Curators: Pere Parramon and Laura Cornejo

Queer Aesthetics and Dissidences in the XMAC museums

Introduction. The who and the how

Affective, sexual and gender diversity is part of our nature. In the same way, art, as the most profoundly human expression possible, cannot fail to embody this wealth. Based on works from the collections of the Xarxa de Museus d’Art de Catalunya (XMAC), this exhibition celebrates the plurality of the ways of loving, desiring, feeling and thinking in aesthetic manifestations.

This 17th-century piece of furniture with Saints Cosmas and Damian serves as a metaphor to conceptualise the expression to “come out of the closet”, used to designate the act of making one’s same-gender relationship public. Taking advantage of the presence in the Catalan art collections of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender, intersex and queer people, or those with any other sexual orientation or gender identity –the acronym LGTBIQ+ encompasses them all– the exhibition itinerary identifies some of the ways in which they are evident or symbolise challenges to heteronormativity.

Each of the areas proposed in this exhibition invites us to contemplate with different eyes the pieces collected in the XMAC and to read the multiplicity of nuances within a multifaceted reality that is constantly being revised. Thus, the exhibition itinerary integrates the visibilities of the affective and identity diversity offered by the works themselves –represented according to the determining factors of their contexts– and, at the same time, the views that can be superimposed on them, those that are not limited to the mere perceptive act, but project onto it previous ideas and expectations.

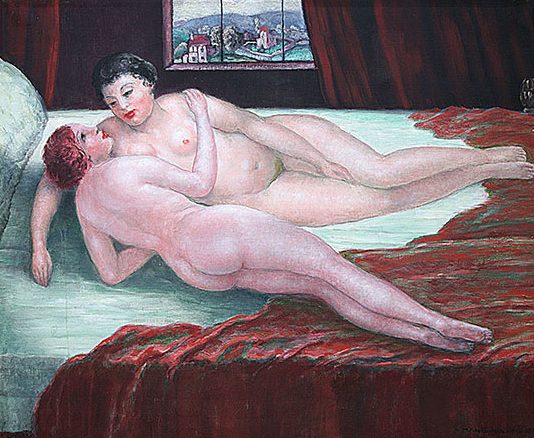

The exhibition We are who we are, we are what we are is presented as a reflection on queer subjectivity, queer being term in English that can be applied to sexual and gender dissidence with respect to traditional models. At the same time, it tells us of the treasure that is affection, such as the Dues dones esteses (Two women stretched out) (1944) by Joaquim Sunyer at the Fundació Palau (Caldes d’Estrac), and of what can be essential and primary in us (we think of Llena’s work) and as construction. Thus we observe Torrell’s collage.

Pharmacy Cabinet, 17th century. Wood carved and polychromed in oil, 179 x 127 x 22.5 cm. Provenance: Farmàcia Pallarès, Solsona. Museu Diocesà i Comarcal de Solsona. Inventory No. MDCS 985.

Toni Torrell. Untitled, no information. Collage, 36.5 x 30.5 cm. Museu de Valls. Donation of Ramon Civit.

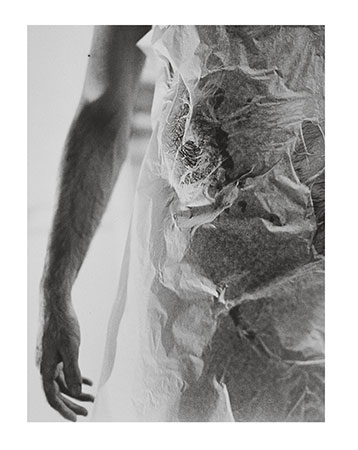

Antoni Llena. Painting made with sweat and semen, 1968 (2000). Photograph by Antoni Bernad in silver salts on photographic paper, 39.8 x 19.8 cm. MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Photo: Rocco Ricci. Courtesy of Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA). © Antoni Llena, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Expressions of dissidence

In recent decades we have begun to enrich the discourses regarding ourselves and our way of being and of being with others. In this assumption of diversity, we have introduced concepts such as biological sex, adding other possibilities to the traditional male-female binarism, including gender, sets of traits, roles and functions socially attributed to the sexes and sexual orientation, subjects towards which affinity and attraction are directed.

Combinations of body, behaviour and desire are, of course, infinite. From this point of view, dissent in gender expression constitutes one of the most obvious statements to others. From historical figures such as Anne Lister, a 19th-century British lesbian who in many ways lived and expressed as a man –the television series Gentleman Jack (created by Sally Wainwright, 2019-2022) was inspired by her diaries– to militant artists from the LGTBIQ+ collective, such as Cassils, who in performance finds a way to work on their body as a sculptural material through which to question conventional limits.

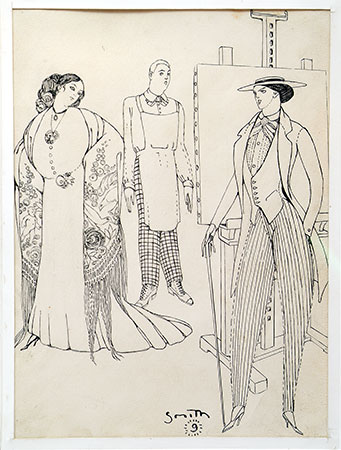

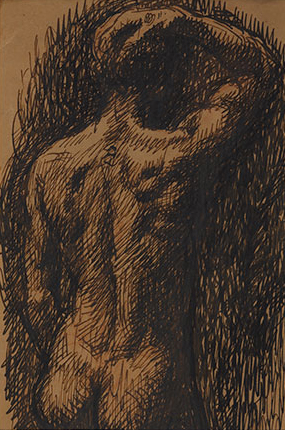

Ismael Smith. Figures, 1909. Ink on paper, 26 x 20 cm. Fundació Palau, Caldes d’Estrac; Registry no. 344.

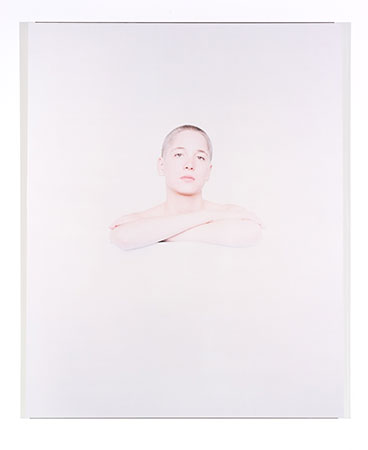

Neus Buira. Alice / Portrait VI, 1993. Colour photograph, 130 x 95 cm. MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida collection. Item present in the XMAC action Mirrors of Art. Infinite identities.

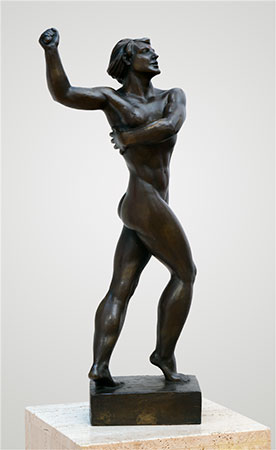

Santiago Costa Vaqué. The Tennis Player, no information. Bronze sculpture (lost wax casting), 58 x 21 x 13.5 cm. Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona; MAMT NIG 3075. Tarragona Provincial Government; Modern Art Museum; Photographic archive: Alberich Fotògrafs.

Ismael Smith. Salomé, 1910. Moulded plaster, 38 x 20.7 x 13.8 cm. Fons Maricel. Museu de Maricel, Sitges; Inventory no. FM 46.

Joan Morey. STP_La joie de vivre, 1999. DVD colour and audio stereo , 19’’. Museu de Granollers. MDG 12540.

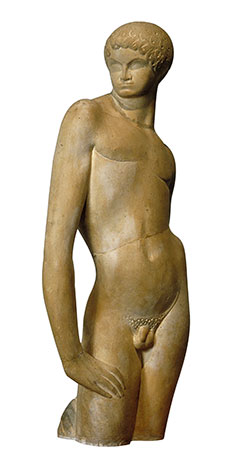

Strutting one’s stuff

In Spanish, an effeminate, “camp” man is often described as “showing a feather”. Although, like all gender expressions, this should not necessarily be understood as an image of one sexual orientation or another, it is often identified as an external sign of a gay man. The approximate equivalent in the case of a lesbian woman would be the stereotype of the “truck driver” or “dyke”. Depending on the time and the place, talk of the “feather” generates various reactions, ranging from mockery and derision to discrimination by homophobic groups, even within the LGTBIQ+ group itself. In dating apps, for example, it is easy to find those who are looking for men “without a feather” (i.e. not “camp”). Concurring in this aversion are both the denigration of femininity and the hatred of sexual and gender differences. In response, there are many voices and campaigns that revindicate the “feather” as an exercise of individual freedom and, in words of Jaime Gil de Biedma, a “ritual of collective complicity”, a proudly displayed “feather”, such as that portrayed by Gargallo, the one sculpted by Uró or the one photographed in 1958 by Joan Colom in El Raval (Les Tàpies) (Museu de Valls).

Pablo Gargallo. Young Male Nude, 1918. Stone carving, 58.7 x 27 x 15.5 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, donated by the Gargallo family, in memory of Francesc Gargallo, 1972. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Lluís Uró. Andalusian dancer (bailaor), first half of the 20th century. Sculpture, terracotta, 35 x 35 x 66 cm. Museu de Manresa.

Approaching the other side

“Trans-” is a prefix of Latin origin used to form adjectives with the meaning of “beyond” and to indicate the opposite position. Substantively, by “trans” we mean, like Gerard Coll-Planas in La voluntada i el desig (The Will and the Desire), a term “that encompasses all those whose sex does not correspond to their gender: transsexuals, transvestites, transgenders, etc.”. Each “beyond” is a story, figures as diverse as Andreu Sala – when praying to preserve her chastity, God made Princess Liberada grow a beard, who ended up being crucified by her father – and Ismael Smith, reproduced here, or the Transvestites of José Luis Cuevas (1981), preserved in the Girona Museum of Art collection, that, in their apparent undefinition, claim the right to any redefinition. For their part, the artists Helena Cabello and Ana Carceller delve into the story of the real case of Elena/Eleno de Céspedes, a 16th-century character who, despite being born a mulatto woman and a slave, lived as man. Finally, the trans photographer Mar C. Llop revindicates what is personal and political, doing so from the celebration of her own experiences.

Andreu Sala. Saint Wilgefortis, c. 1689. Sculpture in polychrome and gilded wood, 255 x 170 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, contribution of the Provincial Commission of Historical and Artistic Monuments of Barcelona to the Provincial Museum of Antiquities of Barcelona, 1879. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Ismael Smith. Figures with shawls, c. 1911. Ink and watercolour on paper, 33.7 x 26.5 cm. Donated by Enrique García-Herráiz in memory of Paco Smith. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola.

Cabello/Carceller. A/O (The Céspedes Case), July 2009 – July 2010. Single-channel video, colour, sound, 14 minutes, 39 seconds (work not on display). MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Courtesy of Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA). © Cabello/Carceller, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Ismael Smith. Figure (Eduard I’ll give you a boyfriend who’ll wear pants for me and a skirt for you), c. 1909. Pencil and ink on paper. Donated by Enrique García-Herráiz in memory of Paco Smith. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola.

Mar C. Llop. Identity Building, 2014. Print on aluminium, 85 x 144.5 cm. On loan from the artist’s heirs. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola.

How is desire represented?

Personal decisions, social expectations and discourses –political, ethnic, class, etc.– converge in identity, as well as elements related to sex, gender and sexual orientation. Certain physical or expressive features can contribute to the formation of an identity image, but with desire, unless the subject is represented in an attitude that signifies it (a way of looking, of seducing or consuming their desire), it is impossible to construct a specific appearance. For example, what does a bisexual person look like? And a gay? Naturally, there are as many appearances as there are people. Despite this, the need for symbolic references lead to conventions that are difficult to justify, if not entirely arbitrary. This is the case of the painting Naked Youth Sitting by the Sea (Hippolyte Flandrin, 1837) and its photographic emulation Caino (Wilhelm von Gloeden, c. 1902), both very close to Caba’s Academy. So entrenched in the collective imagination as a representation of homosexuality are they that Flandrin’s work ended up on the cover of No se lo digas a nadie (Don’t Tell Anyone) (Jaime Bayly), one of the most influential gay-themed novels of the 1990s. Why the association? Who knows?

Antoni Caba. Male Nude Academy, no date. Oil painting on canvas, 63.5 x 79 cm. Museu de l’Empordà, Figueres; ME 639. © mE. Museu Empordà, Figueres (Xavier Torner).

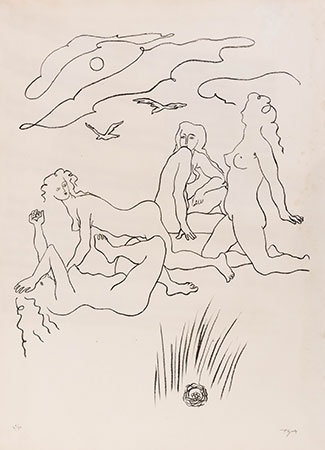

Particular friends

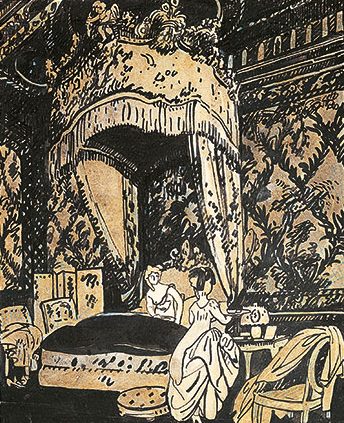

We can read into the historical and political reality a special reluctance to talk about dissident erotic practices among women and, over the centuries, these have tended to remain invisible. Desire between women has therefore often been represented under more or less subtle pretexts: the caresses of Diana’s entourage of nymphs, intimacy requested with an affectionate gesture, or the complicit embrace. The history of art has bequeathed us exceptional examples of the play between the insinuated, the seen and the lesbian. They include the paintings Gabrielle d’Estrées and the Duchess of Villars (1594) by the Fontainebleau School, Gustave Courbet’s The Dream (1886), Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Sofa (1893) and Lovis Corinth’s Group of Women (1904). However, love and seduction between women has been articulated to please a certain heteropatriarchal voyeurism, eager –as Julia Kristeva tells us in Powers of Perversion– to satisfy their curiosity about what women do when they are alone, whether in the domestic space –the instigator of “particular friendships” as in Aragay’s work– or in a moment of rest, as in Iturrino’s trio.

Josep de Togores. Nudes, 1928. Lithograph, 76 x 56 cm. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola. © Josep de Togores, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Group of Two Female Figures, early 2nd century AD. Carved in white marble, 69.5 x 71 x 42.5 cm. Provenance: Zaragoza. Museu Frederic Marès, Barcelona; Registry no. MFM 167. © Photo: Guillem F-H.

Manolo Hugué. Two young women from the back, 1929. Relief modelled and patinated in terracotta, 32.5 x 24.5 cm. Museu Abelló, Mollet del Vallès; Registry no. 2266.

Josep Aragay i Blanchar. Alcove Scene, 1915. Indian ink and watercolour on paper, 32.5 x 26.5 cm. Fundació Palau, Caldes d’Estrac; Registry no. 11.

Francisco Iturrino. The Women, c. 1905-1915. Oil painting on canvas, 100 x 110 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, legacy of Lluís Garriga Roig, 1940; entered the collection, 1942. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Construction of the lesbian identity

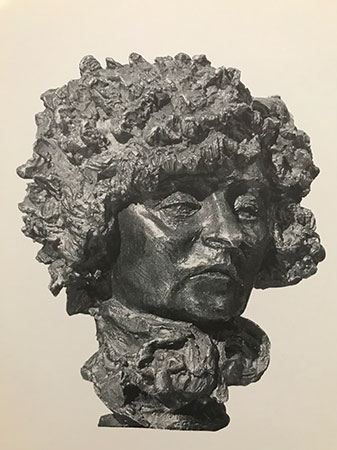

When we think of historical and cultural references to lesbian identity and of pioneers who have defended dissident sexual preferences, we cannot ignore the Greek poetess Sappho, who wrote about romantic relationships with her companions on the island of Lesbos, the origin of the term “lesbianism”. The Girona Art Museum has a portrait entitled Saphos (1979) signed by Modest Cuixart. In literature, Sappho normalised female homosexuality in the 4th century BC, as did the novelist Colette, the author of such books as Chéri and La Maison de Claudine, in the 20th century. An empowered woman, she experienced her affections freely, describing emotive images of female love, such as the attraction between Pidelaserra’s women, half embracing in a bed, and opening new queer spaces within the French society of the time. Many artists of the past defended inclinations other than the heterosexual, living with a partner of the same sex and subverting the natural destiny of women as producers of children dictated by the patriarchy; emblematic and familiar cases are those of the dancer Carmen Tórtola and the painter Marisa Roësset.

Jacques-Émile Blanche. Portrait of the Novelist Colette, c. 1905. Oil painting on canvas, 158 x 118 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, purchased at the Fifth International Exhibition of Fine Arts and Artistic Industries in Barcelona, 1907. © Photo: National Art Museum of Catalonia, Barcelona, 2023; © National Art Museum of Catalonia, Barcelona, 2023.

Apel·les Fenosa. Head of Colette, 1948. Clay, 19 x 15 x 16. Museu Apel·les Fenosa, el Vendrell. © Apel·les Fenosa, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Marià Pidelaserra i Brias. Nudes, 1937. Oil painting on canvas, 70 x 83 cm. Museu Abelló, Mollet del Vallès; Registry no. 2717.

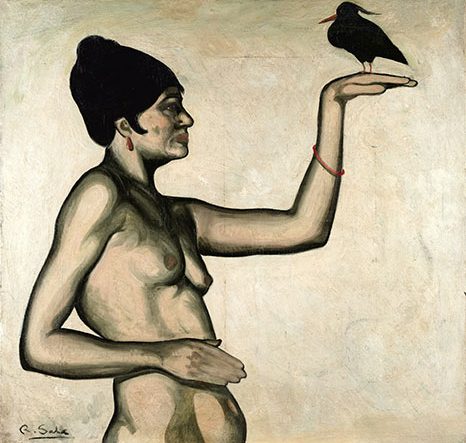

Rafael Sala Marco. Tórtola Valencia and the Crow, 1915. Oil painting on canvas, 84 x 86.7 cm. Biblioteca Museu Víctor Balaguer, Vilanova i la Geltrú; Registry no. 2490.

Marisa Roësset. Repose, 1928. Oil painting on canvas, 179 x 131 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, acquired at the Barcelona International Exhibition, 1929; entered the collection, 1931. Photo: National Art Museum of Catalonia, Barcelona, 2023; © the artist or her heirs.

Gays showing off

Regarding couples like the emperor Hadrian and the handsome Antinous –here depicted by Apel·les Fenosa– in the queer itinerary at the Museo del Prado The Look of the Other: Scenes for the Difference, Carlos G. Navarro and Álvaro Perdices point out both their “exceptional historical importance” and their “homosocial significance”. Always adapted to the conditions of each place and each era, presences such: the passionate (the gay artist Néstor portrays the flame of lovers who may well be two men); the courageous (Fenosa, a friend of the couple Jean Cocteau and Jean Marais, makes a small bust of the former so that the latter can take it to war); the inspiring (the couple Paco and Manolo defend the magic of real stories); and the optimistic (“I’m not afraid of the future”, sings Carles Congost’s protagonist having come out of the closet in the video Un mystique determinado (2003)) from the MORERA. Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Lleida, with their firm visibility pave the way for “we are who we are, we are how we are”.

Apel·les Fenosa. Antinous, 1949. Terracotta, 11.5 x 6 x 7 cm. Museu Apel·les Fenosa, el Vendrell. © Apel·les Fenosa, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Néstor. Possession, c. 1912-1913. Oil painting on canvas, 100 x 100 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Donated by Òscar Lena, 1958. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Apel·les Fenosa. Small Head of Jean Cocteau, 1939. Terracotta, 11.5 x 6 x 7 cm. Museu Apel·les Fenosa, el Vendrell. © Apel·les Fenosa, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Paco and Manolo. He is One, 2003. Print on aluminium, 50 x 70 cm. On loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya. National Photography Collection. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola.

Zeus goes cruising

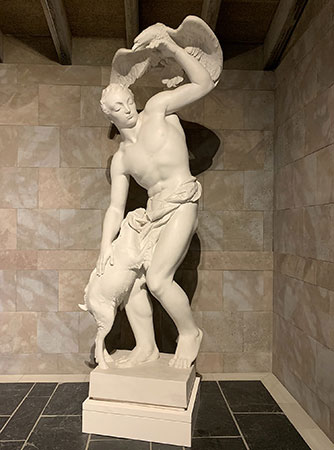

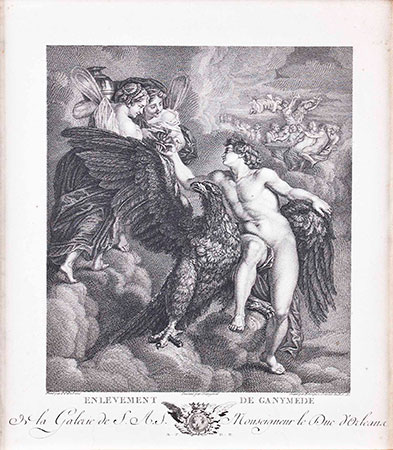

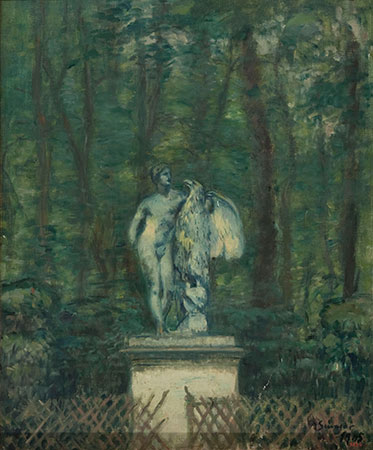

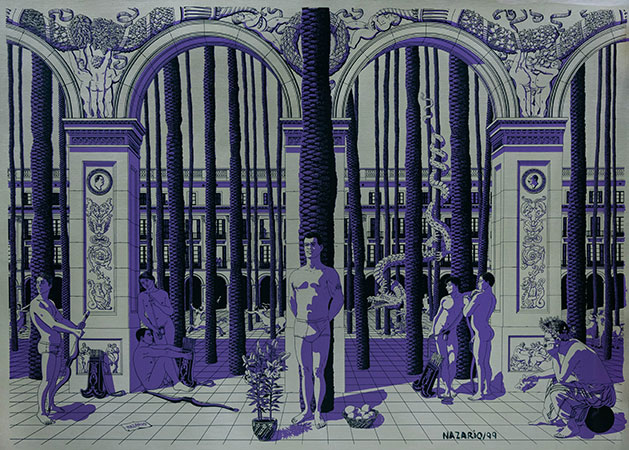

Throughout time, the seduction and abduction of the shepherd prince Ganymede by Zeus metamorphosed into an eagle has been a pretext for the representation of homosexual desire. Seen from a contemporary queer perspective, Joaquim Sunyer’s work –with a sculpture depicting the mythological episode in the middle of a leafy park– allows us to mention cruising. In other words, the search for clandestine sexual exchanges in more or less public spaces –evoked, by the way, in a hedonistic fantasy of Nazario’s– ranging from bucolic gardens and saunas with classical reminiscences, to sordid urinals, open fields and motorway rest areas. The film The Stranger of the Lake (directed by Alain Guiraudie, 2013) describes how it works and, above all, the regime of panoptic visibility that occurs there, while Alex Espinoza concludes his book Cruising: An Intimate History of a Radical Pastime by stating “We are doing something we know is illegal and subversive. The act itself is a protest, a revolt. People who cruise are outlaw rebels”.

Pablo Gargallo. The Shepherd of the Eagle, 1928. Moulded plaster, 268 x 97.5 x 54.5 cm. Museu de la Garrotxa, Olot; Inventory no. 659.

Benoît-Louis Henriquez. The abduction of Ganymede, according to Rubens, c. 1786. Burin, 25,4 x 22,1 cm. Gelonch-Viladegut fund. Museu de Lleida.

Joaquim Sunyer. French Garden with the Sculptural Group of Ganymede and the Eagle, 1905. Oil painting on canvas, 46 x 38 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, acquired from the Plandiura Collection, 1932. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023; © Joaquim Sunyer, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Nazario. Saint Sebastian and the centaurs (AIDS Allegory), 1999. Serigraph on canvas, 95 x 135 cm. Deposit of the Generalitat de Catalunya. National Collection. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola. © Nazario, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

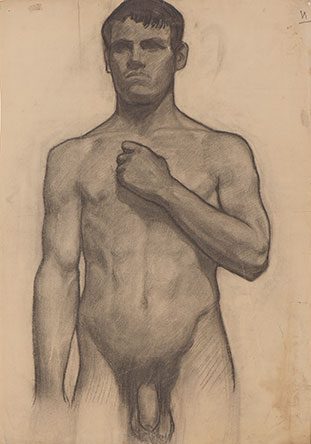

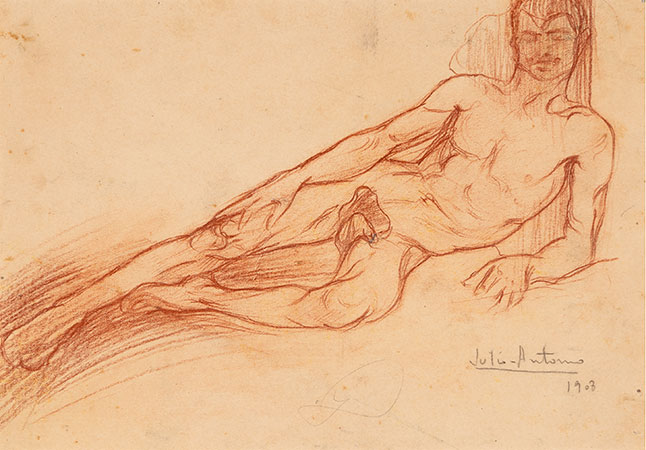

Academies for not very academic views

Academies often imposed modernity –natural nude studies– as part of the learning process and development of the artist’s skills. While in schools they were taught in groups, as seen with Rossend Nobas, professionals undertook them in their studies. This allowed a complicity –especially appreciable in Julio Antonio’s sanguine art– that could certainly stimulate the imagination of observers too used to not seeing the kind of intimacy between men they desired. In the same way, the homoerotic view could be satisfied in the final result of so many academies. In Kenneth Clark’s classic distinction between the “naked” and the “undressed” figure, the former, divine and heroic, does not require covering, while the latter, mortal and mundane, does. Although most academies had a “naked” vocation, in practice they could be appreciated as undressed, familiar and desirable bodies.

Antoni Estruch Bros. Academy, 1896. Pencil on paper, 36 x 24 cm. Provenance: legacy of Llorenç Lladó. Museu d’Art de Sabadell Collection, Sabadell City Council. Museu d’Art de Sabadell; Inventory no. 234.

Pablo Gargallo. Man from the Back, 1902-1903. Pen and ink on paper, 18.7 x 12.6 cm. Fundació Palau, Caldes d’Estrac; Registry no. 58.

Rossend Nobas. Academy, 1875. Watercolour on paper, 35 x 24.7 cm. Museu de l’Empordà, Figueres; ME 805. © mE. Museu Empordà, Figueres (Xavier Torner).

Julio Antonio (Julio Antonio Rodríguez Hernández). Male Nude, no date. Charcoal drawing on white paper, 61.5 x 42.5 cm. Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona; MAMT NIG 633. Tarragona Provincial Government; Museu d’Art Modern; Photographic archive; Alberich Fotògrafs.

Julio Antonio (Julio Antonio Rodríguez Hernández). Male Nude, 1908. Sanguine drawing on white paper, 22.3 x 32.5 cm. Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona; MAMT NIG 606. Tarragona Provincial Government; Museu d’Art Modern; Photographic archive; Alberich Fotògrafs.

The eroticised male body

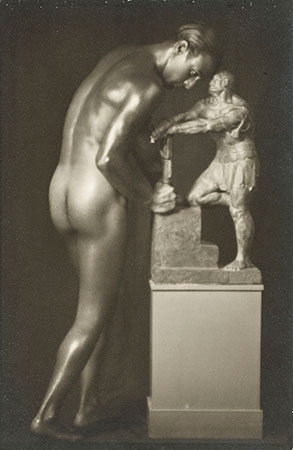

The artistic disciplines have shown how to compile the plurality of experiences, perceptions and representations of non-hegemonic masculinities in society and culture, despite the fact that depictions of gay masculinities have been belittled in the context of “masculinity”, a concept associated with the power structures derived from the legitimation of the patriarchy. In this respect, works such as those of Antoni Fabrés and Adolfo Wildt have succeeded in depicting a new “warrior” masculinity, represented through canons reserved for female eroticism: exoticism, inviting repose, the sensual contortion of the body, a fragmentary view of the genitals, etc. For its part, modern photography conferred a certain mysticism on homosexuality, with an exquisite treatment of the male nude in black and white, individualised in works such as those of Josep Masana and Joan Vilatobà. Very similar to de Wildt’s Croat, we have the close-up where sex is only hinted at in one of his works exhibited at the MNAC, in which the homoerotic implications in the representation of the bodies break with established social imaginaries. The Germans Wilhelm von Gloeden and Herbert List would be the most famous homosexual visual artists of the first half of the 20th century, with their photographs of young Sicilians or Greeks among references to classical antiquity. Nevertheless, in Catalonia, by the second half of the century, we also have a magnificent constructor of male homoerotic images in Toni Catany, represented, for example, by the Male Nude from the Somniar Déus series (1988) in the Valls Museum.

Josep Masana. Untitled (Nude study with sculpture), between 1920 and 1940. Photograph in gelatin and silver on baryta paper, 17.7 x 11.7 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, on loan from the Masana family, 1997. Photo: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2023; © the artist or his heirs.

Adolfo Wildt. The Croat, 1921. Plaster casting based on a stone sculpture, 72.5 x 52 x 56.5 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, purchased at the Barcelona International Exhibition, 1929; entered the collection, 1931, © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Saint Sebastian, a queer icon

Saint Sebastian was a Roman soldier condemned to death by torture for defending his faith. The saint’s body, with its sensual and ambiguous image, is a good example of how hagiography offers pretexts for dissident contemplations; those Saint Sebastian by Josep Tramulles and Joaquim Juncosa, the focus of so many gazes, and in the same vein, this one preserved in Vic or those of Andrea Bregno (Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya) and the Alejo de Vahía workshop (Museu Frederic Marès), becomes an ideal of beauty not greatly distanced from that described by Derek Jarman and Paul Humfress in the film Sebastiane (1976). Oscar Wilde and Tennessee Williams also praised the erotic sensations associated with this historical-literary character, and Yukio Mishima, in Confessions of a Mask (1949), wrote: “It is not the pain that emanates from his smooth chest, from his tense abdomen, from his slightly inclined hips, but a flame of melancholy pleasure, like that produced by music”. Seventeen years later, Mishima posed for the photographer Kishin Shinoyama, emulating the queer sexuality of Guido Reni’s Saint Sebastian (1615-1616).

Josep Tramulles. Altarpiece of Saint Sebastian, 1652-1654. Polychrome wood carving, 310 x 220 cm. Provenance: Hospital de Santa Caterina, Girona. Museu d’Art de Girona; Registry no. 251.709. Girona Provincial Government Collection.

Fra Joaquim Juncosa. The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, c. 1689. Oil on canvas, 198 x 139 cm. Institut Municipal dels Museus de Reus fund. Museu de Reus, MR 2072.

Medal with Saint Sebastian, Castella, 17th century. Gilt and chiselled bronze. MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval 4556. © MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval.

Coloured glasses

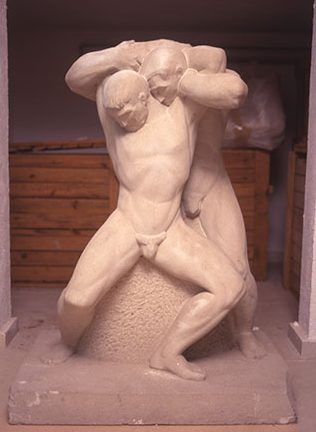

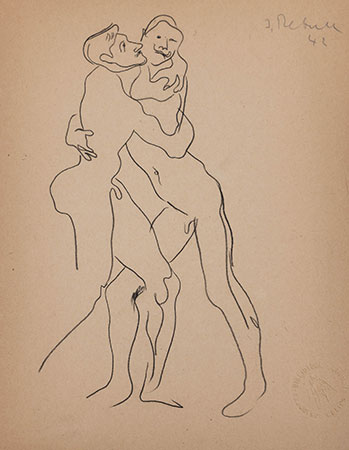

Neither the relationship between Blay’s driller and smelter –which is explained by what Carlos Reyero in Male Appearance and Identity identifies with manhood associated with work and a camaraderie free of sexual ambiguity– nor the life experience of the artist have anything to do with homosexual love. However, leaving aside Umberto Eco’s warnings about the dangers of overinterpreting or superimposing on the work something that is not there at all, the queer perspective defends, given the lack of visual references, that the members of a group such as gays can develop appropriationist re-readings. In fact, there are many images traditionally linked to a certain idea of masculinity –labourers, policemen, wrestlers, matadors, etc.– that become homoerotic icons in magazines such as Physique Pictorial; in the staging of music groups such as the Village People; or in the drawings of artists such as Tom de Finlàndia and Nazario. We can find an example of the last of these in the XMAC exhibition A Thousand Ways of Dying.

Miquel Blay. Driller and Smelter, 1903 (fragment from the Monument to Víctor Chávarri, Portugalete). Cast in bronze, 116 x 86 x 38 cm. Museu de la Garrotxa, Olot; Inventory no. 2511.

Rossend Nobas. Wounded bullfighter, 1871. Cast in bronze, 74.3 x 129.3 x 61.7 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, acquisition of the plaster cast, 1920; bronze casting donated by Lluís Masriera, 1921. © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2023.

Santiago Costa Vaqué. Graeco-Roman Wrestling, no date. Limestone sculpture, 112 x 82.5 x 55.5 cm. Museu d’Art Modern de Tarragona (work not on display); MAMT NIG 3074. Tarragona Provincial Government; Museu d’Art Modern; Photographic archive; Alberich Fotògrafs.

Rebull. Fighters, 1942. Graphite on paper, 26.8 x 29.9 cm. Donated by the Merino family. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola.

AIDS

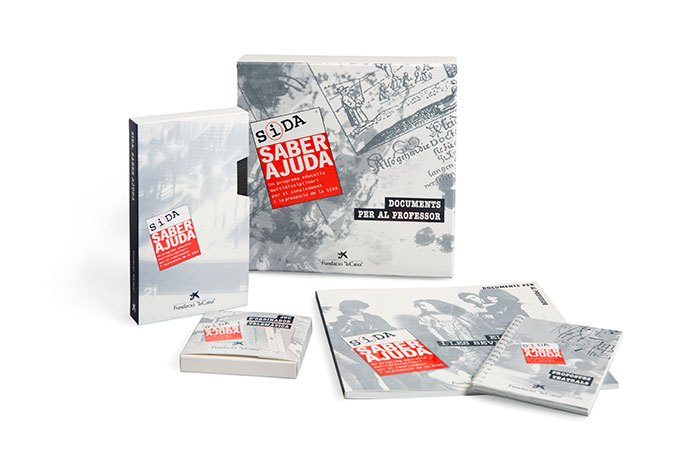

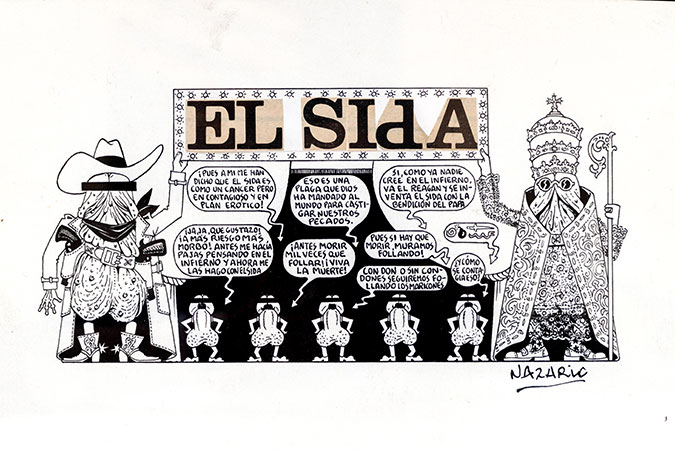

The emergence of AIDS in the 1980s was undoubtedly a fundamental episode when we talk about contemporary sexuality. In light of the homophobic stigma that surrounded the appearance of the virus, reviving the social persecution of “risk groups” such as homosexuals, Susan Sontag, among others, denounced this in the essay AIDS and its metaphors, and Nazario with scathing and openly critical comics; creators, photographers and writers stood up for the dignity of those affected by AIDS. In the most difficult moments of the contagion, and before the configuration of campaigns to promote knowledge and prevention of the disease, such as the educational programme AIDS. Knowing Helps, promoted by the La Caixa Foundation, different artists turned their physical agony not only into a document of the struggle against AIDS and gender discrimination, but also into the principal motif of their work. Convinced artistic expression can be an agent of change and social transformation, cases such as those of Pepe Espaliú, Derek Jarman and Keith Haring, the last of whom was the artist responsible for the mural Together we can stop AIDS in Barcelona’s Raval district and was an activist for sexual liberation; as well as with the depiction in a political key of their affections –as in the untitled piece (Ross & Harry) by Félix González Torres, starring Ross Laycock, his partner (also an AIDS victim) and the dog they shared.

Saura-Torrente, Edicions de l’Eixample (designers). AIDS Case. Knowing helps. A multidisciplinary educational programme for knowledge and the prevention of AIDS – Computer game. Telematics, 1994. Case with various materials, variable measures. Museu del Disseny de Barcelona; MDB 2650. Photograph: Xavi Padrós.

Nazario. AIDS, no date. Ink and collage on paper, 29.8 x 17.9 cm. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola. © Nazario, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2023.

Pink, let the love be there

Fortunately, the sexual and gender dissidences represented in art have also been integrated into the field of design, often using a provocative aesthetic that seeks to question or break with the dominant forces of history, experiences or acquired knowledge. With the revolution in postmodern architecture and design, there is a call for the subjectivity owed to Pop Art and the counterculture of the time, aimed at uprooting the foundations of a wise and affluent society. Examples such as the Shiva vase, designed by Ettore Sottsass and produced by BD Barcelona since then, testify to the fact that objects can generate a kind of ambiguity –a tension– when perceiving their conceptual limits and materials, raising a dissociation from what is socially accepted. This glazed ceramic vase, with its characteristic phallic profile, is a response to the priapic concept of hard, solid masculinity –according to cultural imperatives specific to the media and patriarchal ideology– by associating it with the iconic pink colour that has historically symbolised the convictions and struggles for diverse LGTBIQ+ identities.

Ettore Sottsass (designer) i BD Barcelona (production). Shiva, 1973 (2021). Vase, s/m. 23 x 17 x 7. Museu del Disseny de Barcelona; MDB 14048. Photograph: Estudio Rafael Vargas.

Epilogue: vindication, enjoyment and visibility

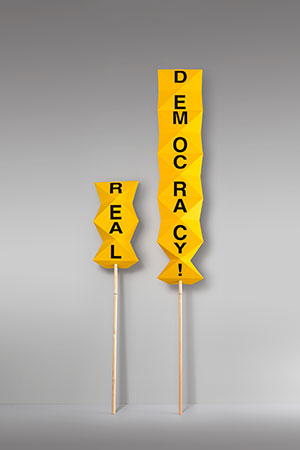

In The Division of the Sensitive, Jacques Rancière makes it clear that “politics and art, like knowledge, build ‘fictions’, i.e. material rearrangements of signs and images, of the relationships between what is done and what can be done”. That is why it is so important to pay attention to what artists and museums show us about ourselves, and also what they don’t. Because we have to continue to fight for freedom and diversity; isn’t that the foundation of a true democracy, such as that demanded by the piece Design for Protest? The reason is that we must continue to enjoy who we are and how we are –that is the invitation proffered by the sensual ornamented body of Ignasi Esteve– and also because we must continue to promote initiatives that give visibility to the wealth of a group that, ultimately, embraces us all: actions such as the realisation of the work by Randomagus, created ex professo for the XMAC on the occasion of LGTBIQ+ Liberation Day 2022.

UCH-CEU Product Design Master, Jorge Mora, Carmen Guijarro, Enrique Beneyto and Víctor Díez. Design for Protest, 2012. Banner, variable sizes. Museu del Disseny de Barcelona; MDB 15146. Photograph: Estudio Rafael Vargas.

Ignasi Esteve. Penjant, 1993. Print on fabric, 290 x 240 cm. Museu de Valls. Donation of the artist.

Randomagus. Untitled, 2022. Collage, 92 x 61.5 cm. Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola.