Curator: Maria Garganté Llanes

Number of works: 55

Museums represented: MACBA, MNAC, Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola, Museu Víctor Balaguer, Museus de Sitges, Museu d’Art de Girona, Museu del Disseny, Fundació Palau, Museu de l’Empordà, Museu de la Garrotxa, Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona, Museu de Reus, Museu de Valls, Museu Frederic Marès, MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida, Museu Diocesà i Comarcal de Solsona, Museu Apel·les Fenosa, Museu d’Art de Sabadell, Museu Abelló, Museu de Lleida, MEV Museu d’Art Medieval, Museu de Manresa.

Introduction

The objective of this exhibition is to undertake an exercise in “looking” from our post-pandemic present, based on works from a pre-pandemic past. To see how an image as iconic and integrated into our imagination, such as a Last Supper at a Gothic table, for a year and a half became an unimaginable type of meeting or at least one that was frowned on for health and social reasons. Thus, the exhibition will not be based on a mere collection of works of art about parties, social life in bars or dining, but on the fact that all these activities were eliminated from our lives for a quite a long period in our recent history.

Therefore, we begin with the “shock” of being deprived of this type of interaction and also the difficulty of “relating” again. Does the anxiety to make up for lost time coexist with a certain bitter awareness that something has been broken forever? These are some of the questions that underly our look at art through the works we have chosen.

Thinkers such as Georges Bataille or Émile Durkheim defined an eminently social expression like the party as an institution that challenges the anthropological model of homo economicus, given that it pursues only individual interest, whereas a certain a social solidarity derives from every collective celebration. Thus, homo festus (the collective expression of homo ludens) would also be homo socialis.

Ultimately, human interaction always determines the construction of a social reality. That is why our main objective will be for the exhibition itinerary to evoke what the pandemic deprived us of for almost two years and, at the same time, to symbolise the “recovery”, this time without restrictions.

Festive celebrations of a religious nature:

from Corpus Christi to the Festa Major.

Religious festivals have traditionally had a public dimension, expressed in aspects such as processions that, in the case of Corpus Christi or Holy Week , become the central event. The procession had to be a reflection of the maintenance of social order, so it was about involving all the locality’s important social agents in order to create their best “showcase”.

The configuration of these urban retinues corresponds to a model of celebration that regulates and structures the festival: the space is defined by an itinerary along which the festive characters move. It is worth noting that the Church increasingly distanced itself from the presence of the festive entourage in religious processions, so that in the 19th century a separation occurred. This means that today, elements such as giants or mythical bestiary are associated with a more secular concept of Festa Major (patron saint’s day festival). Nevertheless, the most recent recovery of historic festive processions reintegrates them into their original function.

Felip Masó i de Falp. The Procession of Saint Bartholemew, 1884. Oil on canvas, 115 x 218 cm. Museu de Maricel (Sitges), Cau Ferrat Collection.

Lola Anglada. The Moixiganga of Sitges, 1970. Panel of 25 polychrome ceramic tiles, 62 x 68 x 3.5 cm. Museus de Sitges (Vila de Sitges Art Collection).

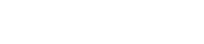

Ester Ferrando: Virgin of Mercy Festival, 2007. Poster. Digital print on paper, 36 x 30.5 cm. MAMT, Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona.

Modest Urgell i Inglada: Dance of the Giants at Night, last quarter of the 19th century-early 20th Oil on canvas. Museu de la Garrotxa.

Giovanni Antonio Canal (Canaletto), Return of “Il Bucintoro” on Ascension Day, 1745-1750. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2004. © Picture: Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

Oleguer Junyent, Corpus (Girona), 1927. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Purchased at the Barcelona International Exhibition, 1929; entered the collection 1931. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023; © The author or his heirs.

The Joy of Sharing a Table

One of the aspects most affected by the pandemic was the collective meals or get-togethers that involved gathering round a table to share a meal. Such social gatherings had to be reduced to the so-called “bubbles”, which were limited to your closest family or the people with whom you had the closest contact. They could not contain more than six people, except for festive Christmas meals, when ten diners were allowed, although from a maximum of two family bubbles. This led to the cancellation of many Christmas lunches and dinners and consequently there were no passionate family discussions or meals with friends and colleagues for the major holidays. From time to time in the media we read of an occasional transgression of the rules by a clandestine group meal that immediately resulted into a rise in contagion or an increase in admissions to the intensive care wards. Restaurants were closed: initially throughout the day and then at night, when sharing a table normally lasts until the wee hours and we already know the dangers that night-time has always brought in the imaginary of law and order.

Joan Abelló: Friends at Dinner, 1951. Oil on canvas, 146 x 200 cm. Museu Abelló.

Pere Teixidor (attributed): Holy Supper, c. 1450. Painting on board. Museu Diocesà i Comarcal de Solsona.

Miralda, Holy Food, 1984-1989. Diverse materials. Variable sizes. MACBA Collection. On loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya. National Art Collection. © Miralda, VEGAP, Barcelona. Photo: Rafael Vargas.

Xavier Nogués: Tiles for the Pinell de Brai Winery, c. 1920. Painted glazed tile, 53 x 286 cm. Museu de Valls. Donated by Maria Martinell.

Passoles Studio (attributed): The Chocolate Party, 1710. Polychrome ceramic tile panel. Museu del Disseny. Photograph: Guillem Fernández-Huerta.

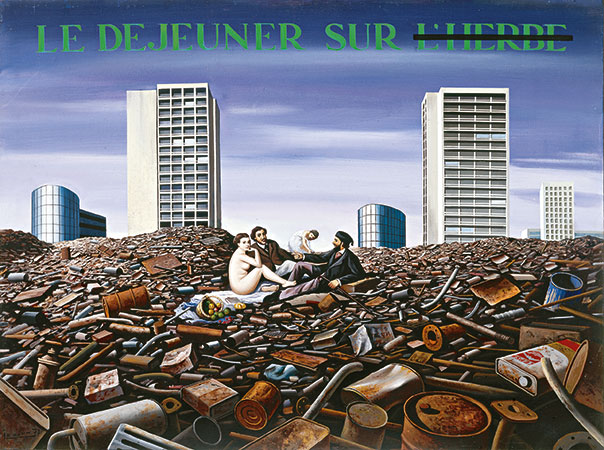

For pleasure. Let’s meet in the open air

When the lockdown measures began to be relaxed, coinciding with the arrival of summer, outdoor gatherings became the most sought-after expression of freedom. In some towns, the opening of swimming pools was postponed and access to beaches was restricted to avoid overcrowding. Social distancing and control measures were imposed and drones were used to ensure they were respected. Young people in particular began to seek alternative spaces to escape this strict control that they perceived as arbitrary. They began to discover waterfalls, streams and ponds where they could meet and cool off. There was a kind of “rediscovery” of the surroundings for recreational purposes, from picnics to nocturnal botellones (outdoor drinking parties), with a single goal: a feeling of freedom.

The selected pictures capture the spirit of enjoying the outdoors, along the lines explained by A. De Saint-Éxupery in Letter to a Hostage (1948): “It was a good sun. Its warmth bathed the poplars on the other bank and the plain, all the way to the horizon. We felt increasing happiness, without knowing why. (…) We were totally at peace, immersed, far from the disorder, in a definitive civilisation.”

Josep Pey, Antoni Serra, Joan Carreras, Afternoon Tea in the Countryside, around 1905-1906. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Purchased in 1967. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2023; © Gaspar Salinas Ramon.

Josep de Togores i Llach: Three Nudes, 1924. Oil on canvas, 130 x 98 cm. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola (on loan from the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya).

Lluís Trepat i Padró: Nuns on the Beach, 1965. Oil on canvas, 60 x 91.8 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i contemporani de Lleida collection.

Joan Padern i Faig: Lunch on the Grass, 1977. Oil on canvas, 97.5 x 130 cm. Museu de l’Empordà.

Ángeles Santos Torroella: The Earth, 1929. Oil on canvas, 69 x 83 cm. Museu de l’Empordà.

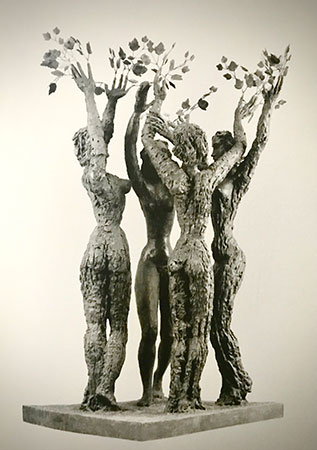

Apel·les Fenosa: Metamorphosis of the Sisters of Phaethon, 1950. Bronze, 235 x 152 x 131 cm. Museu Apel·les Fenosa, el Vendrell.

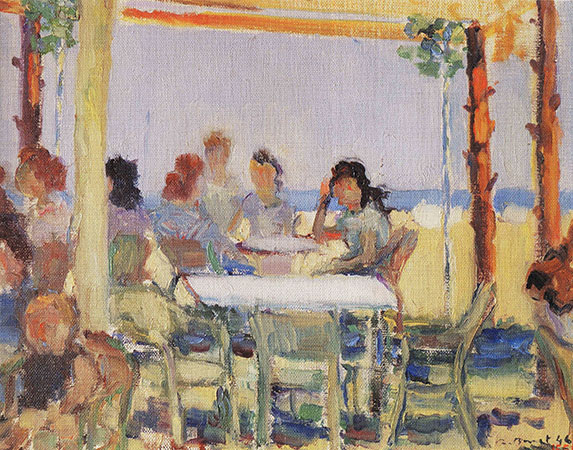

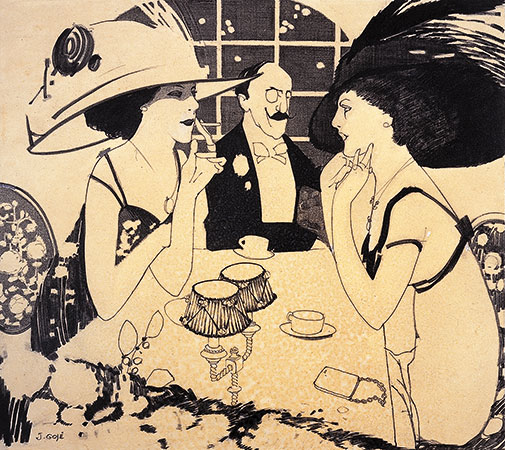

Social leisure. Bars and shows

Bars, the focal point of an important part of social leisure, were among the most missed establishments during the strict lockdown and those on which the focus was placed once the restrictions began to be lifted. Use of the terraces was restricted (no group or table could exceed six people) and night-time opening was not allowed. In short, we experienced the alteration of what some urban planners and sociologists call the “Third Space”, that of socialisation.

On the other hand, “Culture is Safe” was the slogan most repeated by professionals and businesspeople linked to the performing arts. Despite it having been shown that going to the theatre was not a source of contagion –the capacity limitations, social distancing and hygiene measures were scrupulously observed in most cases– it was a sector severely punished by prolonged closures. Why were the scapegoats those spaces where people tend to be happy?

Jaume Pons Martí: The Cafè de la Vila in the Plaça del Vi, Girona, 1877. Museu d’Art de Girona. Girona Provincial Government Collection. Photo: R. Bosch.

Josep Llovera Bufill, Flamenco Dance, 1892-1896. Painting on canvas, 104 x 159 cm, Museu de Reus (on loan from the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya).

Rafael Benet: The Terrace or the Shade, 1946. Oil on canvas, 27 x 35 cm. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer.

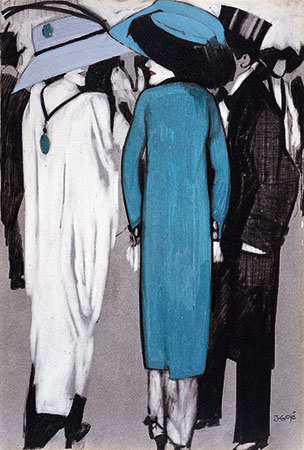

Xavier Gosé i Rovira: In Montmartre, c. 1908. Graphite pencil and ink on cardboard, 32 x 35 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection.

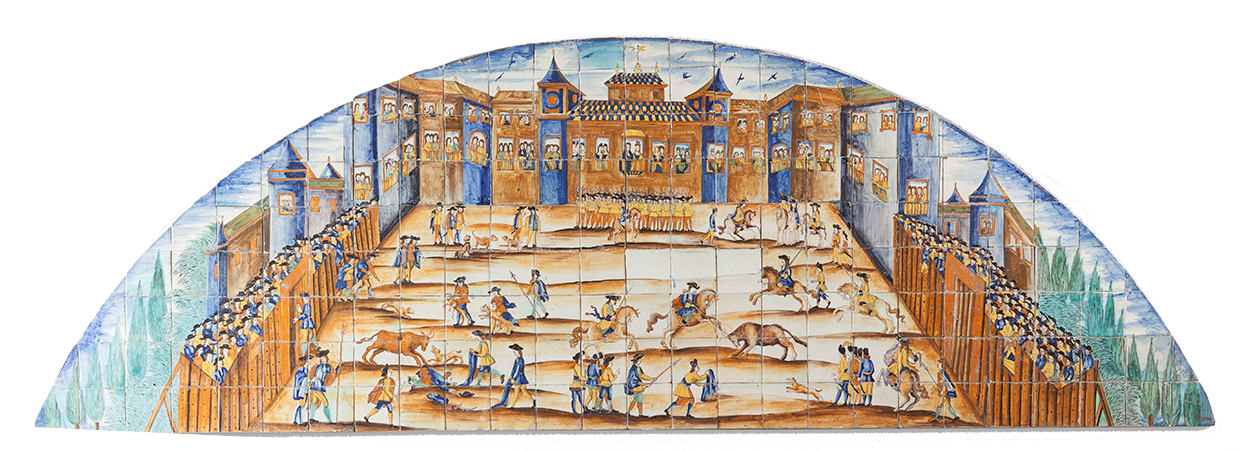

Passoles Studio (attributed): The Bullfight, 1710. Polychrome ceramic tile panel. Museu del Disseny. Photograph: Guillem Fernández-Huerta.

Public Privacy. Rites of Society

Among the social rituals most affected by the pandemic were weddings, which are still one of the quintessential family events that involve showing off in society, not only to the extended family, but also to friends. The wedding, moreover, consists of different parts, all of which were prohibited during the strictest moments of lockdown: the ceremony (civil or religious), the banquet and the dance. Some media spoke of the “emotional loss” for the couples forced to postpone what advertising still wishes to define as “one of the happiest days” of their lives.

Other social rituals par excellence that were truncated include the celebration of births and funeral ceremonies. With the former, newborns could not be visited to share the joyous moment. In the case of the latter, the pain of a solitary death in a hospital or care home was compounded by the impossibility of family and friends to come together to express their grief.

Olga Sacharoff, A Wedding, around 1921. Donation from a group of friends and collectors, 1968. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023; © The author or her heirs.

Anonymous: Group of the Holy Sepulchre, last third of the 15th Polychromed wood, 168x15x48cm, 174x51x45cm, 170x51x35cm, 171x55x36.5cm, 180x57x39cm, 175x55x34cm. MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval, Vic. © MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval.

Ramon Tusquets, The Burial of Fortuny, 1874. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Purchased in 1904. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Antoni Samarra i Tugues: Religious Festival in Ponts, 1913. Charcoal and pastel on paper, 33 x 22 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection.

Jan Van Roome: The Supplication of Mestra / The Marriage of Mestra, c. 1500. Museu de Lleida.

Joan Grau: Nativity of Jesus and the Adoration of the Shepherds (fragment of the altarpiece of the Rosary from the monastery of Sant Pere Mártir in Manresa), 1642-1646. Polychrome poplar wood. Museu de Manresa.

Antoni Viladomat: Baptism of Saint Francis. Between 1729 and 1733. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, on loan from the Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi, 1902; entered the collection, 1906, public domain.

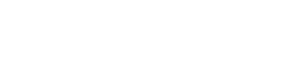

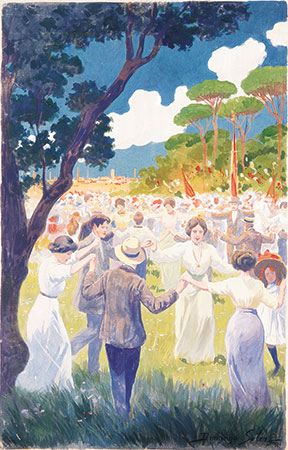

Shall we dance?

The dance can be ritual in the context of a certain tradition. It involves an audience that applauds and endorses it, or it may be merely for fun, without ignoring the fact that a big festa major marquee dance or disco is also ruled by rituality, ranging from exhibition to courtship. The proximity and contact provided by dance was outlawed during the pandemic, when a necessary “social distance” was advocated. Sardanes were allowed if the dancers held a handkerchief or piece of cloth by two ends, so as to avoid hand contact. On the other hand, the festa major dances were suppressed and often reduced to outdoor concerts, which had to be witnessed sitting in well-spaced chairs, while the body was deprived of the expression of movement that follows the rhythm of the music.

Domènec Soler, Lema: For Sabadell, 1911. Gouache and pencil on paper, 112 x 73 cm. Museu d’Art de Sabadell / Sabadell City Council

Francesc Vayreda i Casabó: The Marquee Loge, 1921. Oil on canvas. Museu de la Garrotxa. On loan. Private collection.

Marià Vayreda i Vila: Ball del Gambeto, a Riudaura, 1890. Museu d’Art de Girona. Girona Provincial Government Collection. Photo: R. Bosch.

Ismael Smith: Dancers, 1906. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola. Photo: Jordi Puig

Anonymous: Peasant Scene, 18th Oil on canvas, 53.5 x 85 cm. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer.

Ramon Casas i Carbó: Dance in the Moulin de la Galette, 1890-1891. Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.4 cm. Museus de Sitges.

Taking the street (I). Leisure and business.

The street was forbidden territory during lockdown. We could view it from our balconies. Its casual occupation –whether by children playing or people walking– was banned and unauthorised use was often denounced by one’s own neighbours. It was not a pleasant situation and fluctuated between imponderables such as fear, obedience and the uncertainty of it all. Some measures that regulated access to the public highway were very controversial, such as the permissiveness regarding walking dogs versus the ban on going out with children. Leaving the house to put the rubbish out became one of the most coveted activities in the daily routine and one of the rare moments in which to recall the taste of freedom.

However, the street is not only a place for leisure, but also a place in which to do business. This was affected by the ban on street markets and fairs that lasted for many months.

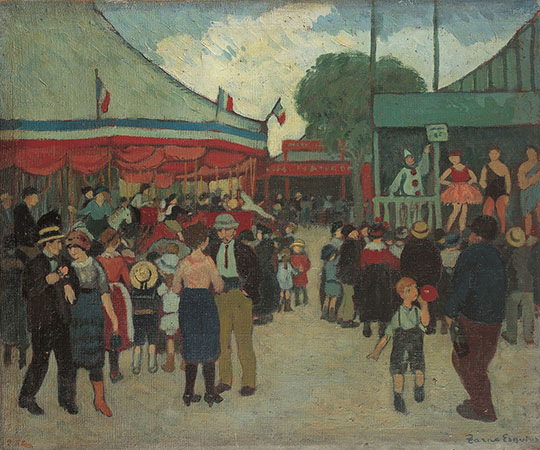

Torné-Esquius: Montmartre Fair, c. 1915. Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 59.2 cm. Fundació Palau, Caldes d’Estrac.

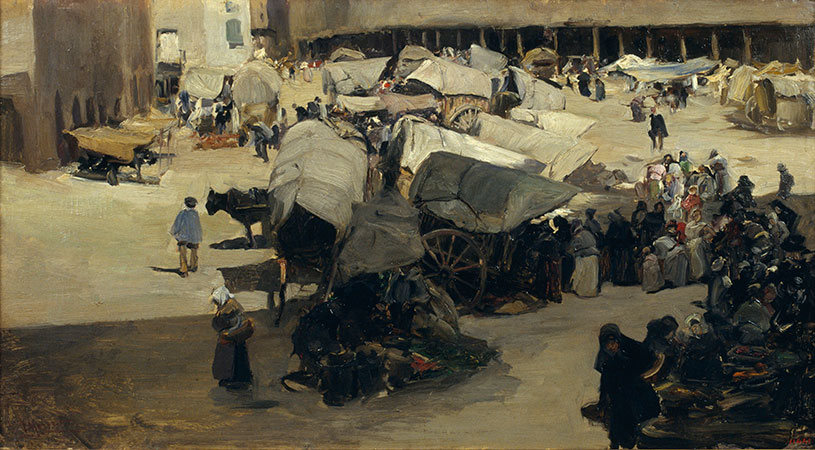

Jaume Morera, Market in Santa Coloma de Queralt, around 1895. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Donated by the artist’s widow, 1928. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Josep Blanquet i Taberner: Climb to the Castle, 1899. Oil on canvas, 70 x 93.5 cm. Museu de l’Empordà.

Josep Bernat Flaugier or Salvador Mayol: El Pla de la Boqueria, 1810-1820. Oil on canvas, 54 x 130.5 cm. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer.

Xavier Gosé i Rovira: Promenoir, c. 1912. Pencil, ink, gouache and fixative on cardboard, 39 x 27.5 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection.

Taking the street (II). The streets will always be ours?

During lockdown we were able to see how health-related fear emptied the streets, not only because it was forbidden to use them idly but because any demonstration or action of mass protest was also unfeasible. Breaking the rules often meant being reprimanded by one’s own neighbours and we began to speak, informally, of the “balcony police”. In this respect, little by little the occupation of the street through the terraces of the hospitality industry was progressively allowed. Even before that, time slots were established for going out for a walk. However, manifestations of a festive and reclamatory nature –retinues, parades, etc.– took the longest to be re-permitted and it was not until 2022 that it was possible to convene them again normally. But what has been the underlying effect of almost two years of paralysation?

Antoni Estruch, Demonstration for the Republic, 1904. Oil on canvas, 141.5 x 201.5 cm. Museu d’Art de Sabadell / Sabadell City Council.

Ramon Casas i Carbó: The Charge, 1899-1902. Oil on canvas. Museu de la Garrotxa (on loan from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía de Madrid).

Josep Berga i Boix: Subjugating Catalonia, 1877. Museu d’Art de Girona. Girona Provincial Government Collection. Photo: R. Bosch.

Joan Abelló: La Diada, last quarter of the 20th Oil on canvas, 89 x 116 cm, 107.5 x 134.5 x 6.5. Museu Abelló.

Anonymous: Santa Úrsula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins, late 15th Tempera on wood, 139 x 46, 5 x 8 cm. Museu de Reus

Other meeting places

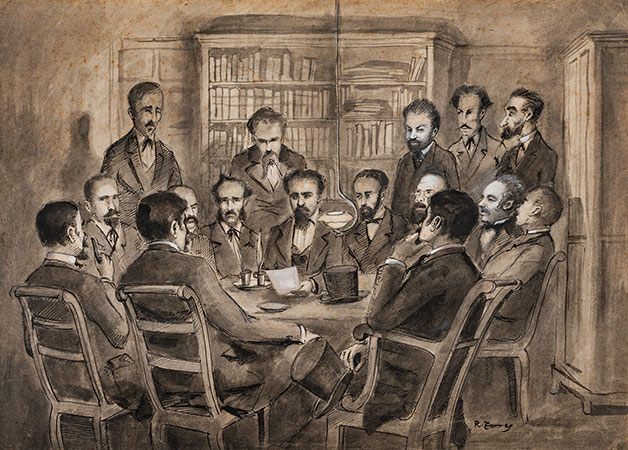

In the harshest moments of lockdown, the only meeting spaces beyond the home were virtual. We connected via Zoom, Meet, Teams, etc., the 21st-century agoras in which we could come together, converse and debate. We also “learned” to work “online” from the solitude of our own homes. In this section we show some meeting places that were forbidden to us: coexistence in a work or teaching environment; the backrooms of shops as gathering spaces; or the laundries of years gone by as places of female confidence and conviviality.

Finally, “visiting” someone during the pandemic also became a utopia and prudence or fear made a big hole in people’s social habits for a long time.

Joan Grau: Jesus among the Doctors of the Law (part of the El Roser altarpiece from the monastery of Sant Pere Màrtir in Manresa), 1642-1646. Polychrome poplar wood. Museu de Manresa.

Ramon Torres Prieto: The Shop Backroom of Pitarra, c. 1945. Drawing on paper, 28.8 x 40 cm. Museu Frederic Marès.

José Gutiérrez Solana, Gathering at the Apothecary’s House, around 1934. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Acquired at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in Barcelona, spring 1942. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya; © José Gutiérrez Solana, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Leandre Cristòfol Peralba: Rinsing (Laundry), 1954. Chestnut wood, 113.2 x 153.8 x 13.3 cm. Donated by Leandre Cristòfol, 1990. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection.

Lluçà Workshop: Altar from Santa Maria in Lluçà (Visitation), 1210-1220. Tempera on wood, 104.5 x 178.5 x 6 cm; 102 x 107.5 x 6.5 cm; 101.5 x 107 x 6.5 cm. MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval, Vic. © MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval.

The Visitation of Mary to her cousin Elizabeth (mother of Saint John the Baptist) is an episode from the New Testament recounted in the Gospel of Luke (1:39-56): At that time Mary readied herself and hurried to a town in the hill country of Judea, where she entered Zechariah’s home and greeted Elizabeth, who in a loud voice exclaimed: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the child you will bear! But why am I so favoured, that the mother of my Lord should come to me?”. On the Lluçà frontal the two women are the absolute protagonists of the scene, while later the figures of Joseph or Zechariah would be incorporated.