Medieval works in the Museums of the XMAC

Curator: Alberto Velasco Gonzàlez

The Middles Ages seem a long time ago to us. That’s why when we hear someone talking about the 13th century we feel a sense of vertigo, a kind of insecurity around the facts and the knowledge arising from the temporal distance. However, that’s not the only distance that determines our approach to the medieval centuries. How do we perceive the idea of physical distance in relation to the centuries of the Romanesque and Gothic styles? Can we really grasp what a long journey meant for the people of that time? Before the Covid-19 pandemic, we thought nothing of boarding a plane. Today, travelling to a far-off land is perhaps not as difficult as it was in the Middles Ages, but it still generates insecurity and uncertainty in us.

In the medieval centuries works of art also travelled accompanied by people. Their journeys involved the movement of objects, either because they were taken to be used during their sojourn far from home or —and this interests us more— because in their displacement from one place to another they became something rare and difficult to find in those distant markets. In this respect, faith and commerce were behind the arrival in the Catalan territories of many goods and artistic productions from such exotic places as Al-Andalus, Egypt, Persia or Byzantium, as well as from those nearer to home, such as Italy, France or the Southern Netherlands. Often, especially in the case of those arriving from the Orient or North Africa, objects that had no religious use in their places of origin became part of the sacred treasures of Catalan churches, often as relic holders. And that has an explanation, which we will attempt to provide with this exhibition.

Today, more than ever, the temporal distance of the centuries and a curiosity to learn how the long-distance journeys of people and objects were approached engender in us an attraction and, above all, a series of questions. This virtual exhibition will attempt to provide answers through different concepts and ideas. The intention is to speak about a series of works of art assembled in the museums that make up the Art Museums Network of Catalonia. They testify to the circulation of merchandise and objects in the Middles Ages and demonstrate that those movements brought about the arrival of a series of artistic productions, some of them quite exotic, that people found fascinating then and we still marvel at today.

From east to west, via al-andalus

In a time of 5G, globalisation and Amazon, we need to ask ourselves why, at a 1500-year-old archaeological site in the Segrià region we find a set of objects of Mediterranean and oriental origin. Likewise, it could seem surprising to us that chess pieces made in Egypt or Persia would have been bought by an 11th-century knight and his wife and would end up as part of the treasure of the abbacy of Sant Pere d’Àger. They all have their own particular explanation, but there is something many have in common. It is that the relations between East and West have thrived since time immemorial and that this is reflected in the exchange of artistic objects and products. Catalan merchants have had consulates in Tunisia, Béjaïa (Algeria) and Alexandria since the 13th century. However, the movement was not just one way. For example, woven wool from Lleida reached beyond the farthest confines of Christianity and in Saint Catherine’s Monastery on the Sinai Peninsula (Egypt) there is a painting donated in 1387 by Bernat Maresa, a citizen of Barcelona and the Catalan consul in Damascus. Mediterranean relations and trade with Al-Andalus facilitated the arrival of textiles and other luxury items that fascinated the Christian elites, as well as more modest works, such as the Byzantine icons that were acquired by the oligarchs of towns and cities. In this respect, we know that in 1404 several vessels arrived in the port of Barcelona with numerous icons from Byzantium among their cargos, as well as chairs, chests, carpets and other objects.

Near Eastern, North African or southern Italian workshop Censer, 6th century. Cast bronze, 21.5 x 13.5 x 12 cm. From the basilica of El Bovalar (Seròs). Lleida Diocesan and County Museum.

Egyptian, Iranian or Iraqi workshop. Chess pieces, 8th-9th centuries. Carved rock crystal (different sizes). From the abbacy of Sant Pere d’Àger (Lleida). Lleida Diocesan and County Museum.

Europe, a large

In the medieval centuries certain artistic productions spread en masse across Europe thanks to the trading networks. Romanesque-period precious metal work in Catalonia was responsible for important local productions, but it was also when a large quantity of low-cost but very attractive objets d’art, such as the Limoges enamels. began to be imported. The Limoges region produced crosses, reliquaries, candelabra, pyxides, ciboria, censers, book covers and croziers. The arrival of these articles in Catalonia even led to imitations being made by local workshops. It was during the Gothic period that we see the triumph of certain artistic productions with designation of origin. English embroidery, els French ivory, Nottingham alabaster, Italian chests, Flemish altarpieces and brass and copper metalwork from towns such as Nuremberg or regions such as Namur flooded the European market. At that time Flanders excelled as a grand market, which is why one of the first Catalan consulates was opened in Bruges in 1330. Thus, the powerful trading networks woven between Flanders and the Crown of Aragon allowed objects such as the exceptional brass lamp preserved in the Solsona Diocesan and County Museum to reach Santa Fe de Valldeperes.

Limoges workshop. Ciborium from La Cerdanya, early 13th century. Gilded copper with champlevé enamel applications, 13.1 x 15.2 x 14 cm. From an undetermined church in the La Cerdanya region. National Art Museum of Catalonia.

The Mongol empire (textile) and England (embroidery). Chasuble from the vestments of Saint Vincent, second half of the 13th century (textile) and circa 1340-1360 (embroidery). Silk and gold lampas with opus anglicanum embroidery, silk and metal passementerie, 133 x 72 cm. From La Seu Vella de Lleida (previously in Sant Vicenç de Roda de Isàvena, Huesca). Barcelona Museum of Design.

Flemish workshop. “Arnolfini”-type lamp, mitjan segle XV. Llautó cisellat, 44 x 55 cm. Provinent de Santa Fe de Valldeperes (Navàs). Museu Diocesà i Comarcal de Solsona

Northern Italian workshop. Small chest, 15th century. Gesso pastiglia moulded and polychromed on a wooden frame, 11 x 15.9 x 10.6 cm. Barcelona Museum of Design.

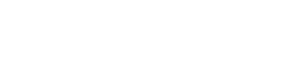

Workshop in the Brabant region. Altarpiece-tabernacle, circa 1500. Sculpture in polychromed wood and painting on board, 145 x 100 cm. From the monastery of Santa Clara de Calabazanos (Palencia). Frederic Marès Museum, Barcelona.

The altarpiece-tabernacle from the monastery of Santa Clara de Calabazanos is an atypical work in Castile in terms of its structural typology. Although altarpieces-tabernacles had been known in Castile from the 13th century, the typology of the one we are analysing here is more in keeping with the Flemish models, together with the style of the sculpture that presides over it, which was probably carved in the Brabant area (Brussels or Antwerp). The Gothic centuries brought to the Spanish kingdoms numerous pictorial sculpted altarpieces from the Southern Netherlands, where there was a thriving network of workshops that exported their creations all over Europe. In Catalonia we know those of the monastery of Pedralbes or that of the Franciscan monastery in Figueres. Many of them arrived at the hands of private individuals with trading connections to Flanders or with a preference for northern art.

The embellishment of altars and homes

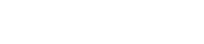

Images played an important role in both churches and homes. The religious experience was channelled through the altarpieces that presided over the church altars, as well as through the smaller devotional paintings and sculptures used by the faithful in the intimacy of their homes. To satisfy the requirement for works of art in those areas it was possible to turn to local artists, or imported productions that were able to contribute exotism, distinction and perhaps even greater emotionality to the practice of piety. Some of the works in this section speak to us of the vitality of the trade in works of art between the Crown of Aragon and northern Europe as early as the beginning of the 15th century. Others, in contrast, demonstrate it through the production and export of carved altarpieces that would become centralised in the Brabant area, with numerous examples documented in Spanish territory. Certain productions, such as the small sculptures from Mechelen, were specially designed for use in the home, although when they reached Spain, many became part of church or monastery altars. The same thing occurred with the small French ivories or the Flemish pieces made in terracotta, the arrival of which is well attested in Barcelona in the mercantile documentation and the inventories of private houses.

Anonymous French artist, Our Lady and Angels with Candles, early 14th century. Carved ivory, 18.8 x 6 x 2.5 cm (Our Lady), 14.8 x 2.5 x 1.5 cm (angel on left), 14.8 x 3 x 1.5 cm (angel on right). From the chapel of Santa Maria de Savila (Ceuró, Castellar de la Ribera). Solsona Diocesan and County Museum.

Anonymous Flemish artist. Wise Men of the Epiphany, circa 1400. Sculpture in polychromed wood, 45.5 x 17 x 9.4 cm // 46.7 x 18 x 11 cm. From the cathedral of Sant Pere, Jaca (Huesca). Cau Ferrat Museum, Sitges.

Parisian workshop, Saint George, circa 1420-1450. Cast, forged and engraved silver, gilded and polychromed, 54 x 24 x 24 cm. From the chapel of Sant Jordi in the Palau del la Generalitat de Catalunya. National Art Museum of Catalonia.

Relics and adaptations

Seen through 21st-century eyes, it could seem strange to us that inside a Christian altar consecrated in the 11th century there were relics wrapped in fabric from the Orient inside a receptacle from al-Andalus. How could it be that the mortal remains of saints —of Christian martyrs— were protected by items manufactured by non-believers? The answer is simple: the fascination of Christian society for objects of art produced by “the others”. This meant that many of the relic holders used in Catalonia in the Romanesque period, the so-called lipsanothecas, were of oriental or Andalusian origin. The Caliphate of Cordoba (929-1031) had a thriving market in luxury goods that favoured the arrival of, for example, cut-glass flasks made in Persia and designed to contain cosmetics. Despite such a prosaic original purpose, some of these pieces would end up being used to consecrate altars in Catalonia. A similar case would be the Hispano-Arabic textiles made with silk that were sometimes used to make liturgical garments or to protect the relics kept in lipsanothecas, as they were considered to be noble materials and worthy of protecting holy remains. In the Gothic centuries, chests lined with different materials, such as those of pewter from Cyprus, or those of bone from Italy made by the Embriachi family, went from containing prized objects from the profane world to hosting the mortal remains of saints in churches and cathedrals.

Iranian workshop. Small bottle, 9th-10th centuries. Blown and cut glass, 6 x 6 cm. From the church of Sant Pere de Montgrony. MEV, Museu d’Art Medieval.

Iranian or Egyptian workshop. Molar flask, 9th-10th centuries. Glass blown with a mould and cut, 7.6 x 2 x 2 cm. From Sant Quirze de Pedret. Solsona Diocesan and County Museum.

Hispano-Arabic or Maghribi workshop. Bowl, 10th century. Blown and cut glass, 11.2 cm (height) x 13.1 (diameter). From the church of Sant Vicenç de Besalú. Girona Museum of Art.

Hispano-Arabic workshops, Central Asia and Lucca. Dalmatic from the “Tern” of Saint Valerius, 13th-14th centuries. Silk and other materials, 145 x 145 cm. From La Seu Vella de Lleida (previously in Sant Vicenç de Roda de Isàvena). Museum of Design.

Cypriot workshop. Small chest, circa 1300. Pewter sheets on a wooden frame, 5.2 x 10.3 x 7.5 cm. From the monastery of Santa María de Nogales (León). National Art Museum of Catalonia.

The island of Cyprus became a strategic enclave on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, the crusades and the route to the Orient. This made it an essential stop for travellers on one of these journeys. On the island they would have found a dynamic market where they could purchase opulent textiles or chests such as this, known as “Cyprus chests”. They had an unusual appearance due to the sheets of pewter (an alloy of lead and tin) that covered the wooden frame and often repeated the same motifs. We can find examples in Maastricht, Florence, Leipzig and Paris. In this last case, the Musée de Cluny has two detached plaques from a small chest of this type on which we can read “I am the small chest that came from Cyprus to be sold; blessed be all those who buy me”. In Spain we know of various examples in Castile, while in Catalonia we have the two from the Treasury of the Cathedral of Girona and the one found in 1921 in the tomb of the Mercedarian sant Pere Ermengol (1238-1304) in the church of La Guàrdia de Prats and now in the Tarragona Diocesan Museum. Pere Ermengol devoted the latter part of his life to liberating Christian captives from Granada, Murcia and Algiers.

Imported for liturgy and devotion

The first documental evidence of Limousin enamelwork in Catalan churches dates from the early 13th century. This craftwork from Limoges received an important boost as a result of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) and the support of Pope Innocent III (1298-1216), who would have seen it on a visit to that region. The visual brilliance of the enamels that decorated the pieces and their relatively low cost were two of the reasons for their success. The practices associated with the liturgy led to the arrival of other objects needed for the rituals and the embellishment of the altars, such as the bronze images of Christ manufactured in the Germanic area, which excelled in high quality metalwork. Also of note are the bowls or basins erroneously known as “Hanseatic”. Most of these have been found in Estonia, although the area in which they were distributed stretches from the Baltic to the lower Rhine and includes England, Poland and the North Sea coast. This democratisation of objects linked to the faith is also manifested in the French ivories that, although they were made with a precious material, were small and relatively cheap.

Anonymous Germanic artist. Christ, second half of the 12th century. Cast and gilded bronze, 19.4 x 19 x 3.4 cm. From Santa Maria de Mur (formerly the church of Sant Miquel de Moror). National Art Museum of Catalonia.

French workshop (Paris). Pax, 14th century (ivory plaque) and 15th century (silver frame). Gilded ivory and silver, 21.2 x 7.7 x 2.7 cm. From Sant Cebrián de Campos (Palencia). Frederic Marès Museum, Barcelona.

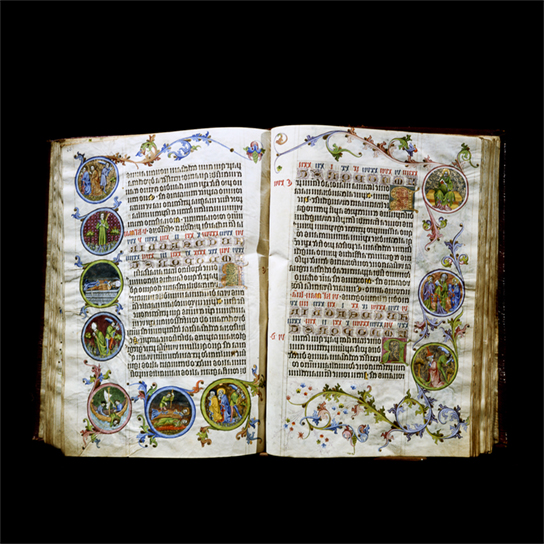

Bohemian workshop. Martyrology of Usuard, circa 1254 (text) and circa 1450 (miniatures). Parchment, 469 x 338 mm. Girona Museum of Art.