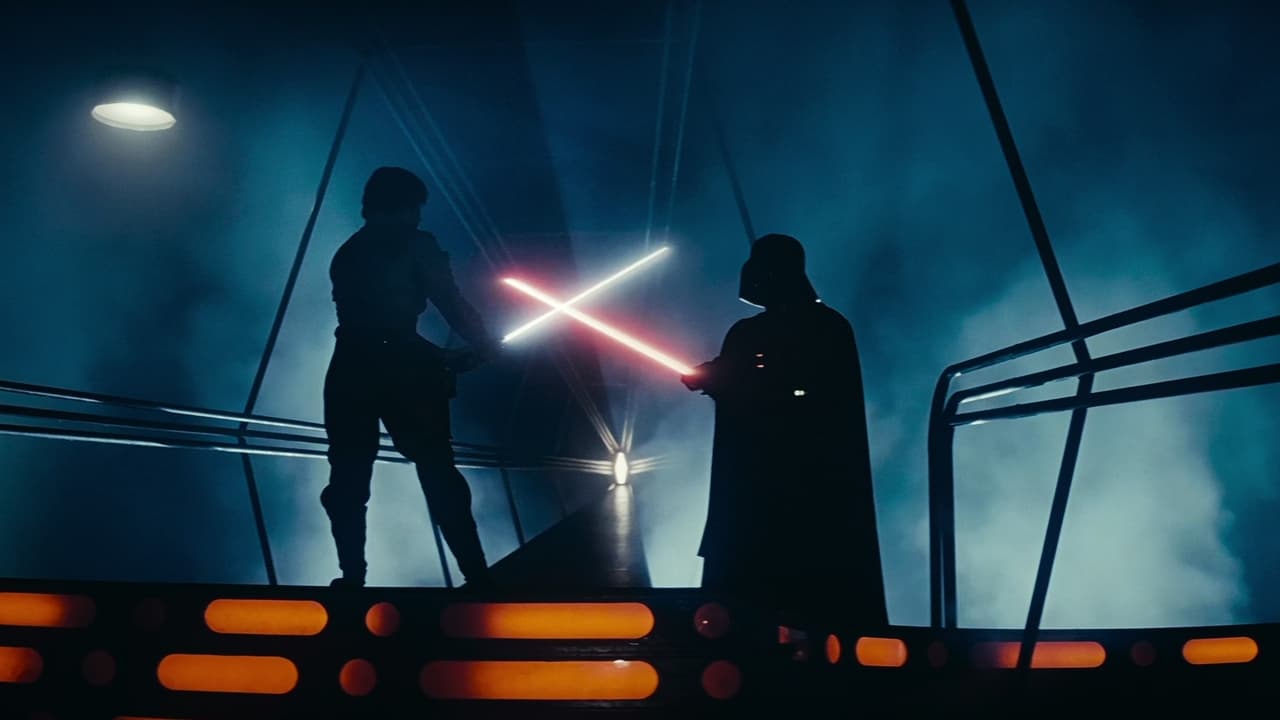

This symbolism is still with us today, and we’re reminded of it every four years during the celebration of the Olympic Games.

In Barcelona, we have a great example with the Olympic Torch designed by André Ricard.

André Ricard Sala. Olympic Torch, Barcelona’92. Barcelona, 1992. Reference: MADB 135880. Museu del Disseny-Dhub. Photography: Estudio Rafael Vargas

Untitled (Foc de Sant Joan. Photograph for the book “Això també és Barcelona” by Josep Mª Espinàs), circa 1965. Photography. Gelatin bromide on silver. Long-term loan by the artist Oriol Maspons, 2011. © Arxiu Oriol Maspons, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2019. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Gordon Matta-Clark. Fire child, 1971. Super 8 mm film transferred to video, colour, no sound, 9 min. 47 s. R.2963, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. © Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, VEGAP, Barcelona. Photography: Tony Coll.

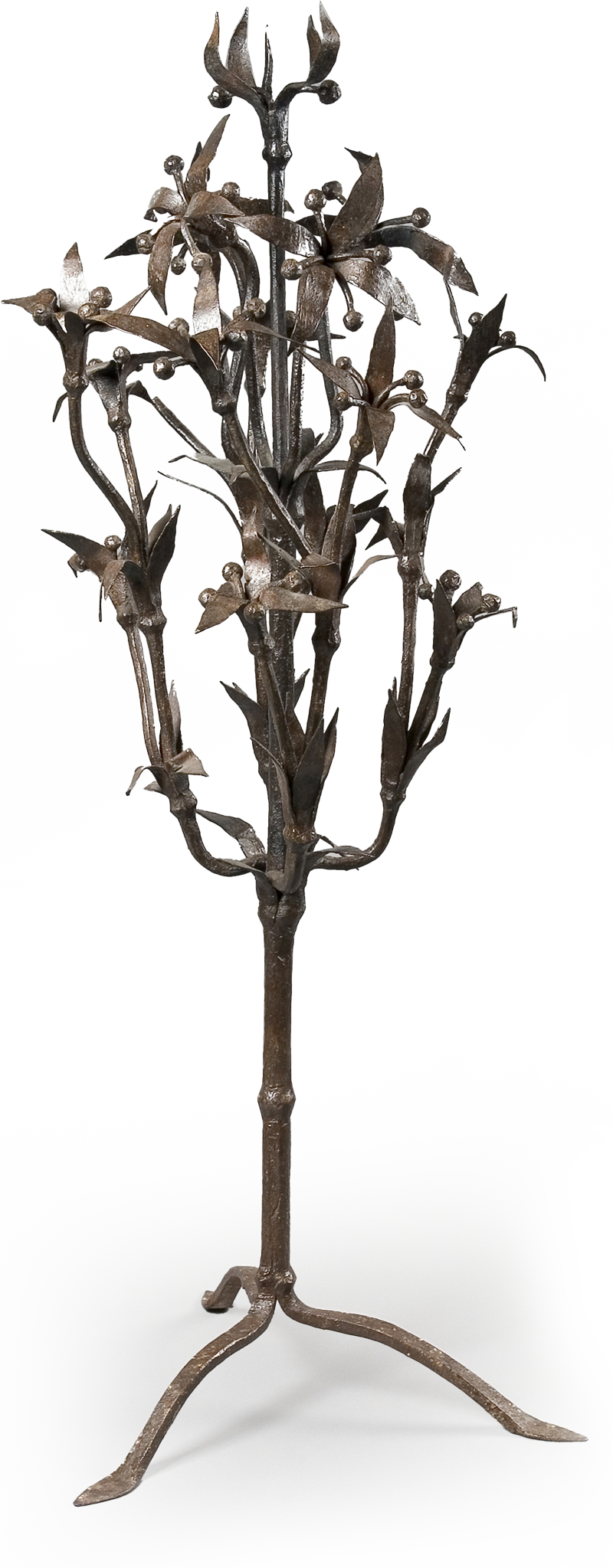

Other contemporary artists include fire from other perspectives. For example, we can look at Matches, the public sculpture by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen located in Vall d’Hebron, in front of the Pavilion of the Republic. The MACBA also features a model of this sculpture. Coosje van Bruggen explained it like this in 2006: “It’s just a burning match, like a lighthouse, with the outline transforming into a lance or plume of fire, reminiscent of the words of Cervantes’s Don Quixote de la Mancha: ‘We may see that the lance has never blunted the pen, nor the pen the lance.’ Over time, matchbooks, like liquid erasers for typewriters, have become an archetypal object on the verge of disappearing, subjected to a telescopic perspective that shifts from the intimate and emotional handheld object to the large-scale, autonomous, and almost abstract project, with an architectural structure and proportions.”

Claes Oldenburg – Coosje van Bruggen. Matches, 1992. Painting on cardboard, metal, and wood, 14.5 x 13.5 x 10 cm. R.0817, MACBA Collection. Long-term loan by the Ajuntament de Barcelona. © Claes Oldenburg © Coosje van Bruggen. Photography: Gasull

Fina Miralles has carried out a series of actions to explore the connections between the human body and different materials, for example the series of artworks The Body’s Relationship with Natural Elements in Everyday Actions (1975) and more concretely in Relationships. The Body’s Relationship with Fire. Lighting a Fire (1975/2020).

Fina Miralles. Relationships. The Body’s Relationship with Fire. Lighting a Fire, 1975/2020. Inkjet printing on paper. 2 photographs, 42 x 42 cm each. R.5883, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Donation by the artist. © Fina Miralles.

Grup de Treball. Collective Film, 1974. 16 mm film transferred to video, b/w, no sound, 42 min. R.1466, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Donation by Grup de Treball. © Grup de Treball. Photography: Rocco Ricci

“Burst of heat and light

produced after a body combusts”

Joan Brossa. Fire. In: Ollaó!, 1975. 28.7 x 14 cm. Sheet 14 of a gallery proof from the 1989 edition (Barcelona: Alta Fulla). R. A.JBR.00498.108. MACBA Collection. Research and Documentation Centre. Joan Brossa Fund. Long-term loan by Fundació Joan Brossa

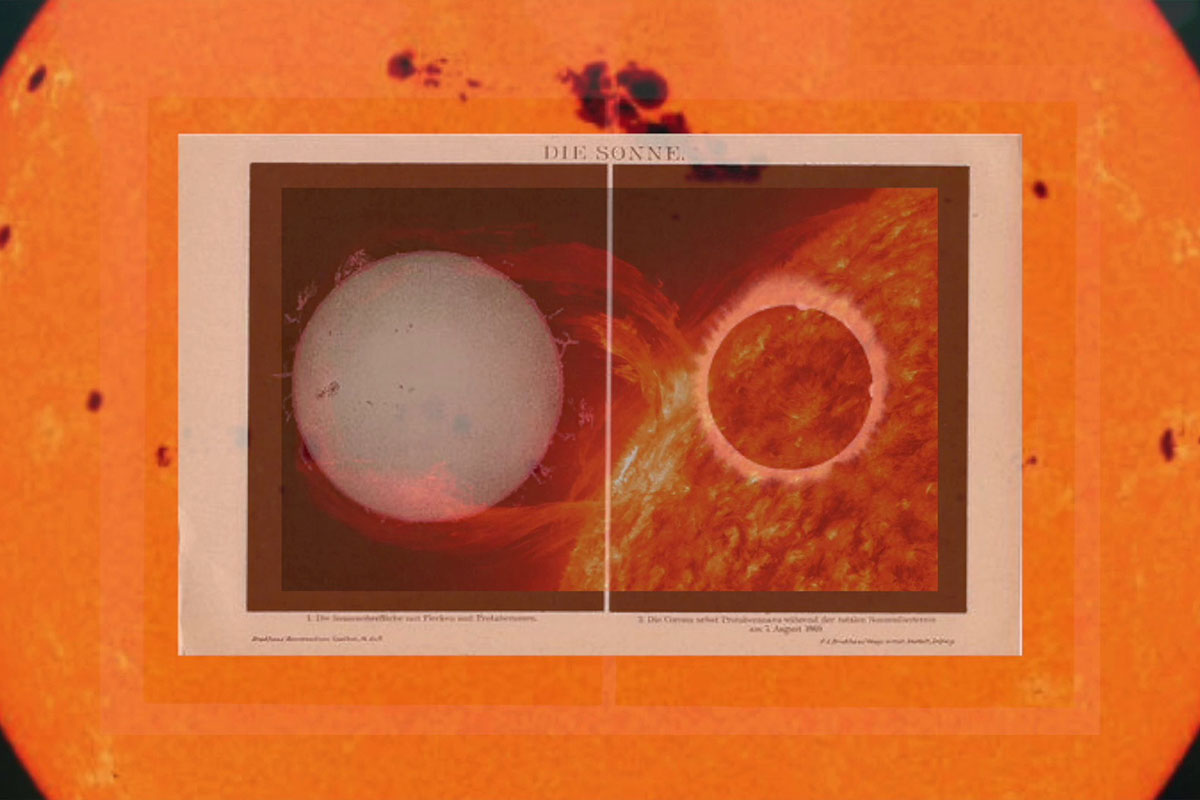

The sun, our most powerful source of light, was a god in many cultures, and some countries include it on their currency. The back sides of the Cuban ten and twenty cent coins feature a five-pointed sun with rays of light.

Republic of Cuba, 10 cent coin, 1949. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya; donation by Arturo Godó, 2018. Public domain. Public domain

República de Cuba, moneda de 20 cèntims, 1948. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya; donació d’Arturo Godó, 2018. Domini públic.

The sun is also a reference to measure time.

Sundial. Europe, early 20th century. MADB 135.0001. Museu del Disseny-Dhub. Photography: CRBMC_Roser Casas.

At the entrance to the Museu de Cerdanyola, Tom Carr installed Sun, with 69 laminated colour glass discs that reproduced the score of Ad Libitum by Jesús Acebedo.

TCteamwork: Tom Carr – Lidia Carrera – Xema Vidal. Sun, 2022. Installation. 69 laminated coloured glass discs. Sun reproduces the musical composition Ad Libitum by Jesús Acebedo. Produced by: Amics del Museu de Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Day and night

Night, darkness, is associated with the unknown, danger, just like the 19th century allegories remind us, representing the victory of day over night.

Antoni Caba Casamitjana. The Triumph of Day over Night Preceded by Dawn, 1882. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Adquisició, 1992; domini públic.

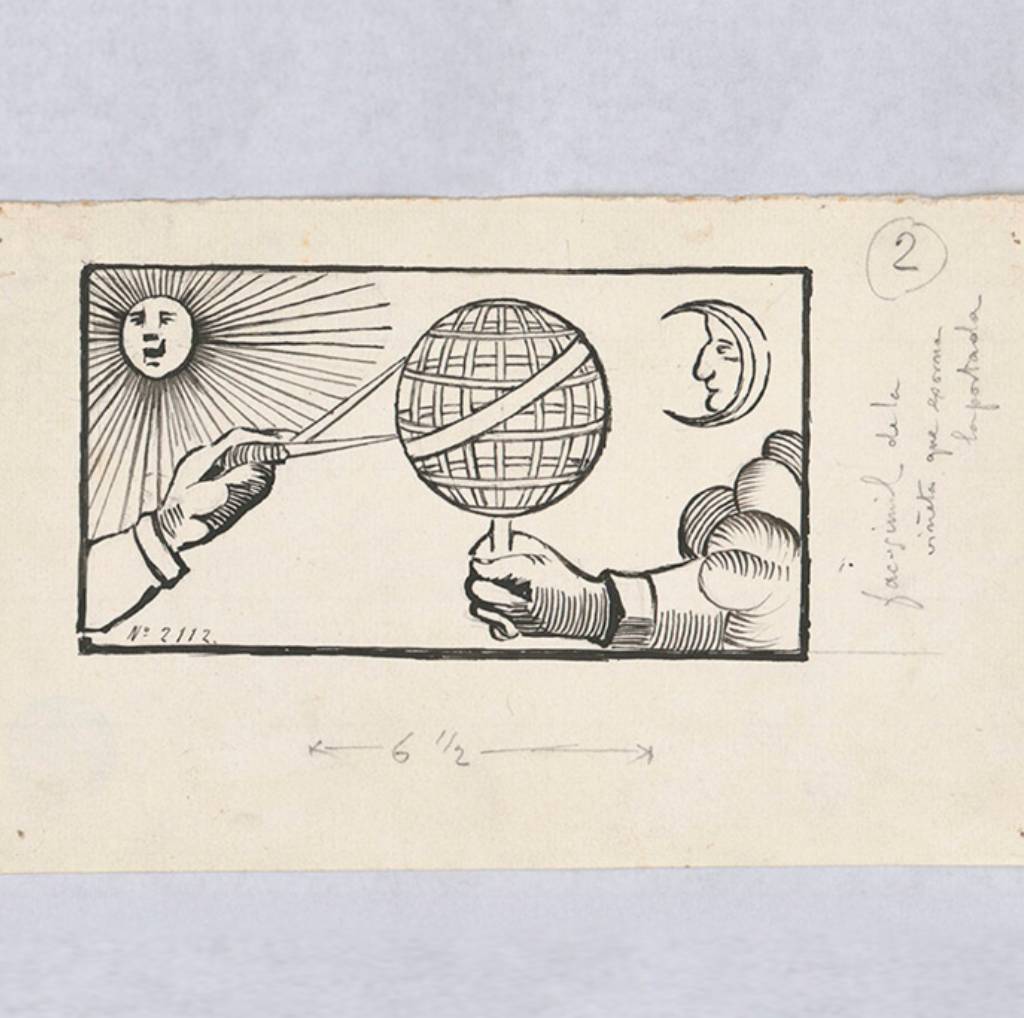

The sun and moon are personified in a more naïve fashion in this drawing by Josep Lluís Pellicer.

Josep Lluís Pellicer Fenyé. Vignette with the sun and the moon, second half of the 19th century. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquisition from the Casellas collection, 1911. Public domain

They were also represented with nearly Brossian irony by Perejaume.

Perejaume. [The Moon], undated. Metal, plastic, and paper, 8 x 8 x 0.3 cm. R.4787, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Joan Brossa Fund. Long-term loan by Fundació Joan Brossa. © Perejaume, VEGAP, Barcelona

The immensity of the sea and the dramatic nature of the sky upon which the moonlight is reflected were painted by Antoni Fabrés at the end of the 19th century.

Antoni Fabrés Costa. Nit de lluna sobre el mar, cap a 1880. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Donated by the artist, 1925; public domain

A work that enters into dialogue with Nocturnos by Mercedes Mangrané.

Mercedes Mangrané. Nocturnos, 2014. Oil on canvas, 22 x 27 cm. MORERA Collection. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida. Acquisition, IX Biennal Leandre Cristòfol, 2015.

Evenings are also the time for reflection. Modest Urgell painted landscapes full of an almost Nordic melancholy.

Modest Urgell Inglada. Evening, circa 1875-1900. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Contribution from the Diputació de Barcelona, 1906. Public domain.

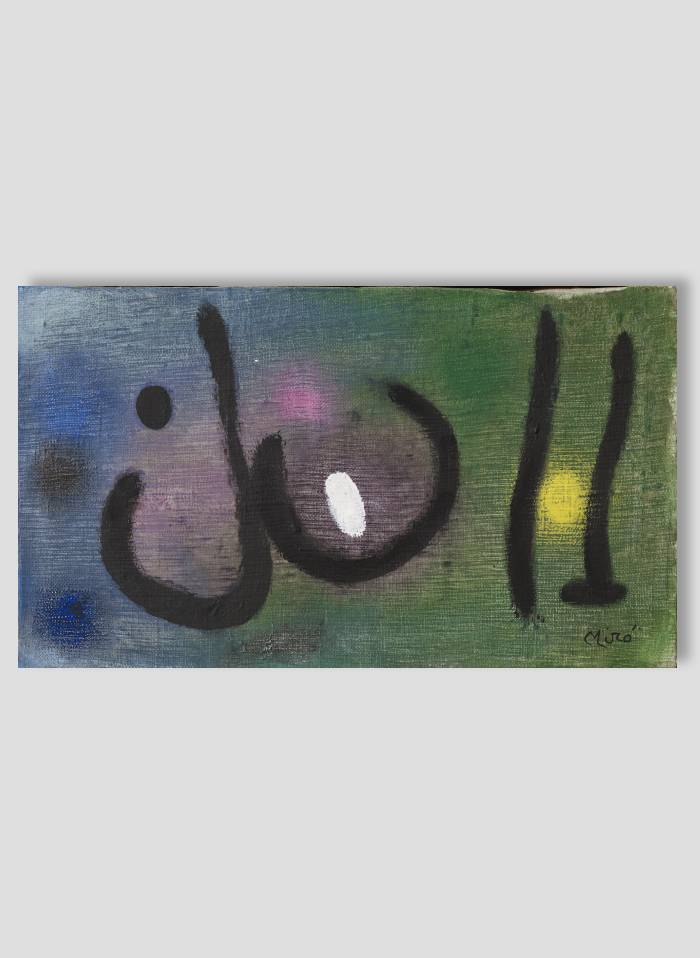

Meanwhile, Joan Miró painted music.

Joan Miró. Music of the Twilight 5, 1966. Oil on canvas, 19 x 33 cm. FJM 4696. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2024.

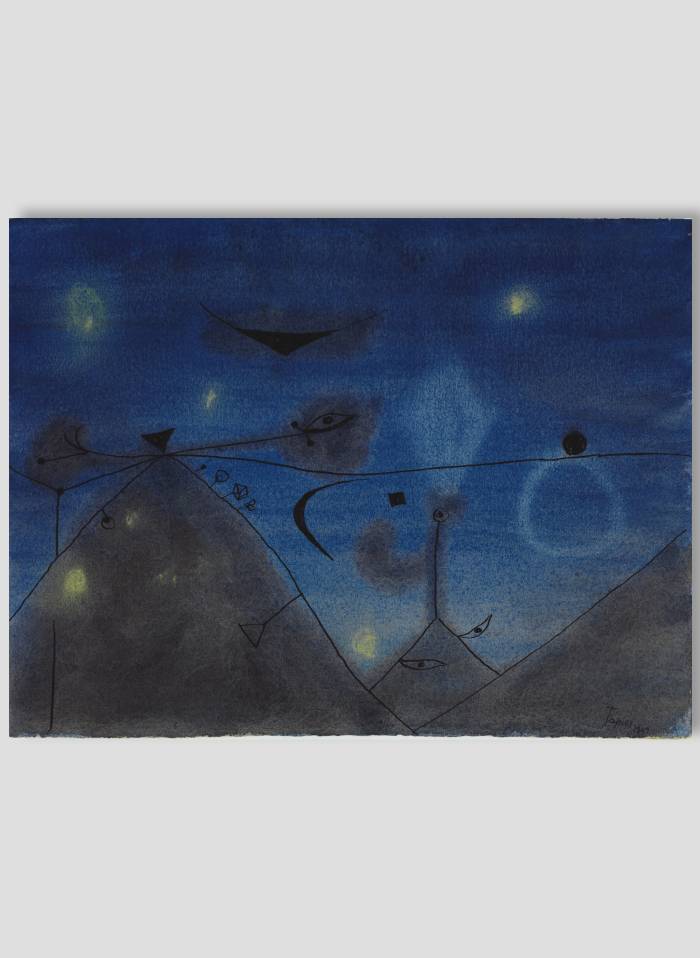

The artists of Dau al Set, heirs of Surrealism, created scenes replete with references to magic and fantastic worlds, including the discomforting nocturnal landscapes by Tàpies and the fantastic and disturbing scenes by Joan Ponç, the nighttime artist par excellence.

Antoni Tàpies. (Untitled), 1949. Watercolour, Chinese ink, and pastel on paper, 18.8 x 25 cm. R.4680, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Joan Brossa Fund. Long-term loan by the Ajuntament de Barcelona. © Comissió Tàpies, VEGAP, Barcelona.

Joan Ponç Bonet. Night Trip, No. 1, 1982. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Legacy of Manuel Maria Bosch Puig, 2016. Joan Ponç, VEGAP, Barcelona, current year.

Fiat Lux

For millennia, many religions have referred to light and its polar opposite, darkness, as an element with a mythical and archetypal character. The highest calling of Buddhism is to reach the light or satori. Starting in the 1st century C.E., the Catholic Church transformed light into a metaphysical element linked to the truth infused by God. In Islam, Allah is the light from the heavens and the earth. Light plays a central role in Jewish liturgy. Torches, candles, lamps, and candelabras are included in ceremonies in numerous religions. In fact, religious ceremonies often begin the moment when the candles and lamps are lit.

Candelabra, 15th century. Iron. From Sant Vicenç de Rus (Castellar de n’Hug, el Berguedà). Inventory number MDCS 640. Museu Diocesà i Comarcal de Solsona.

Unknown. Lamp or crown of light, 12-13th century. Museu d’Art de Girona, reg. no. 131.558. 131.558. Diputació de Girona Fund. Photography: Rafel Bosch.

Oil lamp, 19th century. 23.5 x 9.5 x 9.5 cm. Ref. MFM 14444. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero.

19th century lamp with a religious motif (ref. 2556). Museu de Granollers.

Younès Rahmoun. 77, 2014. Light installation. Variable dimensions. R.5248 MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Work acquired thanks to the Fundació Banc Sabadell. © Younès Rahmoun.

Jordi Benito. Seat (The seat of God). Installation, 2005. © Jordi Benito. VEGAP, Museu de Granollers.

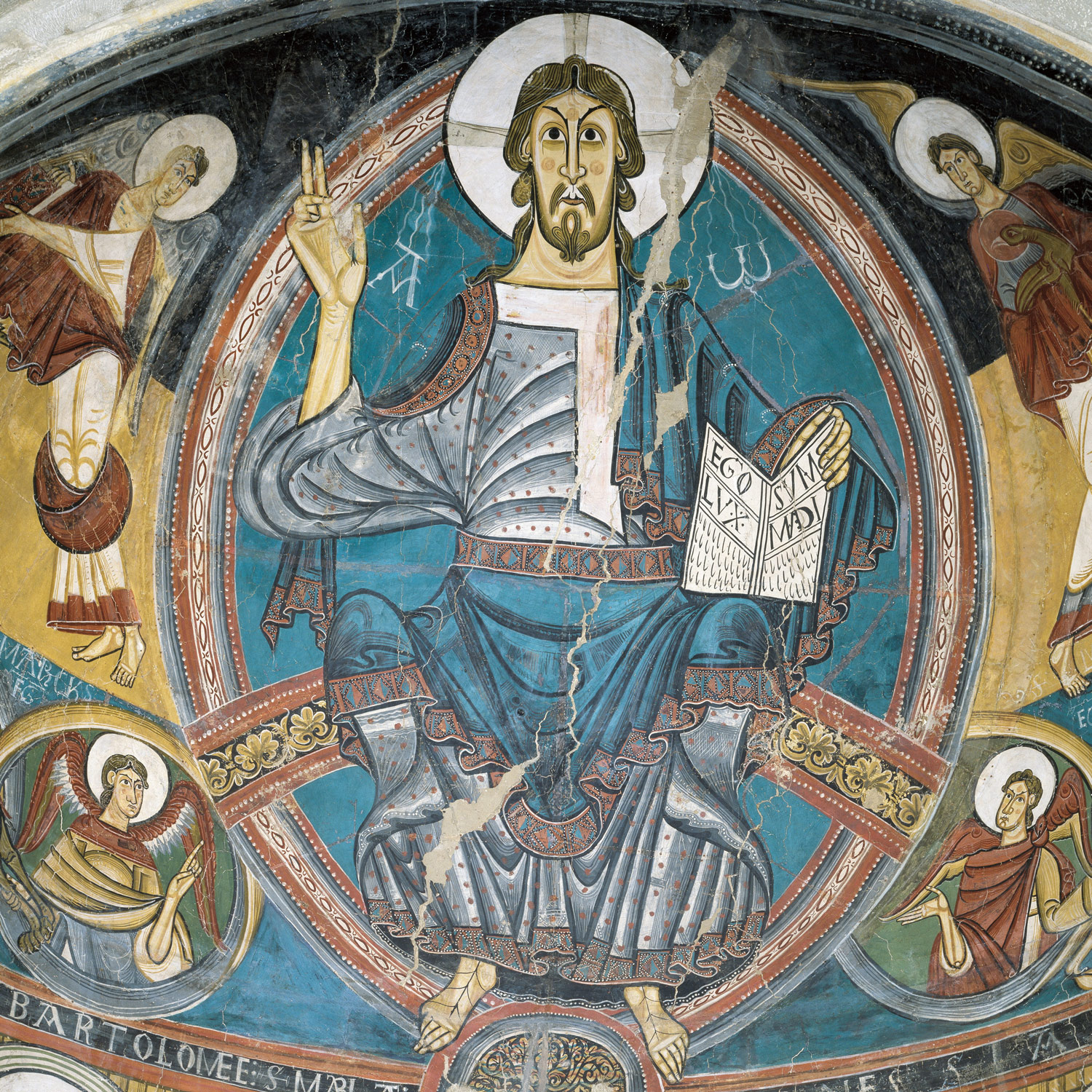

The Christ in Majesty in Sant Climent de Taüll, one of the most iconic works from the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, holds a book in his left hand with the inscription “EGO SUM LUX MUNDI” in reference to the Gospel of Saint John: “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life”. Light is the verb, the word that gives life, and it is the beginning of everything.

Master of Taüll. Apse of Sant Climent de Taüll, circa 1123. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquisition from Junta de Museus in the 1919-1923 campaign. Public domain

We also find this reference indirectly in a lamp housed at the Museu d’Art Medieval. The surface of this oil lamp is decorated with enamels that depict lily of the valley stems and which also feature the monogram of Christ, “IHS” within a flaming circle.

Lamp. First third of the 17th century. 7.4 x 9.1 x 7.6 cm. © Museu Episcopal de Vic.

Sunlight is also a key element in monstrances, pieces made of gold and other precious materials intended to display the sacred host to the faithful. The host is placed between two pieces of glass within the monstrance that represents the sun with a ray of silver and precious stones. An excellent example is the monstrance by Alfons Serrahima that we find in the Museu d’Art de Girona.

Alfons Serrahima i Bofill. Monstrance, 1951. Museu d’Art de Girona; reg. no. MDG2713. Bishopric of Girona Fund. Photography: Rafel Bosch.

The sculpture of Buddha Amitayus kept in the Biblioteca Museu Victor Balaguer, which was probably made between 1700 and 1799, reminds us of the symbolism of light within Buddhism as an element of transformation and self-awareness. The sculpture arrived at the Biblioteca Museu through Juan Mencarini, sent as the consul to Singapore and Hong Kong and who travelled to Barcelona as a representative of the island of Formosa during the 1888 Universal Exposition.

Buddha Amitayus, 1700-1799. Sculpture, 65 x 38.5 x 30.5 cm. Reference BMVB-1283. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer

At the Museum de Granollers we can also find the sculpture of the goddess Guan Yin from the era of the Ming Dynasty, a figure venerated by Buddhism and who is related to compassion.

Figure of the goddess Guan Yin. Ming Dynasty. Sculpture, 18th century. Reference 3091. Museu de Granollers.

Carlo Giuseppe Ratti. Adoration of the Shepherds, 1773. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Long-term loan from the Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi, 1902; added in 1906. Public domain.

Joan Sanxes Galindo. Altarpiece of the Rosary: Assumption of the Virgin Mary, 1603. Museu d'Art de Girona; reg. no. MDG0361-4. Bishopric of Girona Fund. Photography: Rafel Bosch.

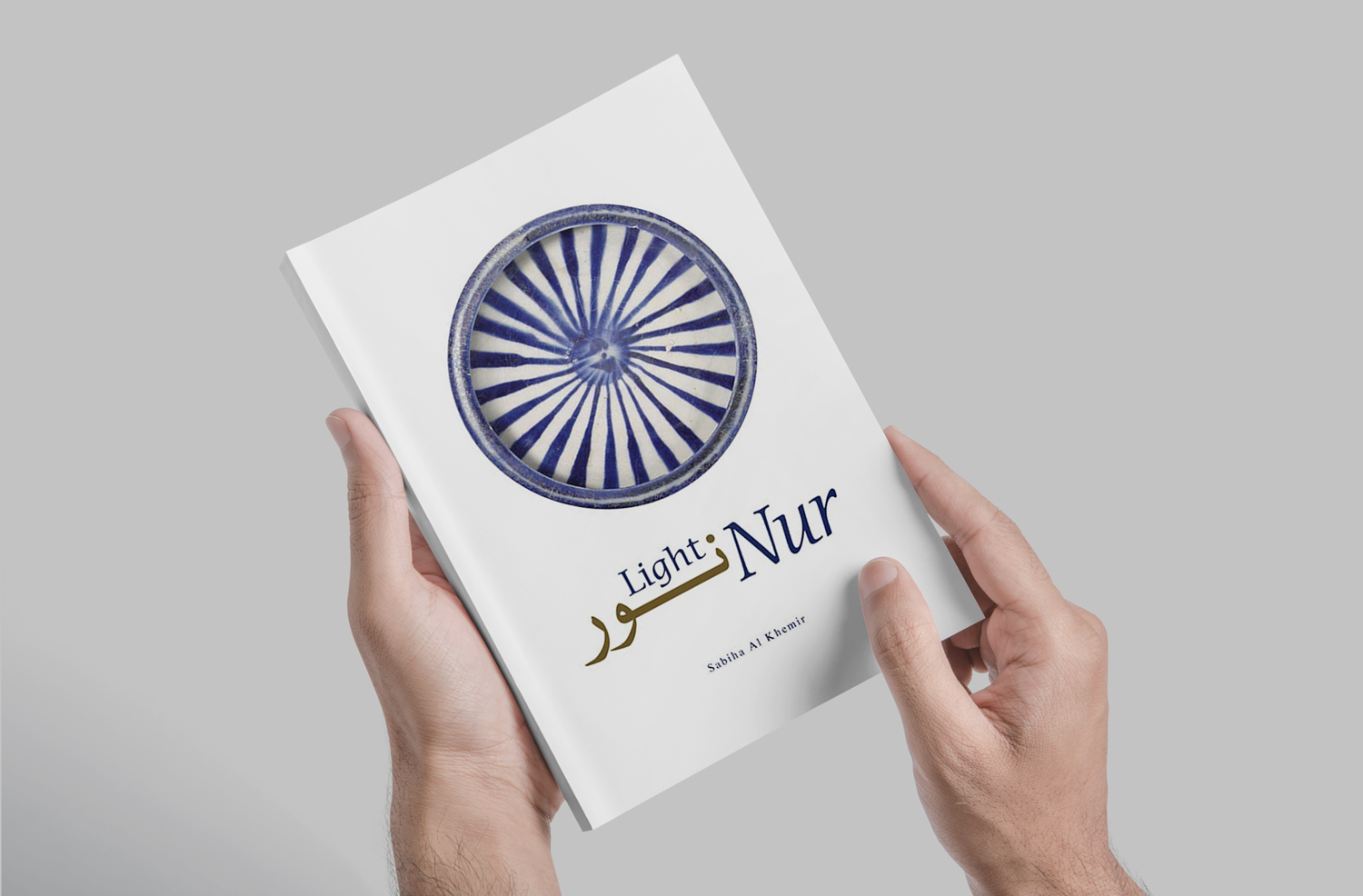

In the library of the Museu Nacional, the book Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World (2013) by Sabiha Al Khemir emphasises how light is a shared and unifying metaphor among the Muslim, Christian and Jewish religions. The book includes manuscripts illustrated with golden pigments and also objects related to scientific thought, such as sundials and astrolabes.

Apparitions / Projections

Between the material and the immaterial, between faith, magic, technology, science, and art, apparitions/projections imply the possibility of amplifying presences and images, of mixing them in space, without boundaries or limits.

Josep Benlliure Gil. L’aparició, 1876. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Legacy of Camil Fabra, marquès d’Alella, 1902. Public domain

However, not all projections/apparitions are positive. In Leonardo Alenza’s painting The Limping Devil. Apparition (1838), this figure is depicted somewhere between awkward and mischievous.

Leonardo Alenza Nieto. The Limping Devil. Apparition , 1838. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquisition, 1943. Public domain.

Projections can also symbolise a specific personal and contextual situation.

Albert Bayona. Summer night. Projection for a confined space, 2010. Single-channel video installation, colour, 3h (loop). MORERA Collection. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida. Donation by Albert Bayona, 2013

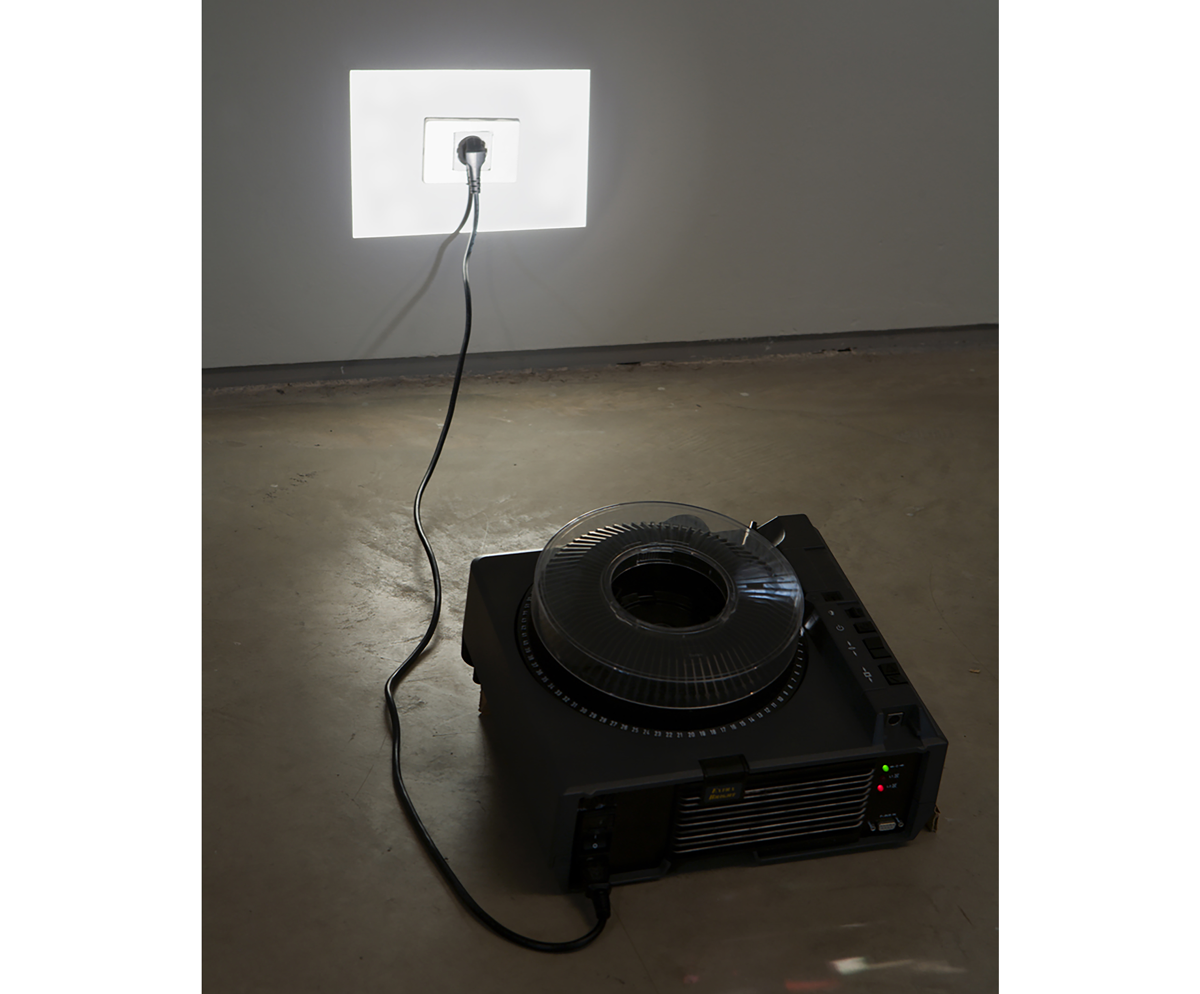

They can also provide evidence of the mechanisms behind the process, as is the case of Projectedsocket by Luis Bisbe. This piece involves a socket that has an image of itself projected onto it from the projector to which the socket provides power. It is crafted in a way that the image fits perfectly over the object, including the cable, making it nearly invisible.

Luis Bisbe. Projectedsocket, 2001. Slide and slide projector, 20 x 25 x 120 cm. R.6730. MACBA Collection. Long-term loan by the Ajuntament de Barcelona. © Luis Bisbe, VEGAP, Barcelona.

Projected shadows

The mechanisms and power of representing projected shadows are also a subject of artistic exploration.

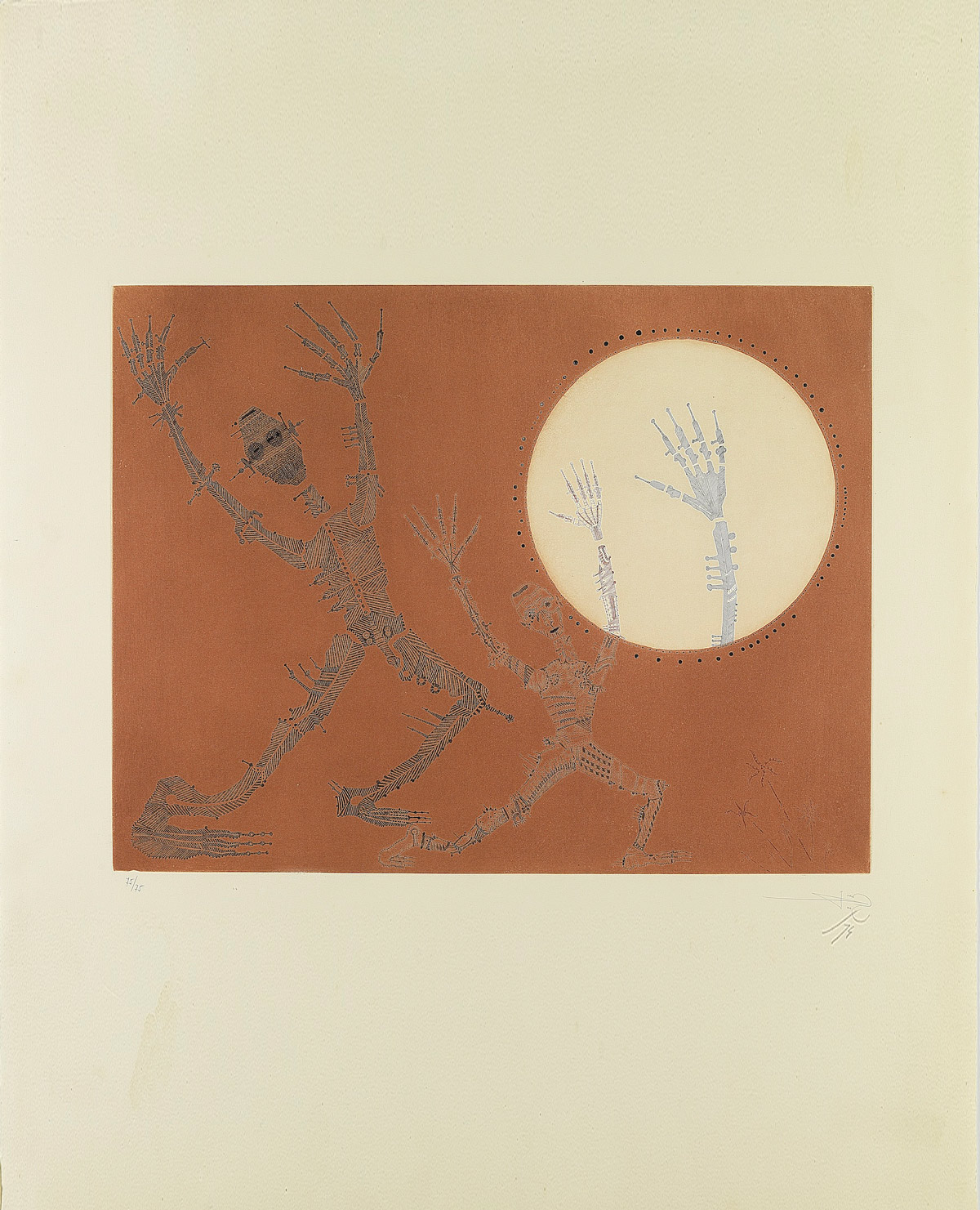

Joan Ponç. Moon Shadow, 1973. Etching on paper, 71.2 x 82.4 cm. R.1162, MACBA Collection. Long-term loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya. National Art Collection. © Joan Ponç, VEGAP, Barcelona. Photography: Tony Coll.

Ramon Casas Carbó. Chinese Shadows, c. 1897. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquisition, 1992. Public domain

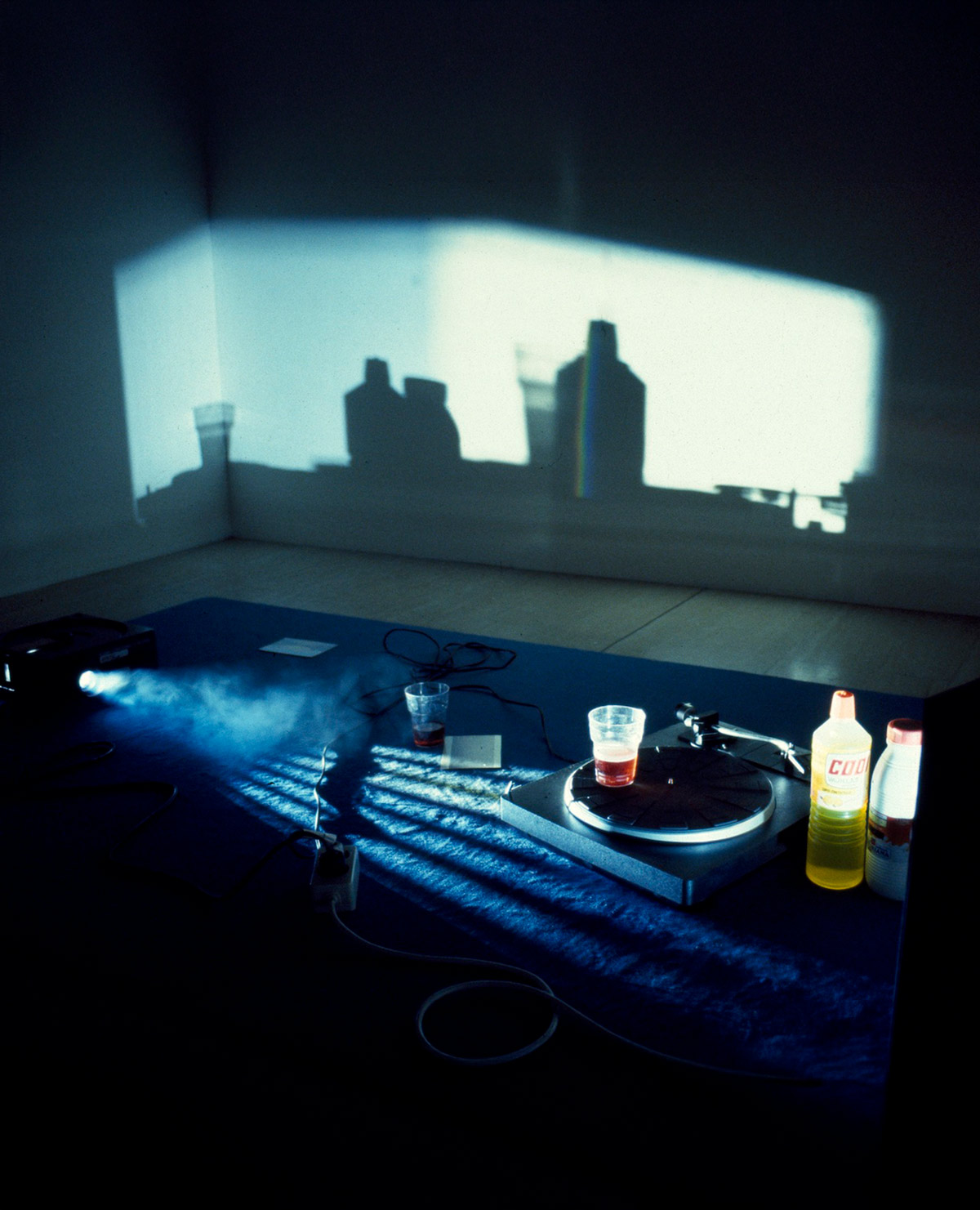

Eulàlia Valldosera. Love's Sweeter than wine. Three Stages in a Relationship. Series: “Appearances” #3, 1993. Light installation. Variable dimensions. R.4440, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Long-term loan by the artist. © Eulàlia Valldosera, VEGAP, Barcelona.

We cannot overlook their symbolic and evocative power.

Light and shadow as projected by the religious, expertly captured by the photographer Antoni Campañà, bring us back to the 1930s, right before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and remind us of the Church's interested role in this conflict.

Theatre and religion, stained-glass windows and scenography

The amplifying effect of light from stained glass has been a resource used by religion, emphasising its theatrical and performative facets.

Joan Busquets Jané, Josep Pey Farriol (drawing of the angels and paintings of the willows). Stained glass from the Cendoya Chapel, 1905. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Donació de la família Cendoya, 1973. © The author or their heirs.

At the Museu de Cerdanyola we can find the Modernist stained-glass windows from the López Tower by Eduard Maria Balcells.

Eduard Maria Balcells. Sliding door of the gallery of the López Tower, original location, Barcelona, c. 1906. 1906. Carpentry and leaded stained-glass window decorated with acid, cathedral glass, and Florentine printed glass. Long-term loan by Montserrat, Maria Isabel, Carles, Ricard, and Blanca Domènech Sagué. Museu de Cerdanyola.

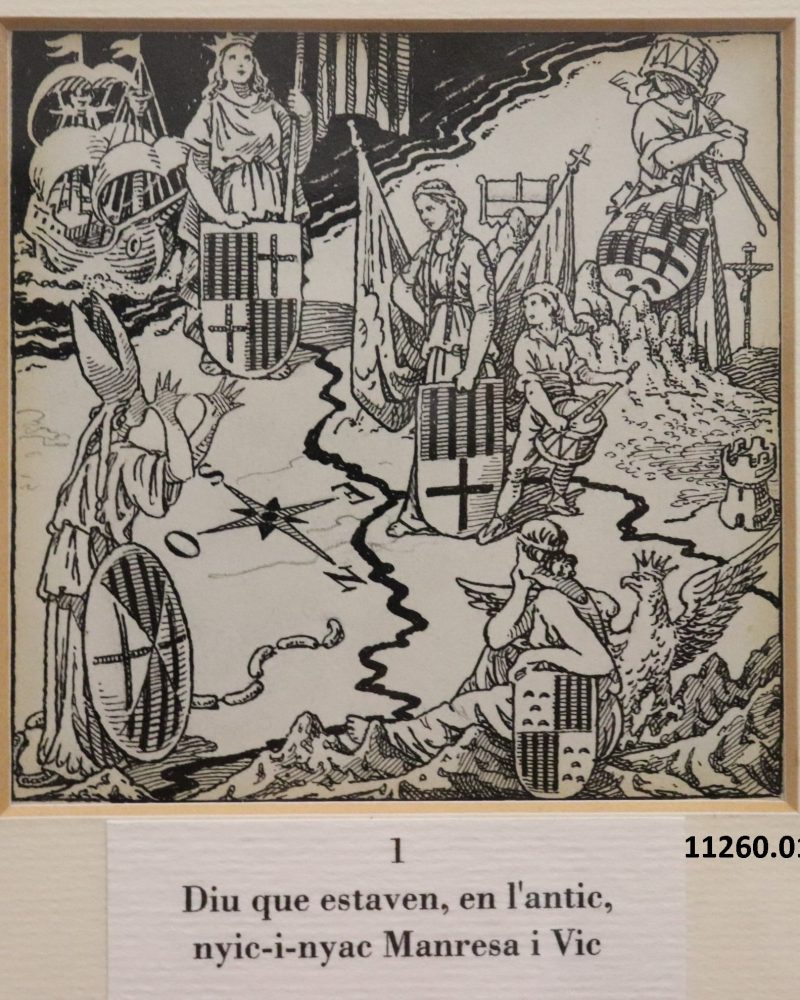

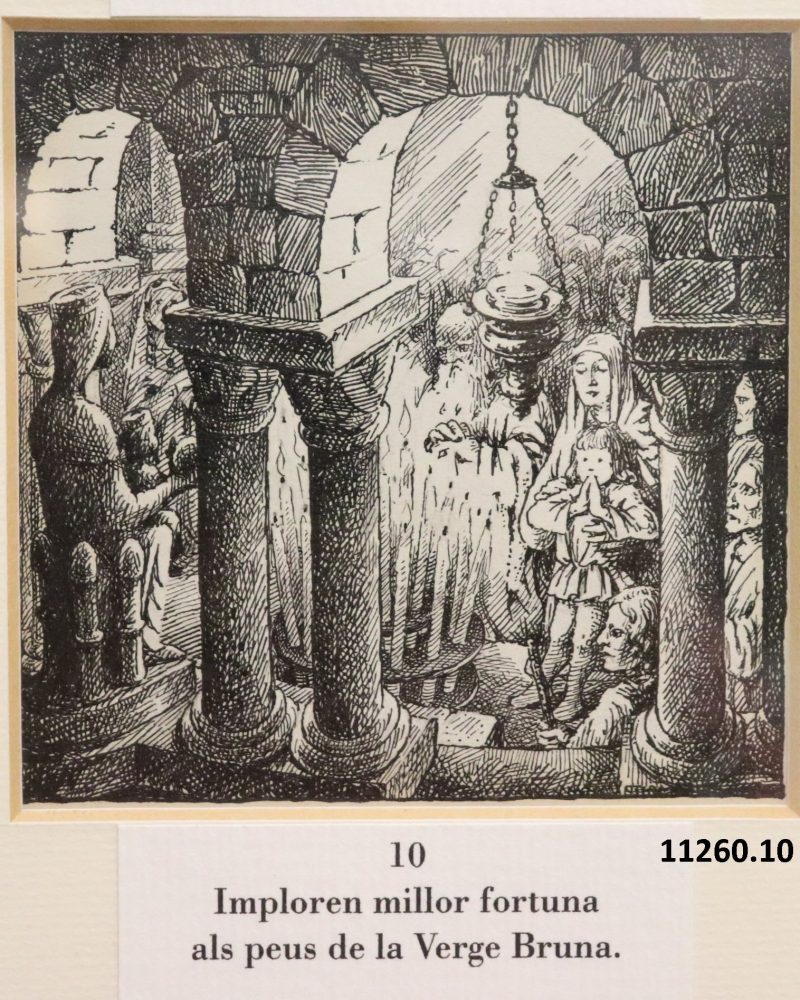

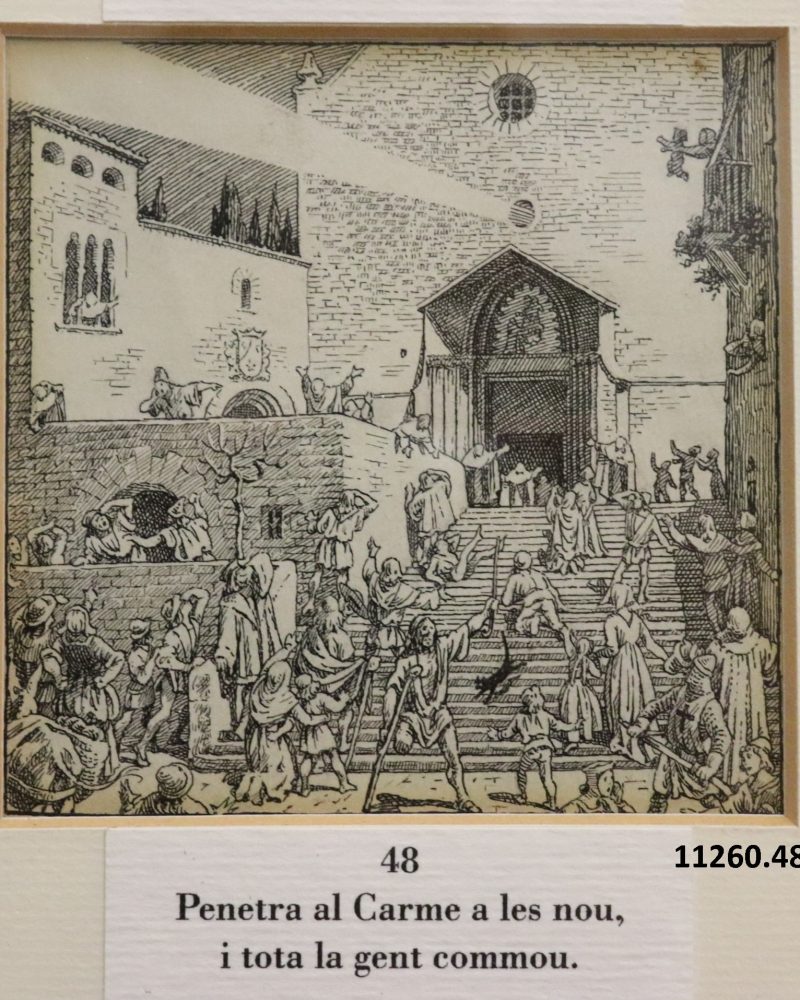

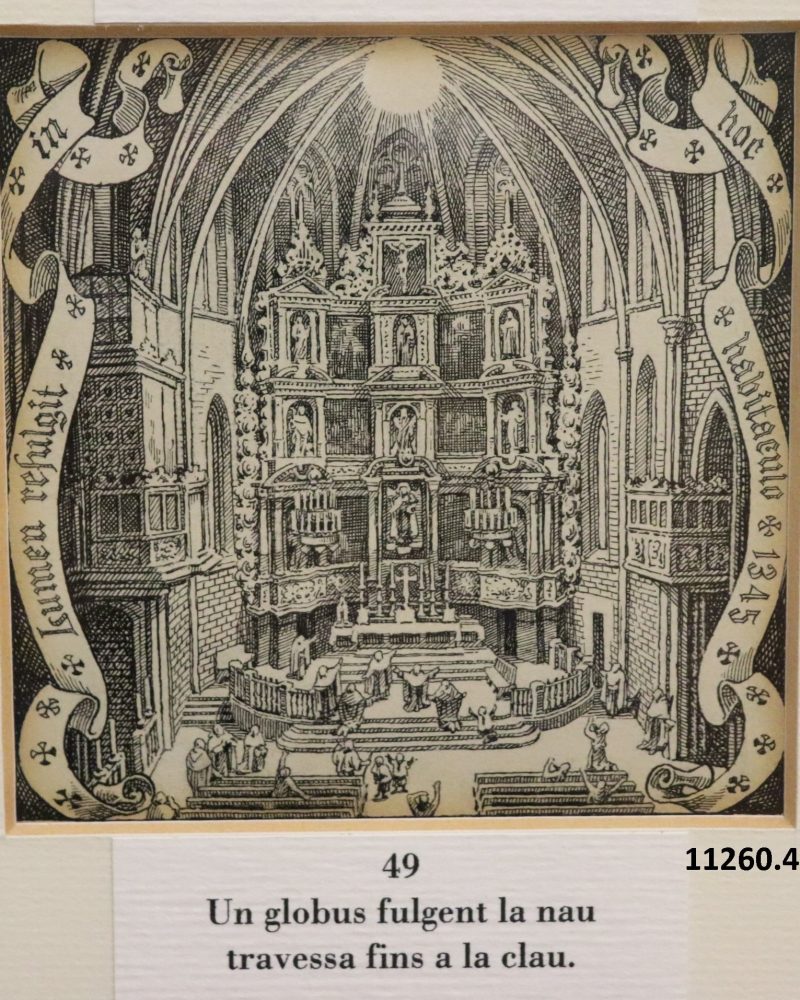

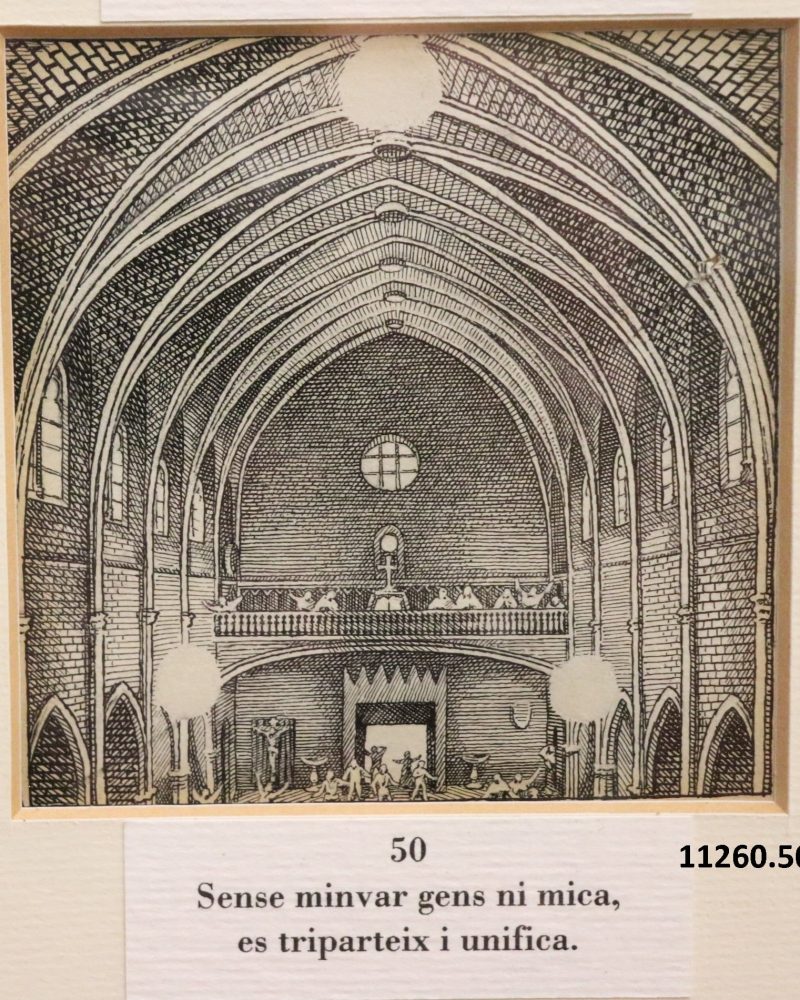

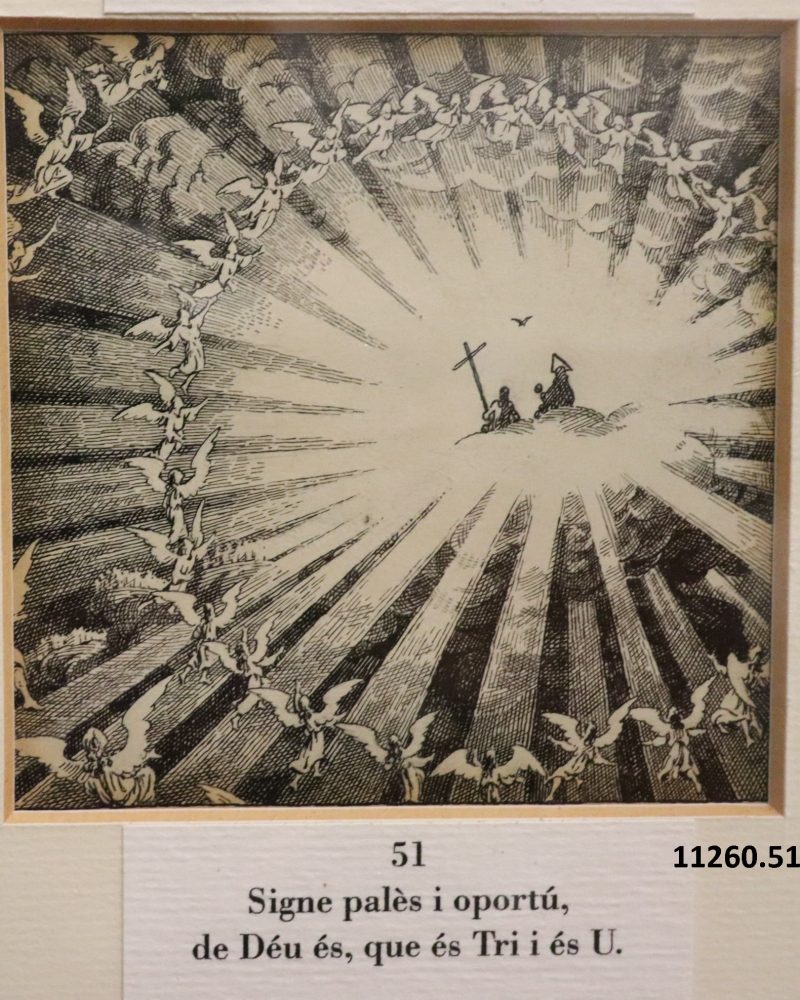

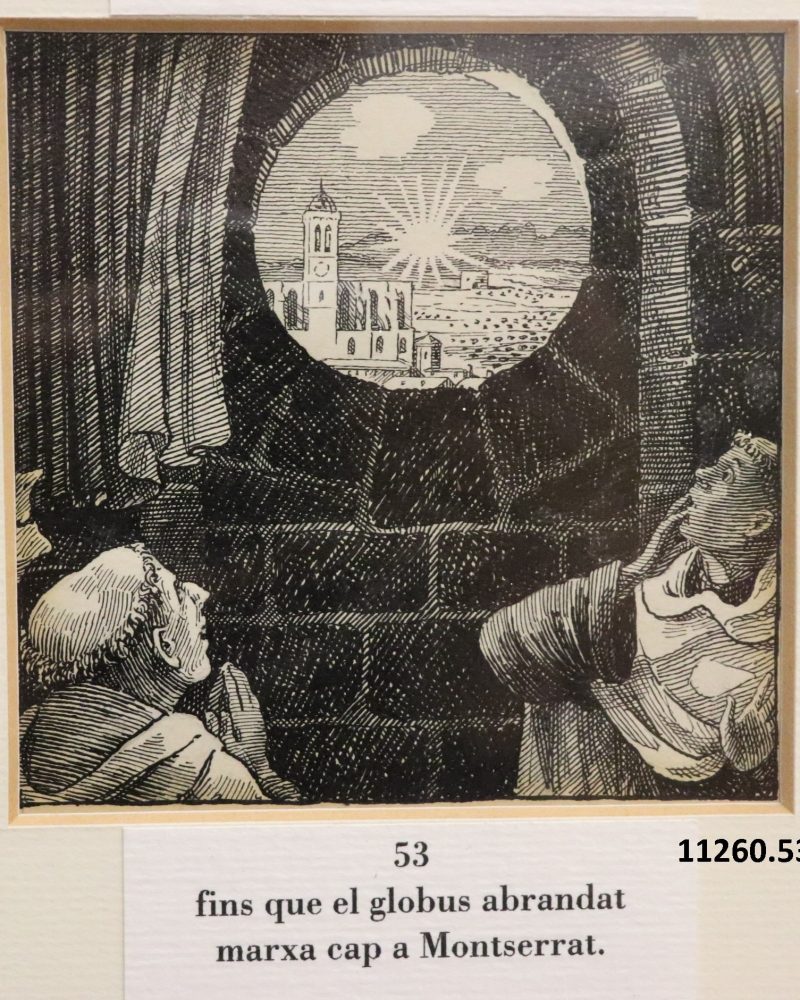

While stained-glass windows boast an element of theatricalityAuca de la Llum seems to be a sort of storyboard made up of 87 vignettes preserved in 3 squares. They are accompanied by couplets written by Ramon Albareda i Garriga. The Auca de la Llum is a prime example of the formation of a certain imagery from the city of Manresa in the first years of the second half of the 20th century. Each vignette is a compendium of references to historic events and figures, and to the local stories and folklore of Manresa.

Joan Vilanova i Roset Auca de la Llum, 1953-1959. Ink on paper. MCM11260. Museu de Manresa

The Age of Enlightenment (the name of which, in other languages, also alludes directly to the idea of light: Lumières, Era de la Il·lustració, Illuminismo, Aufklärung), represents a journey from dark to light, from knowledge based on superstition to a rational and scientific approach which is applied both to religion as well as to topics related to society, politics, and economics. Rather than faith, reason is the main guarantor with the authority to legitimate the ideals of freedom, progress, tolerance, fraternity, the notion of a constitutional government, and the separation of Church and State. Knowledge is understood as a tool for liberation, as a way to escape from the darkness of Plato’s cave. Light becomes a symbol of knowledge and wisdom. Diderot’s Encyclopédie is a clear example of the Enlightenment. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, philosophers were able to spread their ideas from scientific academies, literary salons, dictionaries, encyclopaedias, books, and pamphlets. This was the time when the book and publishing industry started to expand, and science became popularised. The arts (especially music) and culture in general flourished based on the widespread emphasis on the need to learn and be cultured.

On the sgraffiti on the Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer we can find clear references to masonry, to which Víctor Balaguer belonged. The eagerness to dispel fears and darkness through the lights of reason connects both movements.

One of the most notable elements of the Enlightenment is the activity in the “public sphere”, a space for communications that can host different spheres of more open debate. The Enlightenment also opened up more accessible public spaces, more intense social exchanges, and also spurred a burgeoning print culture.

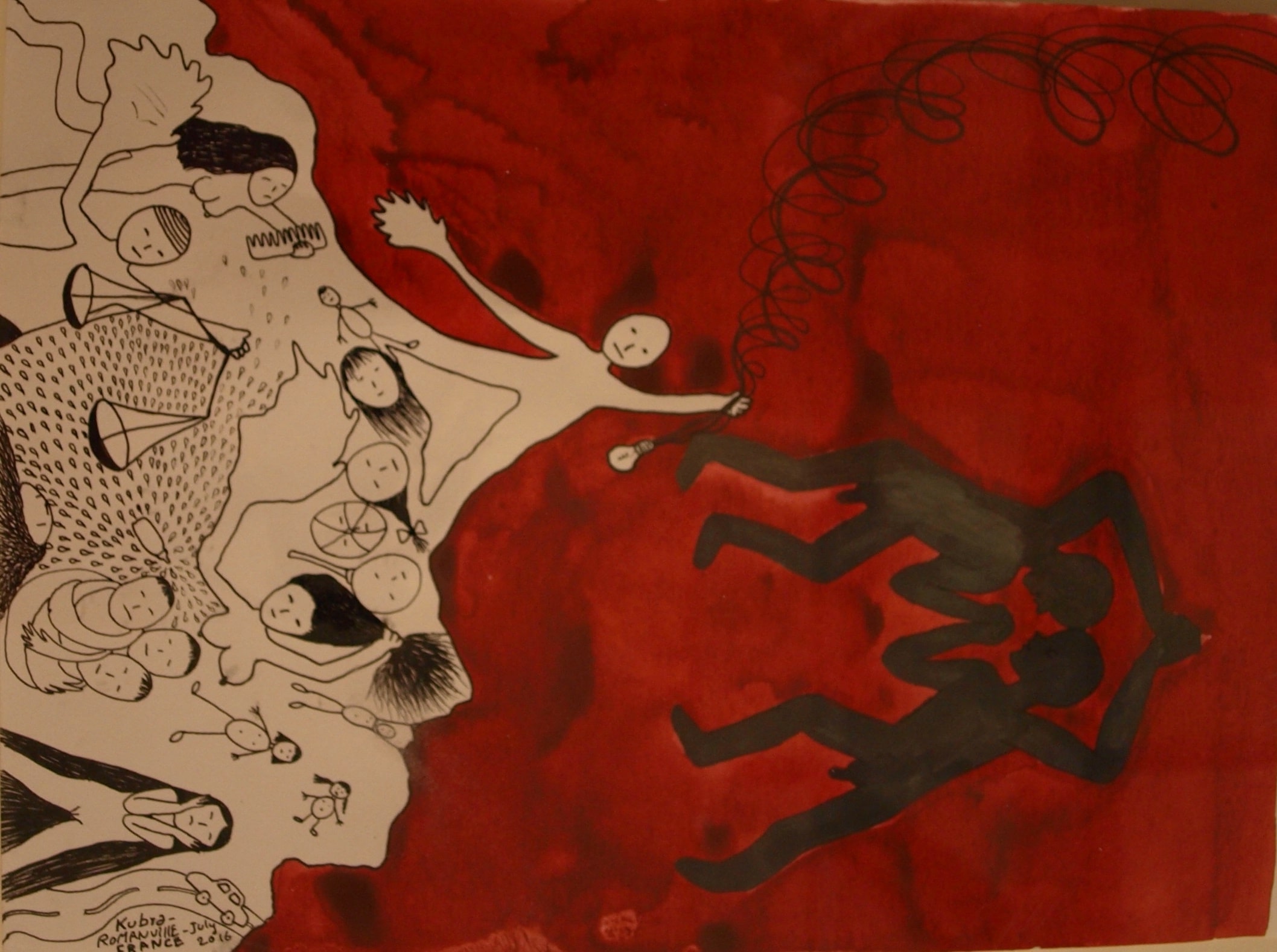

Paris-based Afghan artist Kubra Khademi has upended the notion of “Enlightenment”. From her position as a political refugee and feminist, she focuses on markedly patriarchal societies, and how they are related to motifs of mythology, the history of art, and politics.

Kubra Khademi. The Enlightenment, 2016. Screen printing, 30.6 x 21.9 cm. Reference ME2369. Museu de l’Empordà

Artificial light and modernity

In the mediaeval era, the pace of life for people and cities alike depended on natural light. In the 14th century, the first public lights (the first was installed in Hamburg) changed the dynamics of urban life and became a symbol of development.

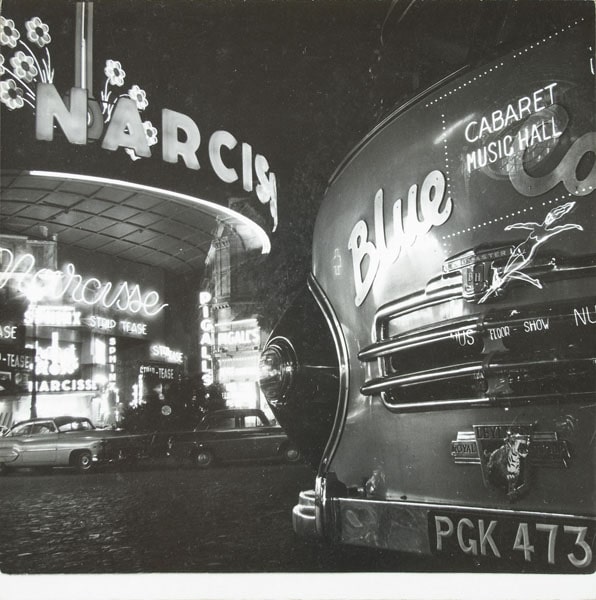

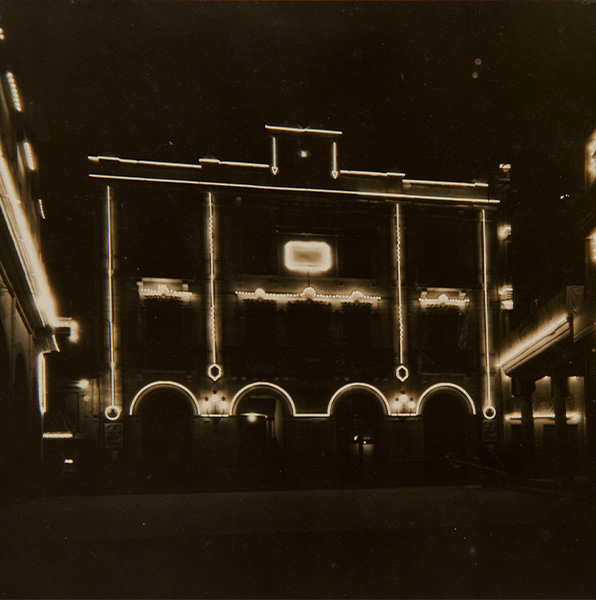

Light in the public space has a representative function, guaranteeing order and surveillance as well as comfort for citizens, while also making it possible to capitalise on the nighttime for transport, industry, free time, and leisure.

Oriol Maspons, untitled, 1955-56. Photograph

Oriol Maspons, untitled, 1955-56. Photograph

Pere Català i Pic, Public lighting. Nice taste, fantasy, enlightenment… Photography, 1931

Palais de l’electricité, 1900. Stereoscopic photograph, 8.4 x 17.4 cm. Ref. MFM S-6661. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero

Alfred Sohn-Rethel. Detail of a Paris theatre, 1904. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquisition for the “5th International Exposition of Fine Arts and Artistic Industries” of Barcelona, 1907. © The author or their heirs.

Henri Meunier. [Automobiles Gobron], 1902. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquisition from the Plandiura collection, 1903. Public domain

Exploring the mechanisms

Photography and cinema are also the consequence of this technological innovation. It is worth taking a moment to look at some of the earliest cameras found in the collections of the Museu Marès.

Workshop camera. Second half of the 19th century. 129 x 165 x 60 cm. Ref. MFM S-6297. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero.

Ernemann Globus. Field camera. First quarter of the 20th century. 136 x 21.5 x 37.5 cm. Ref. MFM S-6441. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero.

Klapp stereoscopic camera. 1896- 1921. Ref. MFM S-6355. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero.

Magic lantern. Second half of the 19th century. Ref. MFM 20991. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero.

Magic lantern slide. Late 19th century. Ref. MFM S-27429. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photo: Pep Herrero.

We should also have a look at some of the more contemporary explorations using these mechanisms.

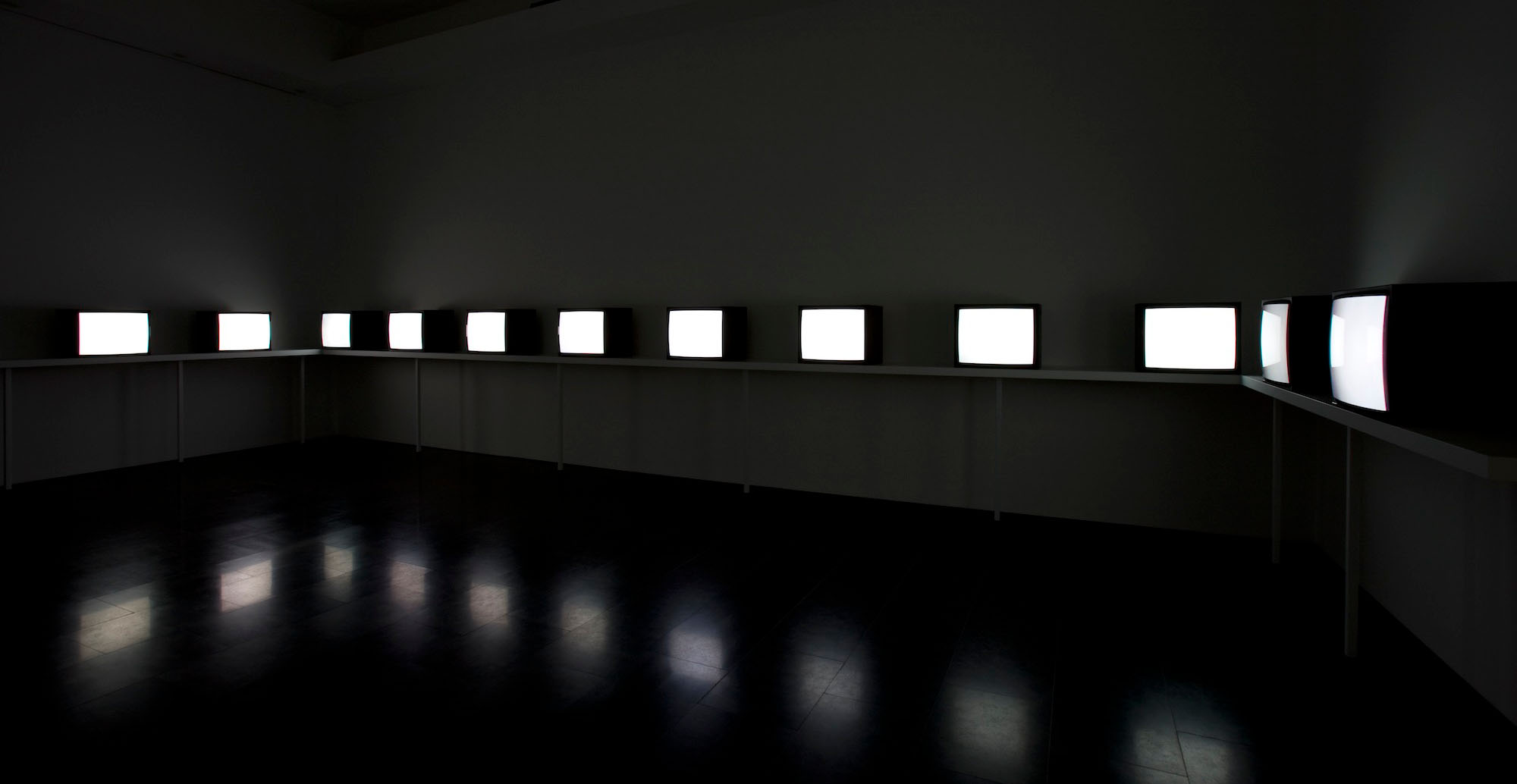

Artists and scientists alike share an innate curiosity and the analytical capacity to explore technical and mental mechanisms. In the case of David Lamelas, the monitors are reduced to projecting light, the baseline condition for cinema cameras.

David Lamelas. Situation of Time , 1967. Emission of vibrating light on 17 televisions. Variable dimensions. R 3741, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. © David Lamelas. Photography: Tony Coll

Nocturn 29 by Pere Portabella is a statement of principles about the cinema.

Pere Portabella. Nocturn 29, 1968. 35 mm film, b/n and colour, sound, 77 min. 58 s. By Pere Portabella. Produced by Films 59. R.1894, MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Donation by Pere Portabella. © Pere Portabella. © Pere Portabella

João Maria Gusmão & Pedro Paiva. Eye model, 2006. Darkroom system with wooden table, ostrich eggs, lenses, and spotlight. Variable dimensions. R.5093, MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Work acquired thanks to the Fundació Puig. © João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva. Photography: Rafael Vargas

Anthony McCall. Line describing a cone, 1973. 16 mm film, b/w, no sound, 31 min. and smoke, variable dimensions. R.2488, MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. © Anthony McCall. Photography: Hank Graber.

Dan Graham. Binocular zoom, 1969. Synchronised adjacent screening of two super 8 films transferred to 16 mm, colour, no sound, 1 min. 7 s. R.2976, MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. © Binocular Zoom by Dan Graham. All rights reserved. Photography: Marian Goodman Gallery.

Barcelona international exposition (1929)

Alicia de Larrocha (originally played by the artist at the age of 6, on 12 December 1929 in the Palau de les Missions in the Barcelona International Exposition).

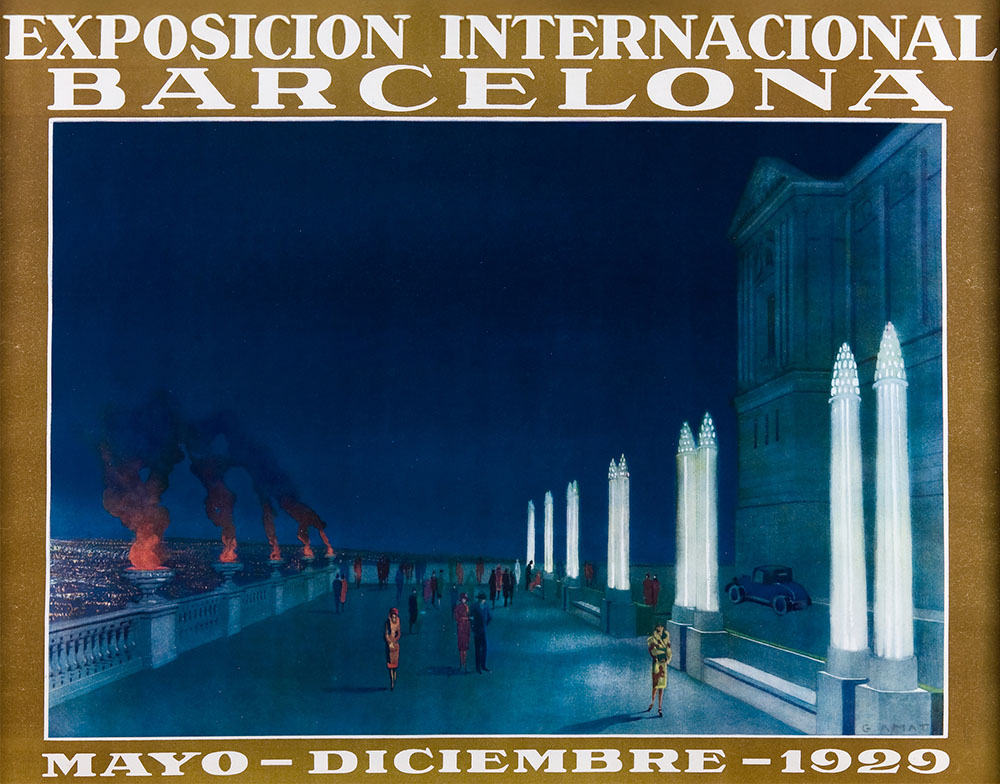

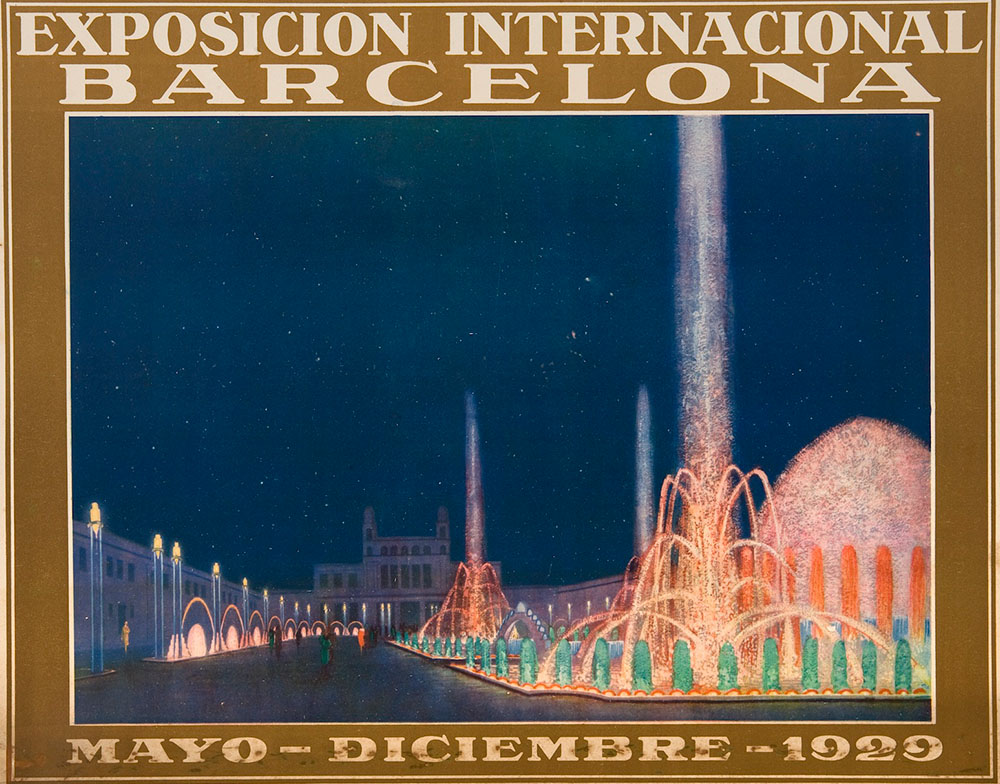

We are now returning to the issue of cities, and there is one case that we cannot overlook: the Barcelona International Exposition (1929). We should recall that shortly before the outbreak of World War I, a decision was made to organise an exposition called the “International Electrical Industries Exposition”. World War I had left the participating countries in a dire situation. Together with the drastic political changes that Spain experienced, this postponed the event until 1929. Since electricity was no longer a novelty, it became known as the “Barcelona International Exposition”. However, light was one of the central themes of the urban planning and ideological project at the heart of the exhibition, based on three elements: the rays of light at the Palau Nacional, the Magic Fountain (designed by Carles Buïgas), and the Columns of Light flanking Avinguda Maria Cristina.

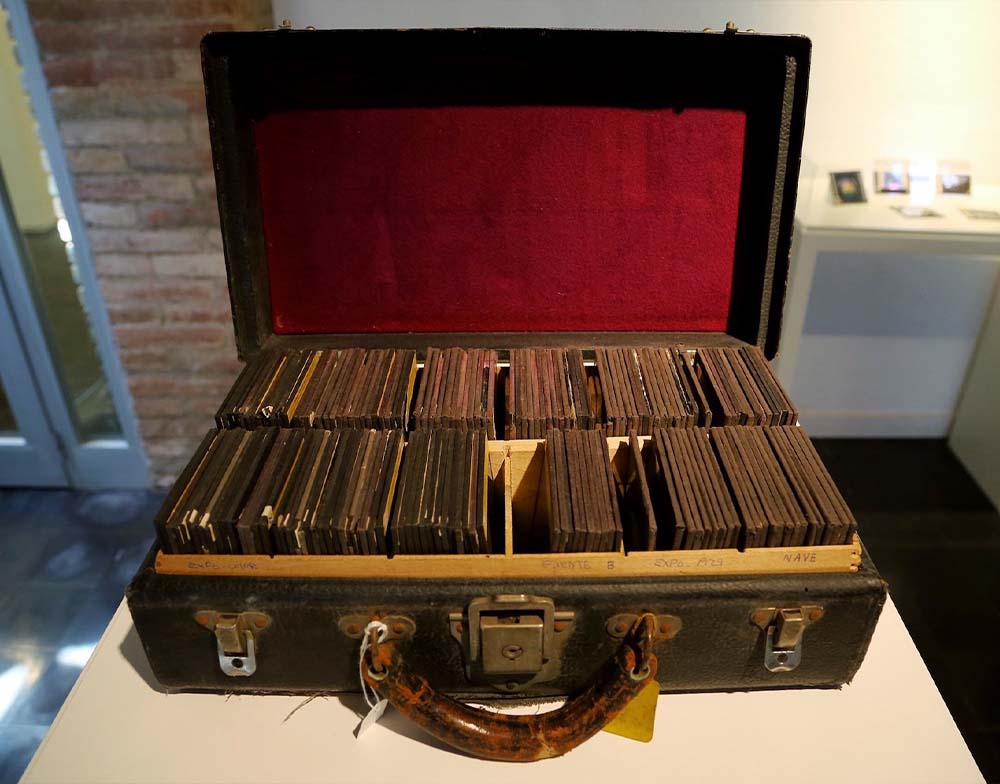

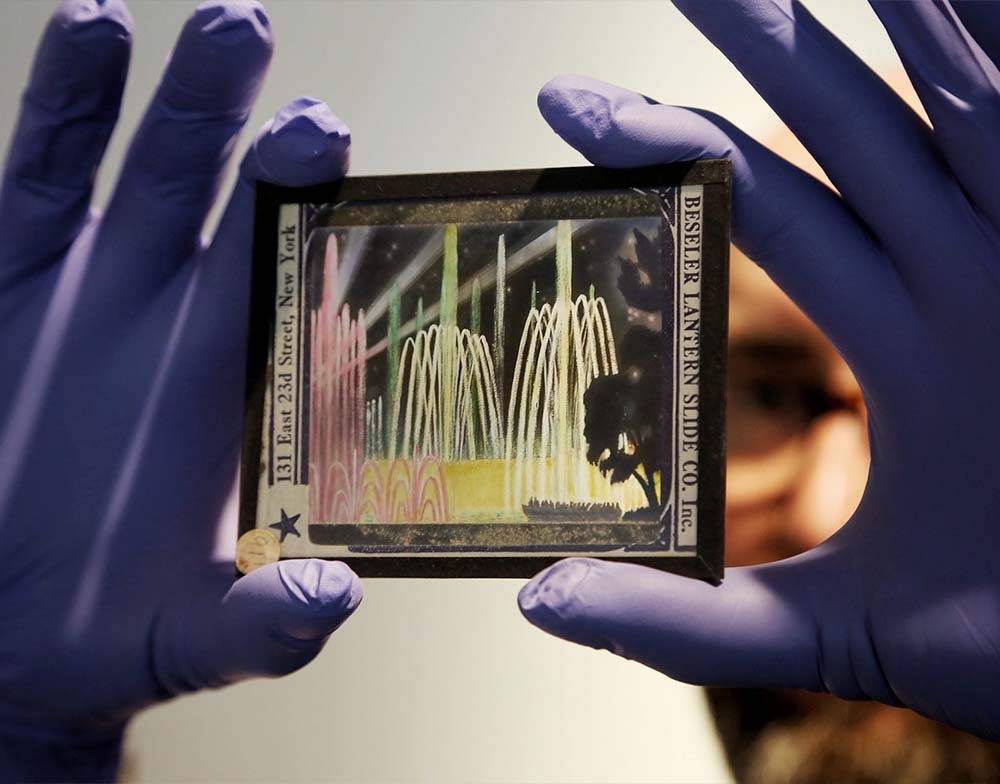

The Museu de Cerdanyola preserves certain elements such as posters, along with Carles Buïgas’s seal and suitcase, full of slides with different views of the project, which form a type of catalogue that he probably used to showcase his projects in order to win new commissions.

Posters of the International Exposition. Barcelona, 1929. Phototype and chromolithography. Impremta Rieusset S.A. Illustrations by Santacreu and Gabriel Amat. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Posters of the International Exposition. Barcelona, 1929. Phototype and chromolithography. Impremta Rieusset S.A. Illustrations by Santacreu and Gabriel Amat. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Posters of the International Exposition. Barcelona, 1929. Phototype and chromolithography. Impremta Rieusset S.A. Illustrations by Santacreu and Gabriel Amat. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Carles Buïgas’s suitcase and a detail of the slides. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Carles Buïgas’s suitcase and a detail of the slides. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Carles Buïgas’s suitcase and a detail of the slides. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Carles Buïgas’s suitcase and a detail of the slides. Donation by Rotary Club Cerdanyola. Museu de Cerdanyola.

Artificial light, progress, technology

Artificial light continues to define the identity and character of today’s cities and, with it, an important part of the public sphere.

Adam Strzelczyk. Koeln at night. Photograph. Registry No.: 6132. Centre de la Imatge Mas Iglesias Reus / Premis Ciutat de Reus de Fotografia - Ajuntament de Reus.

Armand Domènech. Poster for Semana de la Luz. Barcelona, 1966. GAGB 8958/14. Museu del Disseny-Dhub. Photograph: La Fotográfica.

Artificial light is associated with modernity and a future located somewhere between retro chic and sophistication, as we see in certain photographs typical of the 1980s.

Josep Manuel Ferrater. Neon light, Barcelona, 1984. Photograph. MTIB 4117/13, Museu del Disseny-DHub. Photography: Josep Manuel Ferrater.

Pep Àvila. Future Land, Barcelona, 2018. MDB 4053, Museu del Disseny-DHub. Photograph: Pep Àvila.

Light and the public sphere

In the 1950s and 60s, technological development generated more light and more power.

Carles Fontserè Carrió. Back Cover Panel C: Night view of Manhattan skyscrapers, 1955-1968. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Donated by the artist, 1997. The author or his heirs.

The 1970s oil crisis was accompanied by increased awareness about sustainability issues in the use of power and resources. This environmental awareness remains with us today as a matter of great urgency.

Adrian Melis. Moments that Marked the World III. The East is Red , 2013. Single-channel video, colour, sound, 3 min. 36 s. R.5075, MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. © Adrian Melis

Development requires the implementation of new lighting technologies. Lighting can change settings and perceptions and is a key element in sporting and artistic events, as well as national and political celebrations.

As part of the liquid modernity defined by Zygmunt Bauman, the intangible nature of light defines identities and urban dynamics, while giving rise to virtual and illuminated cities, such as Hong Kong, New York, and Las Vegas.

Judith Barry. A l’ombra de la ciutat… vamp r y, 1985. Projection of slides and video on a two-sided screen, colour, sound, continual projection. Variable dimensions. R.3640, MACBA Collection © Judith Barry

Technological development, relentless consumerism, and environmental awareness and sustainability continue to go hand in hand. The oil crisis in the 1970s still impacts us today, accompanied first by greater awareness and by an urgent need to address topics of sustainability regarding the use of energy and resources.

Allan Sekula reminds us of this with his work.

Allan Sekula. Radiation Hazard. Series: “Methane for All” , 2008. Chromogenic photography, 41 x 60 cm. R.4079, MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Repsol Foundation Collection. © The Estate of Allan Sekula. Photography: Christopher Grimes Gallery.

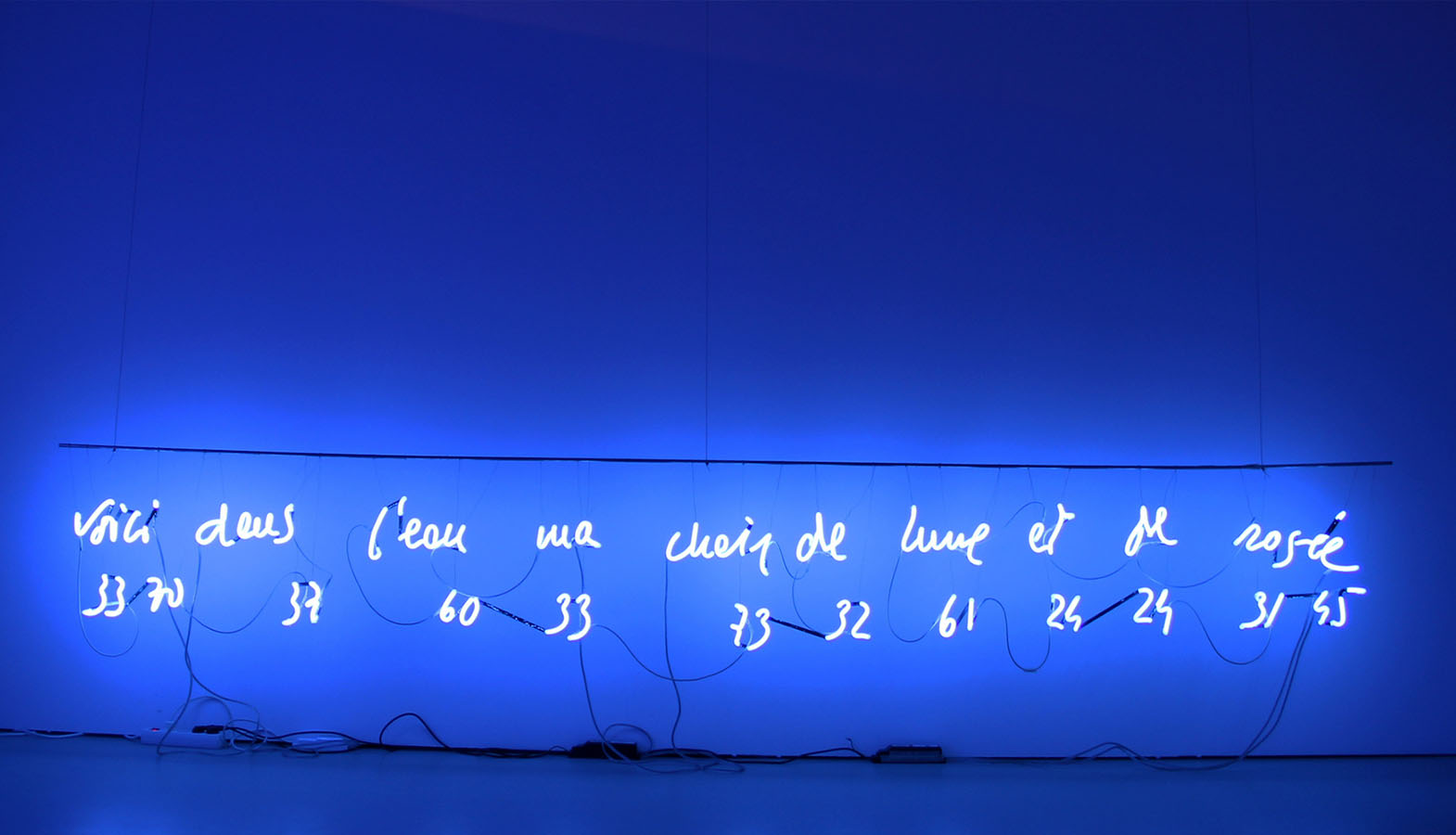

Even back in the 1970s, people highlighted that the notion of sustainable growth is an oxymoron. With his neons that reproduce mathematical formulas, Jordi Benito strives to rethink the conflictive nature of human beings in the world, while rereading Ideas sobre la complejidad del mundo (‘Ideas on the Complexity of the World’, 1985) by Jorge Wagensberg, which emphasises the uncertainty of the environment.

Jordi Benito. Untitled (Meeting Point), 2008. Installation. Museu de Granollers

The FRAU Collective. Visual Research takes Benito as a starting point in order to delve into the need to achieve greater sustainability.

FRAU. Recerques visuals I jo! Amb tot el meu cos llençat a aquestes canyes , 2023. Installation. Museu de Granollers Ref. 12774

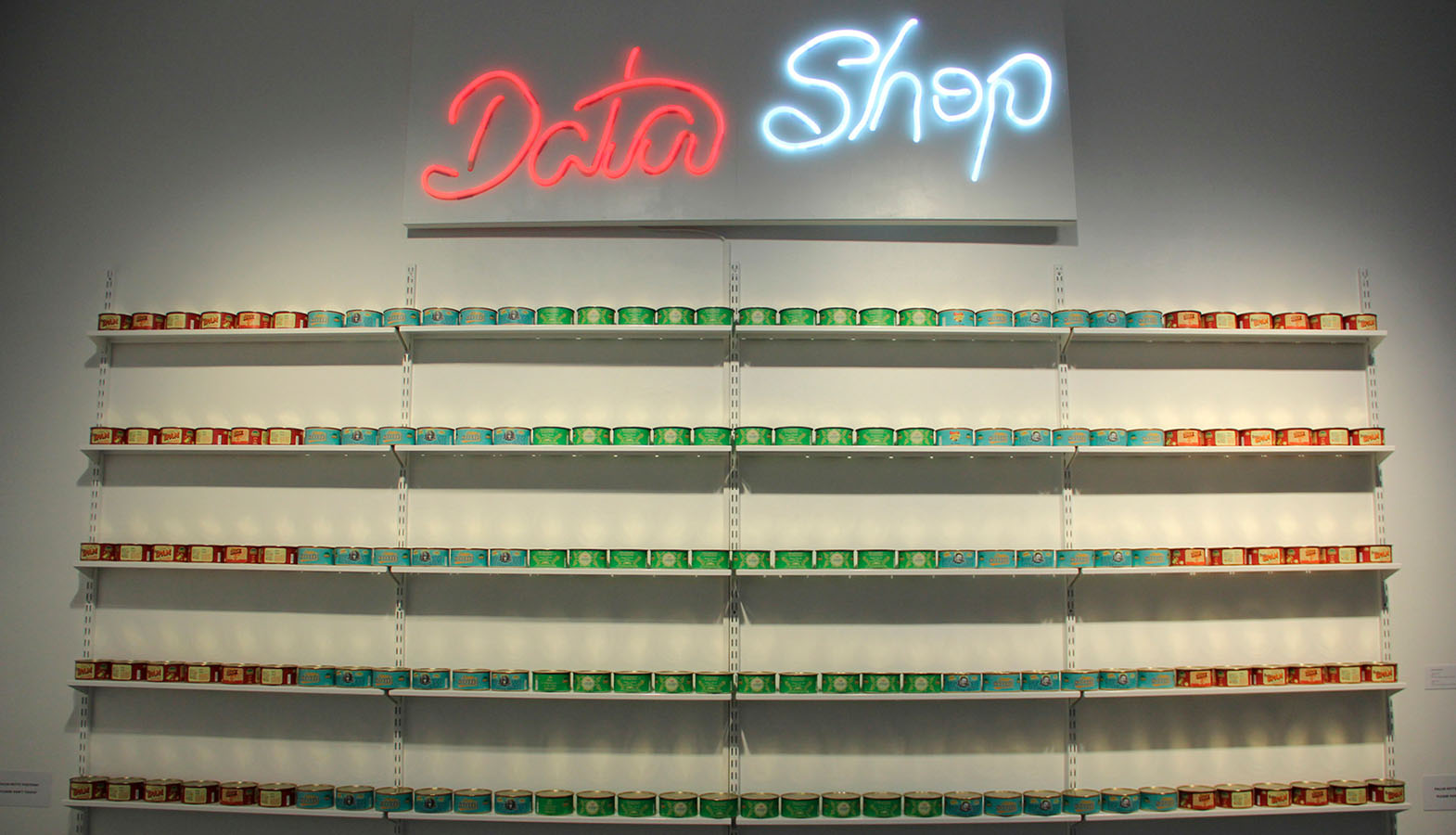

Varvara & Mar also speak about the complexity of today’s world, social changes, and the impact of the technological age.

Varvara & Mar. Data Shop, 2017. installation. Museu Abelló

Although violent conflict has cycled constantly throughout history, war has never been and never will be the answer.

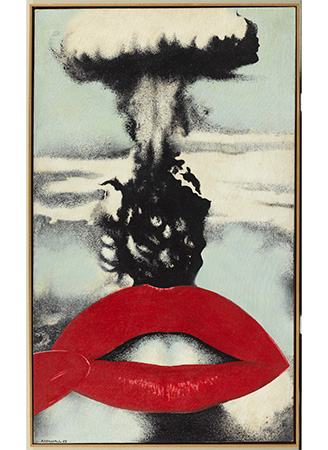

Joan Rabascall. Atomic kiss, 1968. Acrylic on canvas, 162 x 97 cm. R.3219. MACBA Collection. Long-term loan by the Ajuntament de Barcelona. © Joan Rabascall, VEGAP, Barcelona. Photography: Gasull

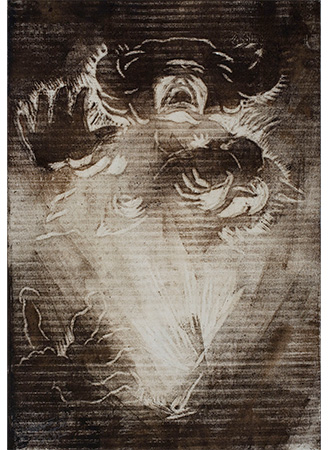

Vicente Gil Franco. Bombardment (obverse) / Sketch of a dog (reverse), 1937. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, coming from the “International Exposition” of Paris, 1937. © The author or their heirs.

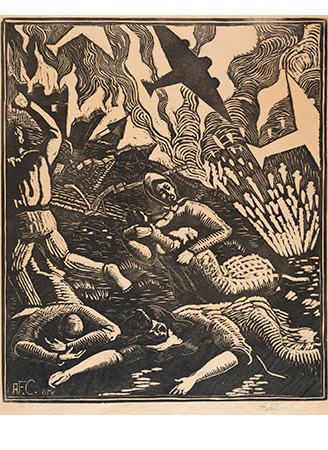

Andrés Fernández Cuervo Sierra. Bombardment, 1937. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, coming from the “International Exposition” of Paris, 1937. © The author or their heirs.

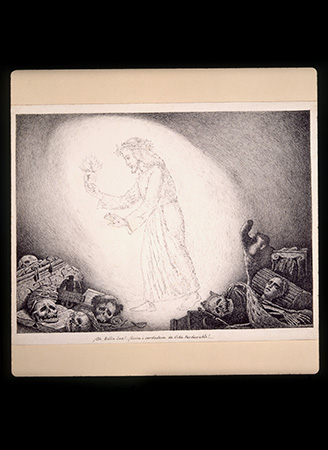

Josep Sancho Piqué. Horrors of a war: ‘Oh beautiful light! … The one and true of everlasting Life!’, 1939. Ink drawing on white paper. 24.5 x 32 cm. Reference: MAMT NIG 1009. Diputació de Tarragona. Museu d’Art Modern. Arxiu Fotogràfic / Alberich Fotògrafs.

Kristin Oppenheimer focuses on this topic as well, with a stripped down version of Hey Joe by Jimi Hendrix, an iconic war protest song.

Kristin Oppenheim. Hey Joe, 1996. Spotlight, speakers, IT system, and sound recording, 2 min. 15 s. Variable dimensions. R.4281, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. © Kristin Oppenheim.

The drawings by Carme Sanglas are a cry to draw attention to our disconnection from the natural environment.

Carme Sanglas. Untitled/Girl shaking out a sheet, 2009. Ink on paper, 21 x 29.6 cm. R. ME 2563. Museu de l’Empordà. © Carme Sangla

Fina Miralles also reminds us of the need to return to the essential.

Fina Miralles. Relationships. The Body’s Relationship with Natural Elements in Everyday Actions. Looking at the Sun, , 1975/2020. Inkjet printing on paper. MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Donation by the artist. © Fina Miralles

She did it in the same way as Joan Miró had done it before her.

Joan Miró. Woman in Front of the Sun, 1974. Acrylic on canvas, 258.5 x 194 cm. R. FJM 4790. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2024.

Without the sun, life would be impossible. It is an essential element, not only for life but also for our future sustainability.

Pedro Torres. House of the Sun, 2020. Various materials. Variable dimensions. R.6293, MACBA Collection. Long-term loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya. National Contemporary Art Collection. © Pedro Torres

To end our journey, we have some “simple” light bulbs that have the ability to remind us of life’s important moments…

Along with social and collective moments.

Iván Argote. Who Didn’t Ever Play to Ancestors, to Prehistory of His Flesh and Blood?, 2013. Light installation, 178 light bulbs, 10,000 cm electric cable. R.5201, MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Private long-term loan. © Iván Argote. Photo: ADN Galeria.