Curator: Miquel del Pozo

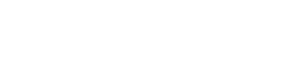

Àngel Jové Jové: Metafísica III, 1976. Varnish emulsion and adhesive velvet on photographic paper, 82.8 x 130.5 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection.

[1] Marcel PROUST (1954), «Le temps retrouvé» A la recherche du temps perdu. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, pp. 256-257

Fina Miralles Nobell: Relationships. The Body’s Relationships with Natural Elements: Water. Look at the sea, March 1975. Photograph. Museu d’Art de Sabadell. © Fina Miralles Nobell

First the artist looks and then we see

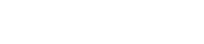

Ramon Casas: Looking for a Subject. Madrid, ca. 1904. Graphite pencil and watercolor on paper, 12.3 x 17 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, acquired from the Plandiura Collection, 1932. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Santiago Rusiñol: Female Figure, 1894. Oil painting on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Legacy of Santiago Espona, 1958. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Three ways of looking: those of today, yesterday and the day before yesterday

Piece of slate with an engraving depicting a young deer. From the Cave of Sant Gregori (Falset). Epipalaeolithic era (circa 9000 BC). Slate, engraving (slate, engraved with burin of flint) 7.1 x 3.6 x 0.9 cm. Museu de Reus © Photographic archive of Museu de Reus.

Figure. Second half of the 5th century BC. Wheel-thrown pottery. Museu del Cau Ferrat. Santiago Rusiñol Collection – Archaeology © Arxiu Fotogràfic del Consorci del Patrimoni de Sitges.

In this piece of clay that person deposited their desires and aspirations. We are probably looking at some kind of ex-voto that our ancestor used to request a favour of the gods.

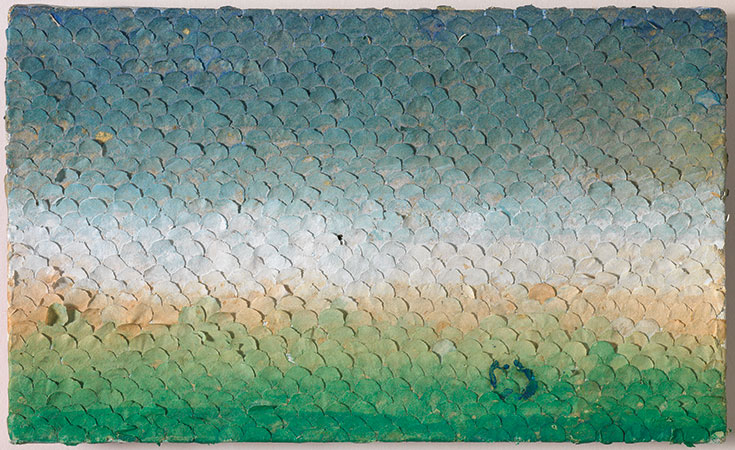

Perejaume: Landscape of Scales, Sant Iscle de Vallalta or Hortsavinyà, 1981. Collage of confetti and watercolour on canvas, 16 x 27 cm. Fundació Palau, Caldes d’Estrac. © Perejaume, VEGAP, Barcelona

.

Look

Anton Casamor d’Espona: Looking at the Sea, s/d. Sculpture in marble (figure) and granite (towel), 95 x 120 x 50 cm. Museu de l’Empordà.

per una trilogia: el mar, la sal i tu.

Llavors es fa el miracle i ve l’agost

-com va venir també l’estiu passat.

Enguany, però, la sorra se t’empassa

i és impossible fer com fan els altres:

no pots anar a cercar l’onada

i capbussar-te en l’alegria de la platja

ni vols per res del món negar que ara ja saps

que a més de sal, a l’aigua, hi suren cendres.

Tu no. Tu no vols oblidar-te de la mare.

The whole year of uncomfortable waiting

for a trilogy: the sea, the salt and you.

Then the miracle happens and August arrives

just like it came last summer.

This year, however, the sand swallows you up

and it is impossible to do as others do:

you can’t go looking for the wave

and immerse yourself in the joy of the beach

nor do you want for anything in the world to deny that you now know

that in addition to salt, ash floats in the water.

Not you. You don’t want to forget your mother.

Mireia Calafell, CENDRES (ASHES).

NOSALTRES, QUI. (WE WHO).

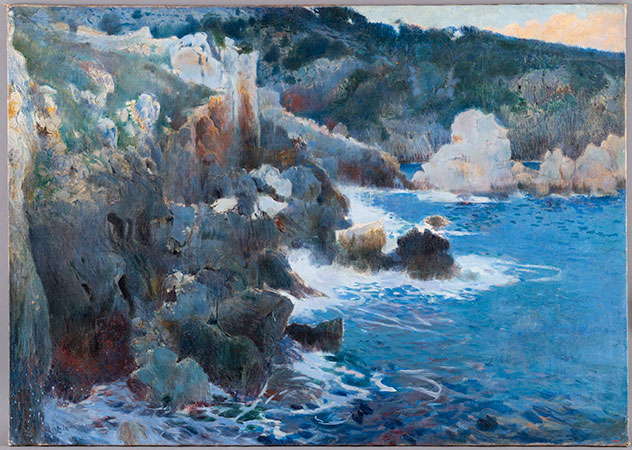

Joaquim Mir: Enchanted cove (Mallorca), circa 1901. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Santiago Rusiñol: “Malavida” of Sitges, ca. 1892-1893. Acquired from the Plandiura Collection, 1932. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Joan Rabascall: Platja de Sant Pere Pescador, 1981. Museu de l’Empordà. © Joan Rabascall, VEGAP, Barcelona.

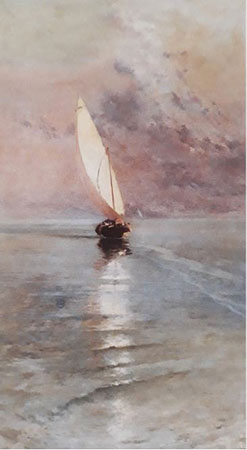

Baldomer Galofre: Marina, 1897. Oil painting on canvas, 2000 x 105 cm. Museu de Reus. © Museu de Reus

Ramon Martí i Alsina: Stormy Sea, between 1875 and 1884. Oil painting on canvas, 137 × 239 cm. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer.

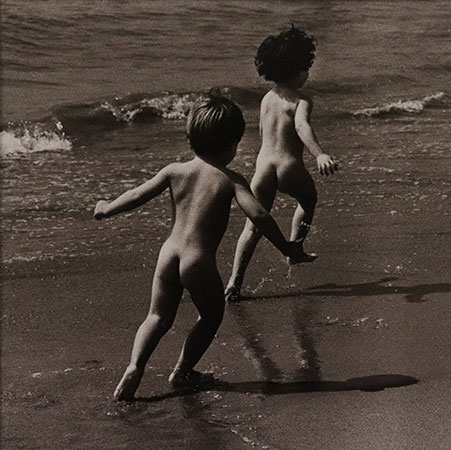

Luís Leandro Serrano: Nudes on the Beach, second half of the 20th century. Photograph, 27 x 27 cm. Museu de Manresa.

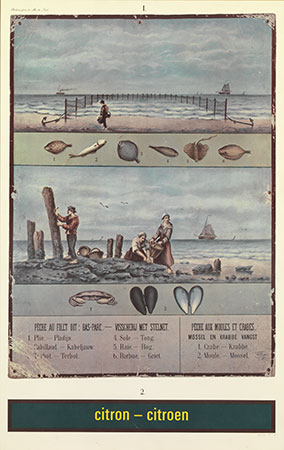

Marcel Broodthaers: Citron-Citroen (Réclame pour la Mer du Nord), 1974. Lithograph and screenprint on paper, 104.8 x 66.2 cm. MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. © Estate of Marcel Broodthaers, VEGAP, Barcelona.

Katsushika Hokusai: Under the Wave off Kanawaga, ca. 1832. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Former Drawings and Engravings Collection. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Master of Cabestany: Apparition of Jesus to his Disciples at Sea. (Relief of the portal of the Monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes, Girona). Second third of the 12th century. Carved and drilled marble, 81 x 62 x 18 cm. Museu Frederic Marès. © Photography: Guillem F-H.

* From the monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes, where this relief was originally located, you can see the sea.

Josep Icart Espallargas: Untitled, 1984. Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona. © Diputació de Tarragona. Museu d’Art Modern. Photographic archive. Alberich Fotògrafs

The point of view

roots, that drink from the heavens;

and in the soil, the deep roots of a beech tree

seem like silent peaks”

Francesc Català-Roca: Monument a Colom, 1950. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya © Arxiu històric del Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya/Fons Francesc Català-Roca

Ramon Casas i Carbó and Santiago Rusiñol i Prats: Portraying Each Other, summer 1890 in Sant Benet de Bages. Oil painting on canvas, 60 x 73cm. Museus de Sitges. © Arxiu Fotogràfic del Consorci del Patrimoni de Sitges.

The painting, however, offers us a third point of view, that of someone who was not there that day and who now observes it; in other words, us. To create this work, signed by both artists, first Casas painted the landscape while Rusiñol portrayed him, and then Rusiñol went to sit in the chair in the background, to paint his landscape, while Casas portrayed him. It is a painting with two signatures where each artist portrays the other. There are three canvases in the painting: one real and two painted. In total, there are three different points of view.

Lluís Borrassà, Young Man Leaning Out of the Window, ca. 1400-1415. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Acquired 1956. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Pablo Picasso: Salomé, París, summer-late 1905. Drypoint on copper stamped on Van Gelder vellum paper (third and definitive state), 40 x 34.8 cm. Fundació Palau, Caldes d’Estrac. © Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid.

Fina Miralles: Standard, 1976/2020. 2 photographs: 60 x 40 cm each. Projection of digitalised slides, inkjet printing on paper and sound recording. MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium. Donated by the artist. © Fina Miralles.

The look that looks at us

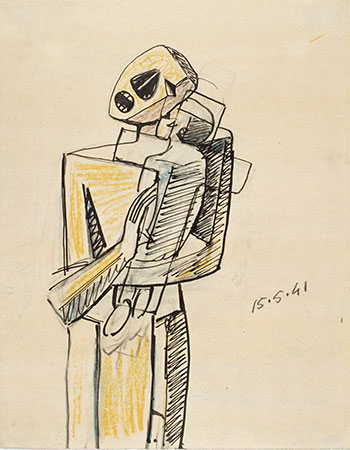

(1) Apel·les Fenosa and Pablo Picasso: Tête de Dora Maar, 1941. Museu Apel·les Fenosa. © Fenosa, VEGAP, Barcelona; Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid.

(2) Barbara Stammel: Sister I, 1997. Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona. © Diputació de Tarragona. Museu d’Art Modern. Arxiu Fotogràfic. Alberich Fotògrafs.

(3) Josep Tapiró: Bride, circa 1876-1896. Museu de Reus. © Museu de Reus.

The look of others

(and ours)

Of one I am certain, and the other threatens me.

the soul, returning to that divine love

that embraces us all on the cross.”

Michelangelo Buonarroti, 285.

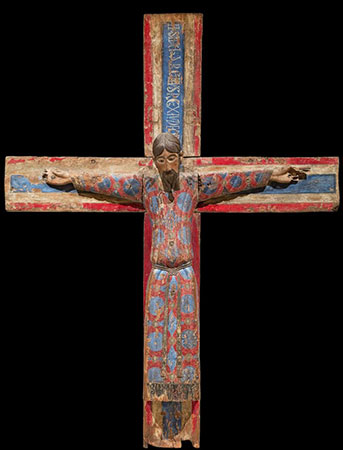

Anonymous, Christ from La Cerdanya, second half of the 12th century. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Former Museums Collection, 1972. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Anonymous, Majestat Batlló, mid-12th century. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Donated by Enric Batlló Batlló to the Barcelona Provincial Government; on loan, 1914. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Joaquim Llucià: Christ or Crucifixion, 1973. Acrylic on canvas, 200.5 x 199.5 cm. MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Donated by Carmen Buqueras. © Heirs of Joaquim Llucià.

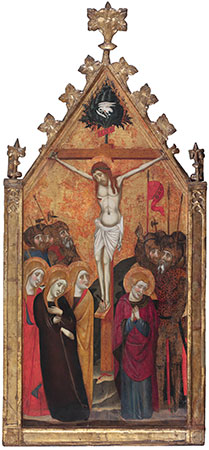

Jaume Serra, Calvary, ca. 1375-1385. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, On loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya. National Art Collection. Donated by Don Antonio Gallardo Ballart, 2015. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Juli González: Maternity of the Child on the Cross (Maternité a l’enfant à la croix), 1941. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Donated by Roberta González, daughter of the artist, 1972; entered the collection, 1973. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona; © Juli González, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Josep Berga i Boix: Calvary, 1889. Oil painting on canvas, 153 x 283 cm. Museu de la Garrotxa.

Attributed to Martín Bernat, Processional Cross with the Bust of Christ and the Instruments of the Passion, 1477-1505. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Contribution of the Provincial Commission of Historical and Artistic Monuments of Barcelona to the Provincial Museum of Antiquities of Barcelona, 1888. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Ramon Casas i Carbó: The Widow, 1889/90. Oil painting on canvas, 186 x 113 cm. Museu Víctor Balaguer. © Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer.

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (El Greco), Christ and the Cross, between 1590 and 1595. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Legacy of Santiago Espona, 1958. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Baldomer Gili Roig: District cross. Modern copy of the original glass negative, 13 x 18 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection.

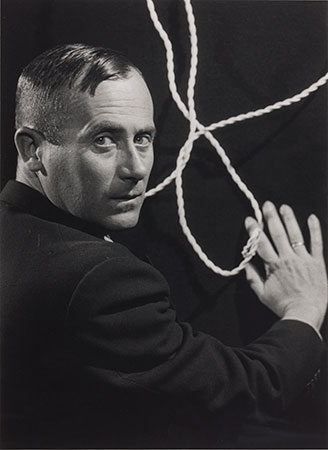

Man Ray: Miró, 1933 (?). Photograph in silver salts, 29 x 22.7 cm. MACBA Collection.

On loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Nacional Art Collection. © Man Ray, VEGAP, Barcelona