Ways of saying I

Curator: Cristina Masanés

35 works

32 artists

9 museums: Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola / Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona / Museu d’Art de Girona / Museu d’Art de Sabadell / MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida / Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona / Museu de l’Empordà / Museu de Manresà / Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

I, or self-concept, is quite modern. Firstly, in the 17th century, it was necessary to formulate it as a concept. Later, in the 18th century, the self-portrait began to be important. Finally, in the 19th century, it became popular among the bourgeoisie to record their private lives in personal diaries. It was modernity that fostered a notion of identity as an introspective process that led the depths of the soul to emerge into a supposed authentic I. Whether it be the I thinking about the essay, the painted portrait or the private voice of those writing a diary, what is in play is the always awkward question of “Who answers to my name?”.

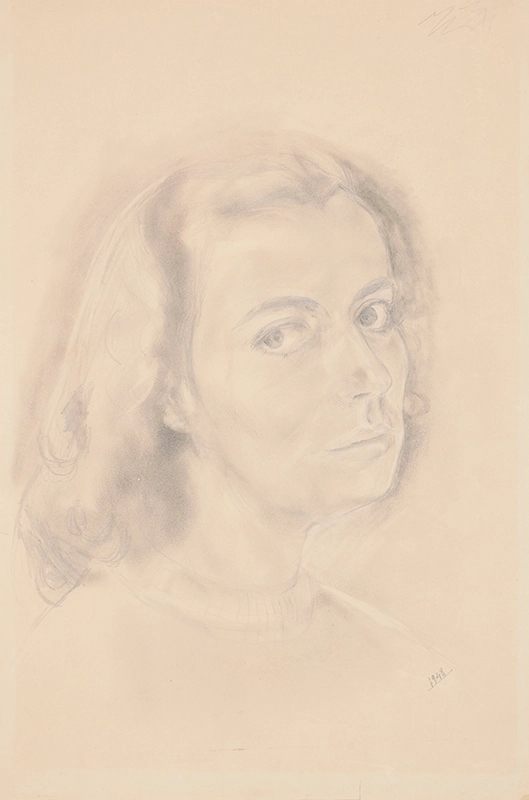

In modern self-portraiture, the artists –men, of course– often present themselves as masterful creators or tortured souls. They depict themselves in their studios, as well as sometimes playing social roles or displaying connections –perhaps with their families– of mastery or patronage. Female artists, although they have been mainly presented as objects and rarely as subjects, cannot be said not to have portrayed themselves. As a proclamatory gesture, much work remains to be done and, perhaps as a result of the interest for their own image or due to a privileged physical awareness, we also have self-portraits signed by women. More than you would imagine at first.

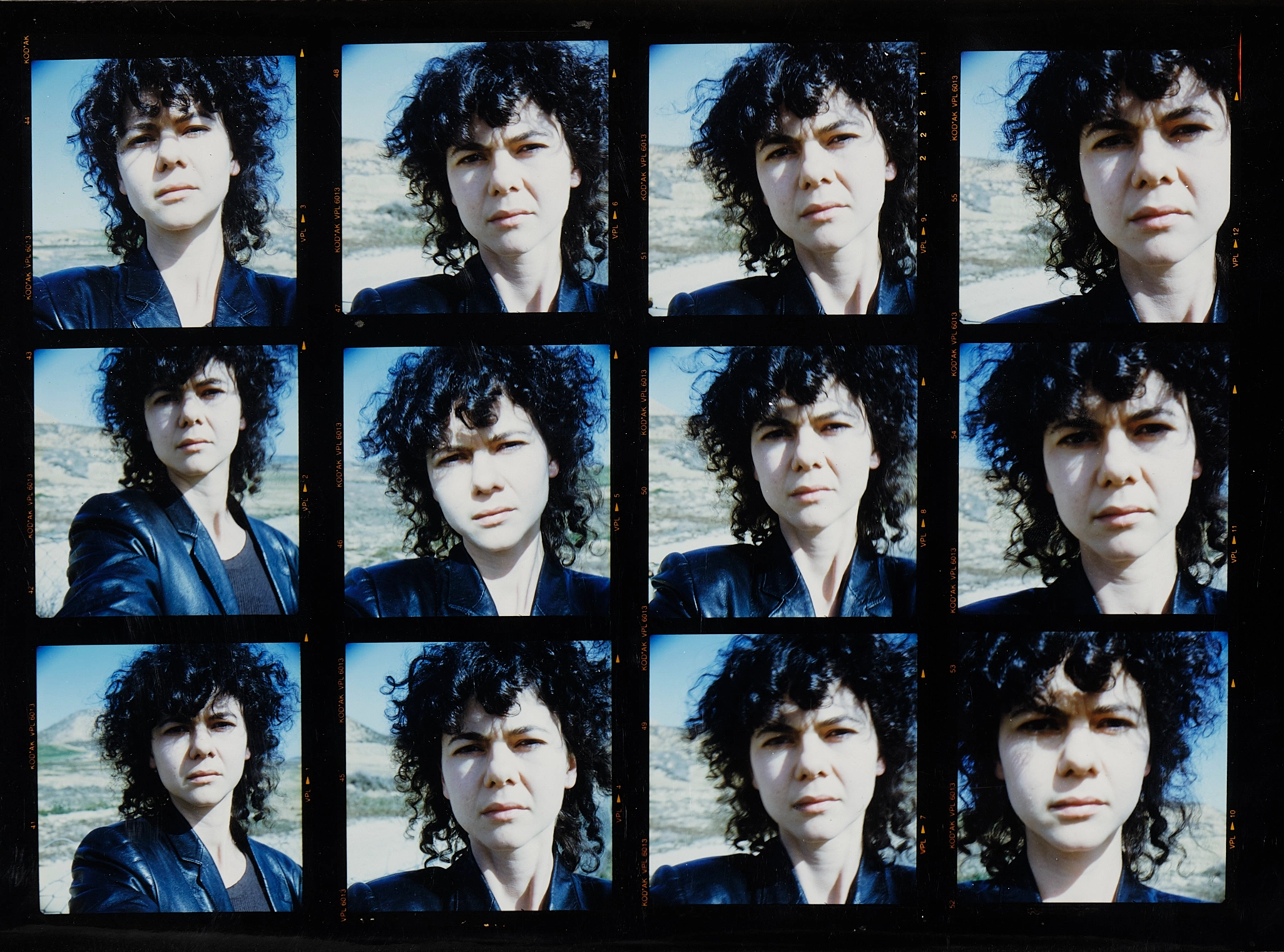

This is a virtual journey through the collections of the Art Museums Network of Catalonia in which we have traced a line between the different self-portraits of women. Very few women artists paint themselves painting. The first canvases –from the late 19th century– incorporate the pictorial canon of the portrait. However, it was from the 1960s that self-representation of women artists became widespread, expanding the very notion of self-portraiture. It is evident that feminism played an important role in this, as well as the idea of a porous subject linked to post-modernity and the freedom associated with contemporary art.

It is not easy to depict yourself, even in the age of the selfie. In addition to technical ability, a certain psychological honesty is required “to be able build up an image in which I recognise myself”. Needless to say, in this process the face takes the largest part of the cake and, naturally, along with the face comes the look. However, that is just the tip of the self-representation iceberg. We invite you to follow some of its driftings, bearing in mind the performative risk of the self-image: “If I show what I’m like, I might end up resembling myself”.

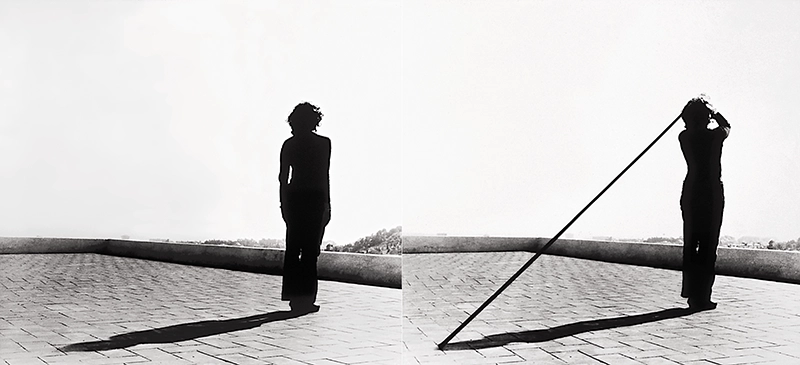

Anatomies: when the I is spoken with the body

There are many portraits that, following the rules of the tradition, concentrate on the face and the look, seeking all that is specific. Sometimes it is the breadth of the cheekbones, the inclination of the head or the intensity of the eyes. Pepita Teixidor, Trini Sotos, Maria Teresa Ripoll, Maria Noguera, Joaquim Casas and Ana Maria Smith chose that option. There are no full figures; at the most, they are three-quarter length portraits. Neither do we have any fragmented bodies until well into the 20th century when, in a clear metonymy, the artists decided to take a part for the whole. Hands, feet, breasts, heart, lungs and other parts of the anatomy are the focus of the works of Ana Sánchez, Ester Fabregat and Laura Cirera. Is the fragmented body of the subject contemporary? Or is it the prehistoric essentiality that is so well invoked by Ana Mendieta with her self-portrait in a leaf? The fact is that, also in art, the I is often expressed with the body.

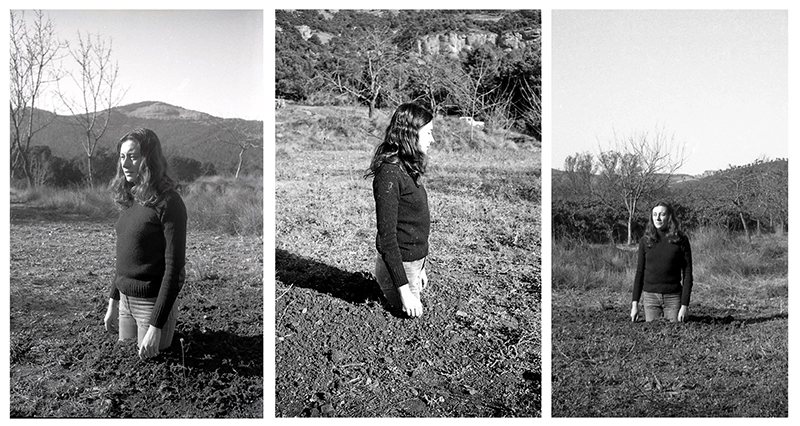

A biographical I

Sometimes the anatomy is not sufficient and a biographical I emerges. An I that cannot be recognised in a moment frozen in time, but is found in the temporality of life. These are the portraits in which a life story is explained and in which the self-image is constructed as a report. It is Fina Miralles’ return or Cristina Núñez’s photographed youth. It is the link with the mother evoked by Ana Marín, Andrea Lerín’s dialogue with her father, Mari Chordà’s uterine maternity, Carme Coma and Montse Gomis’ family album, or the figure of Barbara Stammel’s sister. In all of them there is a subject launched into time and the inexhaustible plot of relationships and bonds.

Reverberations of the I

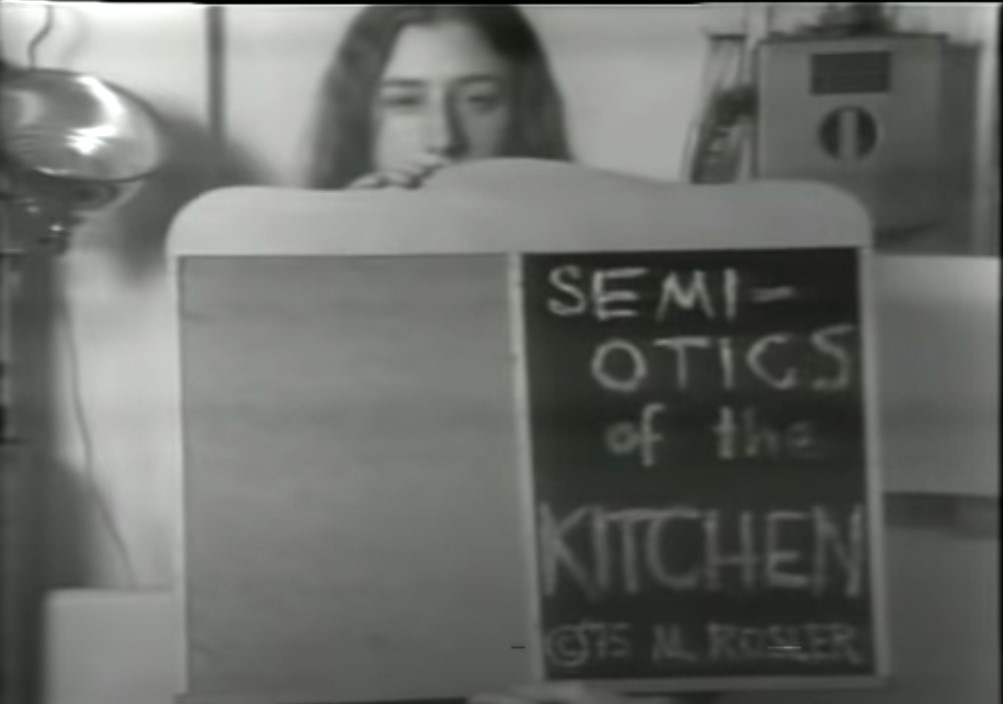

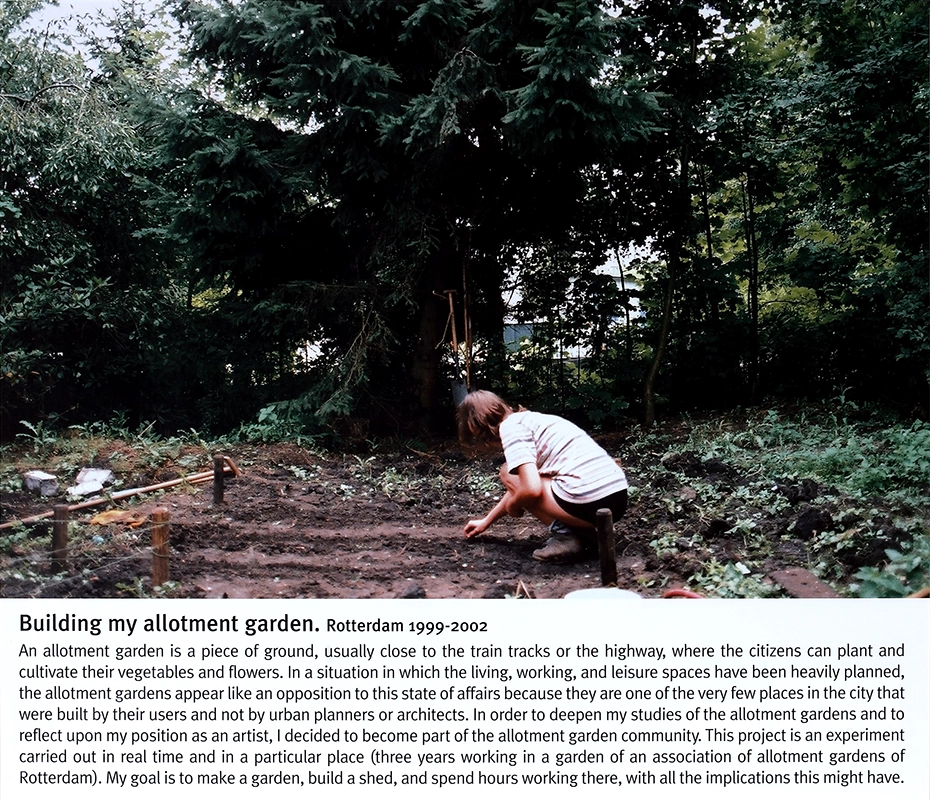

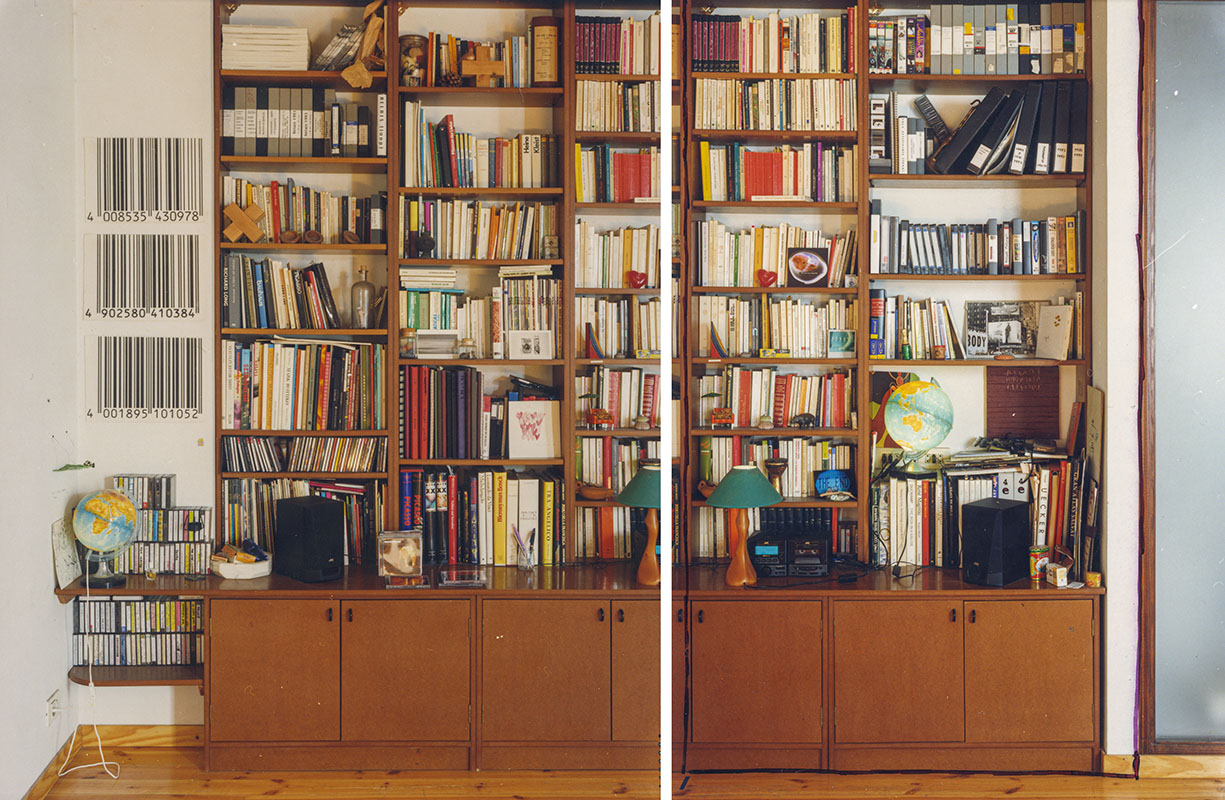

In around 1899, Lluïsa Vidal painted herself in Barcelona wearing her artist’s smock and holding her palette and brush. To tell us who she is, she is explaining what she does. In addition to asserting the right of women to become professional artists, it is interesting to see how the I is often explained by depicting an activity in which one recognises oneself. Other artists have portrayed themselves in their studios, including Núria Batlle, although 101 years separate one studio from the other. In place of the studio, Neus Buira reveals the environment associated with the inner journey and discovery that is the personal library, while Lara Almarcegui shows us her work in the allotment garden as a personal and social growth project. And if we are speaking of extensions or reverberations of the I, we cannot ignore the domestic space, denounced in this case by Martha Rosler and her objectual kitchen.

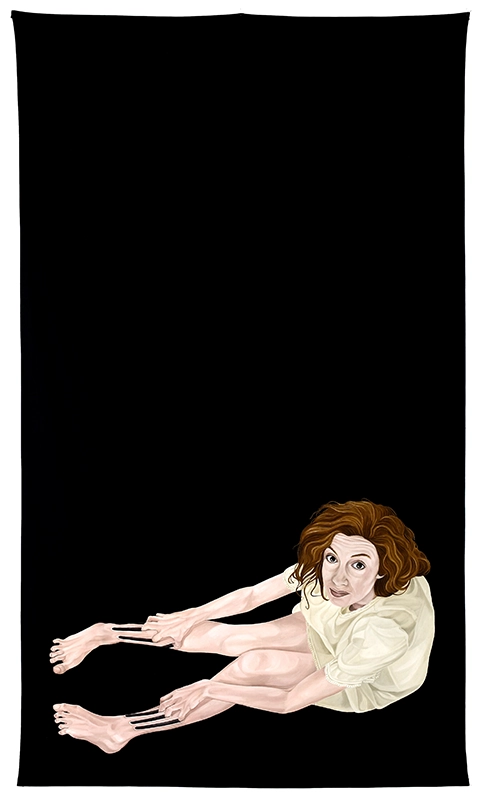

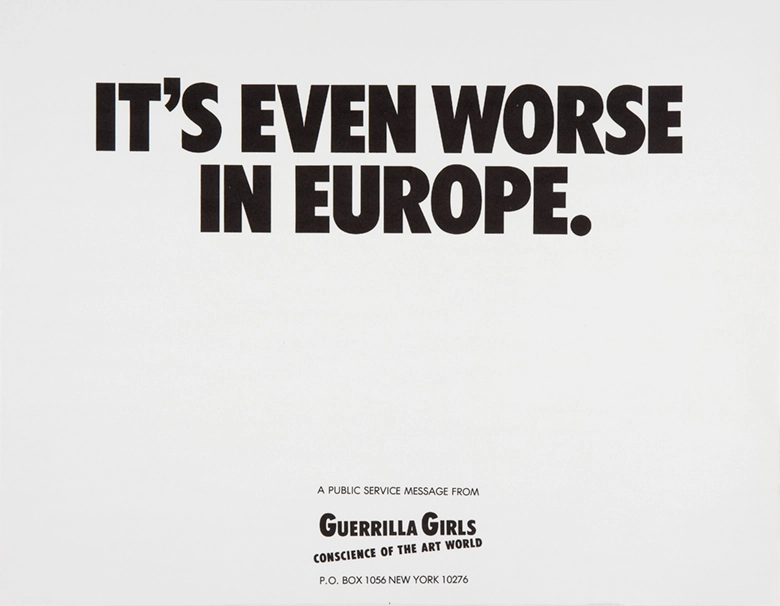

Intentionally political bodies

In creating a self-portrait, there are those who shy away from introspection to understand the body not as a natural organism nor as a self-defining element, but as a political construction or an artefact of social architecture. It is in this paradigm that we find some of the contemporary artistic practices that criticise the very notion of identity. They are the intentionally political bodies of Núria Güell that investigate the I among the citizenry through the idea of the homeland, and those of Jo Spence that revoke the pictorial imaginary of maternity. It is the Guerrilla Girls’ denunciation of the patriarchy in the sphere of art, the demonised otherness of Marina Núñez, and the denied pleasure invoked by Ana Laura Aláez. Finally, and with considerable irony, Esther Ferrer dismantles the myth of nudity as the privileged place of intimacy.

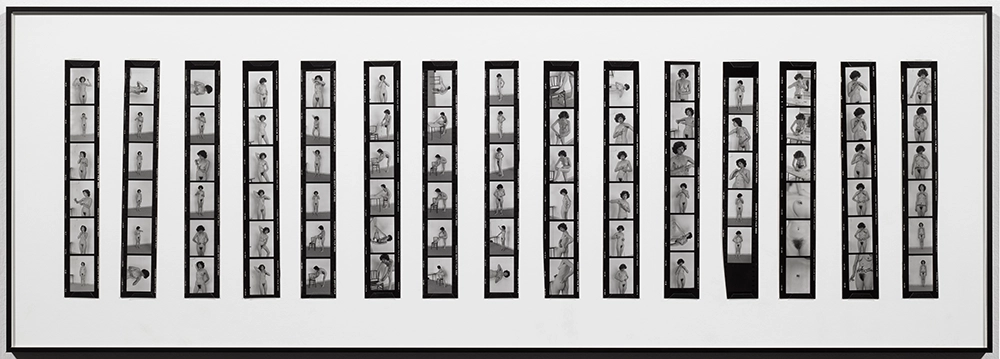

“This action can be carried out by one person on their own or by many people at the same time, without regard for sex, age or condition. It can also be carried out by some people on others, in couples or in a line; the first person is measured by the second, who in turn is measured by the third, etc. They can be naked or clothed, standing or lying down, in any position and situation; in front of a large audience or in the most absolute solitude.”

Esther Ferrer (San Sebastián, 1937) wrote instructions for carrying out this action in 1971. She performed it herself in 1977 and has repeated it several times since. That such intimate and personal elements as the different parts of a naked body can be turned into simple objects to be measured is the politic statement of Ferrer’s action. Reduced to a pure statistic, where is the myth of nudity? Is intimacy no more than quantitative data? Ferrer ends the text with a dose of irony, “If the result has fully satisfied you, begin again as many times as you like.”